The Cuban Missile Crisis 1962

"We’re eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow just blinked." —Dean Rusk

President Kennedy was at heart a Cold Warrior. He had been critical of the Eisenhower administration’s foreign policy and was prepared to take a hard line with communism. Upon returning from his Vienna meeting with Khrushchev in 1961, he acknowledged that his Soviet counterpart “beat the hell out of me.” He vowed to get tough with the Soviets in order to demonstrate that he (and the U.S.) could not be pushed around. He decided that the time was suitable for a stand, and that Vietnam would be the place. Thus he began the buildup of the American advisory cadre in Vietnam that was to lead to America’s much greater involvement during the Johnson years. (See Vietnam section.)

A greater threat than Vietnam soon emerged, however. The United States had continued to keep a close eye on Cuba following the Bay of Pigs, using spy planes to fly over the island and photograph any suspected military activity. Then, in October 1962, American reconnaissance flights revealed that the Soviets  were building nuclear weapons bases in Cuba, a violation of the Monroe Doctrine and a serious threat to American security. Additional aerial reconnaissance photos confirmed that preparations were underway to install missile launchers on the island of Cuba with the potential to launch nuclear tipped weapons at the U.S.

were building nuclear weapons bases in Cuba, a violation of the Monroe Doctrine and a serious threat to American security. Additional aerial reconnaissance photos confirmed that preparations were underway to install missile launchers on the island of Cuba with the potential to launch nuclear tipped weapons at the U.S.

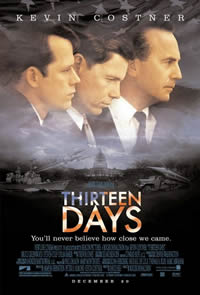

The Cuban missile crisis was the closest the world ever came to all-out nuclear war. Following the first sightings of the missiles being placed by Soviets, additional Russian vessels were seen heading towards Cuba carrying more missile components. Thus began what became known as “the 13 days,” a period of extremely high tension in which the Kennedy administration tried to find a way to get the missiles out of Cuba without starting World War III. Kennedy and his advisers had to walk a very tight line in order to achieve that end.

Robert Kennedy's book, Thirteen Days, is a detailed analysis of the missile crisis. Robert F. Kennedy was JFK's brother, Attorney General and closest adviser. President Kennedy had to confront not only Khrushchev and his plan to turn Cuba into a missile base for the Soviets; he also had to deal with his military leaders, who were generally in favor of bold, aggressive action. In order to foster a full discussion of all possible options, the president convened an Executive Committee of the National Security Council, known as EXCOMM, consisting of top military and civilian advisors, including the president’s brother. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and some civilians supported the bombing of missile sites in Cuba followed up by an all-out military invasion. Less aggressive options were also heatedly discussed.

As the EXCOMM huddled in Washington trying to work out a plan to deal with the situation, Marines and army units were placed on high alert and began preparation for an invasion of Cuba. The American naval base at Guantánamo Bay was braced for action, and Marines were flown from the First Marine Division site in Camp Pendleton, California, to the East Coast to be positioned for further action. The 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions were also placed on high alert. As military preparations went on, Kennedy struggled to keep the media from over-reporting the situation and causing panic in the streets. He also addressed the nation directly via television.

Continued flights by U-2 spy planes tracked the progress of the installations, and low-level flights were authorized to get a close-up view of the missile sites. As tensions mounted, the debate extended to the United Nations, where Ambassador Adlai Stevenson confronted the Soviet ambassador with pictures of the  missile installations (left). Stevenson demonstrated for the world that America’s claims were not lies, as the Soviet minister had charged. The United States Navy placed what was called a “quarantine” around the island of Cuba (the term blockade was not used since it is a term indicating that a state of war exists), and Soviet ships were ordered not to advance any farther with their missile cargos.

missile installations (left). Stevenson demonstrated for the world that America’s claims were not lies, as the Soviet minister had charged. The United States Navy placed what was called a “quarantine” around the island of Cuba (the term blockade was not used since it is a term indicating that a state of war exists), and Soviet ships were ordered not to advance any farther with their missile cargos.

As tension mounted, Soviet Premier Khrushchev sent a message offering a means to end the standoff through negotiation. Careful analysis of the message revealed that it was drafted personally by Khrushchev, who was obviously under considerable stress. The following day a much harsher message was received, apparently the result of internal bickering in the Kremlin. The president decided to respond to Khrushchev’s first message, ignoring the more threatening follow up. By using means of communication outside normal diplomatic channels and tense negotiations between Robert Kennedy and the Soviet ambassador in Washington, the Americans were able to convince the Soviets to cease development of the missile sites.

The deal that was finally struck involved a concession by the United States that some obsolete missiles in Turkey would eventually be removed (supposedly they were going to be removed anyway.) In addition the United States promised not to invade Cuba. When the crisis was over, the world breathed a little easier, and the most frightening moments of the Cold War had passed. Tensions remained; the confrontation had shaken the world. As Secretary of State Dean Rusk later put it, "We''re eyeball to eyeball and the I think the other fellow blinked." Not long afterward a “hot line” was established between Washington and Moscow to facilitate communications in case of a future crisis.

See Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: Norton, 1973) and the film of the same name based on the book starring Bruce Greenwood and Kevin Costner. See also Graham Allison, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (2nd ed. New York: Longman, 1999.)

More recent scholarship has called into question the accuracy of some of the assertions made in Robery Kennedy's book. Disagreements persist, but it is clear that the crisis was real; the situation between the two nuclear superpowers was fraught with danger. A misstep on either said might have led to a disastrous encounter.

To illustrate how serious it was, here are words from a recently translated Soviet document from the period.

Premier Khrushchev is quoted as saying:

The matter is that we do not want to unleash a war, we only wanted to threaten them, to restrain the USA with regards to Cuba.

The difficulty is that we didn’t concentrate everything that we had planned to and did not publish the agreement.

The tragic aspect is that they might attack and we will repulse it. It might turn into a big war.

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed, and the world wa spared a military confrontation with nuclear weapons.

Sage American History | Cold War Part 1 | Cold war Part 2 | Updated February 4, 2018