America and the Cold War: The Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy Years

Copyright © 2012, 2017 Henry J. Sage

|

|

|

General. The history of warfare in the modern world is notable for the fact that two of the most terrible wars of all time were fought in the first half of the 20th century. What probably would have been the most destructive war ever fought, which we would probably designate as World War III—if there were any “we” around to make note of it—was never fought. Instead what we got was the Cold War, often referred to as the “balance of terror.”

That standoff between the two great superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, and their allies, probably occurred because for the first time in history all sides could readily understand the huge price they would pay by precipitating an all-out conflict. Because of the use of the two atomic bombs in World War II on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, evidence existed to show how horrible a full-blown nuclear exchange would be. By the mid-1950s both sides had constructed bombs which were thousands of times more powerful than the first two dropped in 1945; in a nuclear exchange, there might well be no winners.

The idea of a state of international tension was certainly not a new development that emerged in the middle of the 20th century. Following the Napoleonic wars, the European powers assembled in 1815 in Vienna under the leadership of Austrian Prince Metternich and created a structure designed to prevent the further outbreak of the kind that had torn Europe for more than two decades. The tension was there, but it was alleviated by the unwillingness of the great powers to trigger a conflict. The alliance system based upon some sort of balance of power was continued under the leadership of Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck at the Congress of Berlin of 1878. Once again, great tensions existed, but that system held those powers in check.

When the breakdown finally did occur in 1914, it was because of a long series of diplomatic blunders driven by the shortsightedness of rulers who lacked the vision either of Metternich or Bismarck. The Great War of 1914-1918, probably the most terrible war ever fought by armies on the ground, was barely over before the tensions were reignited. World War II began chiefly because of the destructive nature of the so-called peace treaty written at Versailles by the victors. Although antiwar movements prospered in the 1920s and early 1930s, the growing militarism of Italy, Germany and Japan revived the kind of international discomfort that had preceded the First World War. That militarism led to the outbreak of another war in 1939. In some ways, World War II was a continuation of World War I.

Thus long periods of international tension were nothing new; the difference is that after 1945, weapons technology had proceeded so far that all but the most obtuse political players could see that the future of full-scale, no-holds-barred warfare had grown too terrible to contemplate. Ironically, then, the greatest deterrent to war in the nuclear age became war itself.

The Cold War kept the world on edge for over 50 years. The best that can be said of it is that it never erupted into the holocaust many feared. For a time, during the 1950s, the question of a ‘Third World War’ was less a matter of “if” than of “when?” People built bomb shelters in their back yards and school children practiced a-bomb drills. Nuclear war seemed inevitable. Under that shadow of a potential holocaust, the NATO and Warsaw Pact (or Eastern Bloc) nations twisted and turned to advance their goals while avoiding the spark that might instigate a war of surpassing destruction. Most internationally significant events of that period—from trouble in the Middle East, to wars of national liberation, to issues of developing nations in Africa and Latin America—were played out against the backdrop of the Cold War.

The Cold War had many ramifications for the American people. The anti-Communist witch hunts of the 1940s and 1950s led to severe consequences for many Americans based solely on their political views. The campaign of Senator Joseph McCarthy to root out real or imagined communist agents in the U.S. government gave America the term McCarthyism, a synonym for political intolerance. The Korean and Vietnam wars put American lives on the line on the fight against Communism. Most of all, the fear of nuclear war made life unsettling for people even in a time of supposed peace. The collapse of the Soviet Union ended the Cold War, but the remnants of that age—the thousands of nuclear warheads still in existence and in the possession of a number of nations—are still with us.

See The Legacy of World War II

The Truman Years

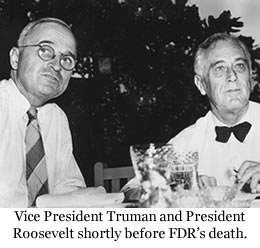

Harry S. Truman was a modest man. (His critics at the time might have said, “And with good reason,” though his stature as a president has grown considerably in recent years.) Raised in Independence, Missouri, Harry Truman worked at various job after graduation from high school in 1901. When the United States entered World War I, Captain Truman commanded an artillery battery and saw significant action in France. Following the failure of a store he ran during the 1922 depression, Truman entered politics, holding various positions under the eye of Missouri party boss Tom Pendergast. In 1934 Truman was elected to the United States Senate, where he served until he was tapped by Franklin Roosevelt to run with him as vice presidential candidate in 1944.

When President Roosevelt urged Senator Truman to join him on the ticket, Truman balked. As a Senate committee chairman overseeing military procurement during World War II, he had taken on powerful industry leaders and accused them of profiteering and shoddy practices, even as young Americans were dying on the battlefield. Because of that fact, and because he was a loyal New Deal Democrat, Roosevelt wanted him on the ticket. (After Truman became President, General Marshall claimed that Truman’s work in the Senate “Was worth Two divisions to me.”)

Bess Truman didn’t like Washington at all and couldn’t imagine her husband being in the White House. But Roosevelt would not take no for an answer, so the reluctant senator from Missouri became vice president and soon thereafter was elevated to an office which he never sought and did not really want. Harry Truman was the last American without a college education to be elected president (he was reelected in his own right in 1948), but that is not to say he was not well-educated. He read widely, especially in history, and was nobody's fool. Despite all that, he was nevertheless ill-prepared to take over the most powerful office in the free world. Few if any men could have adequately replaced FDR.

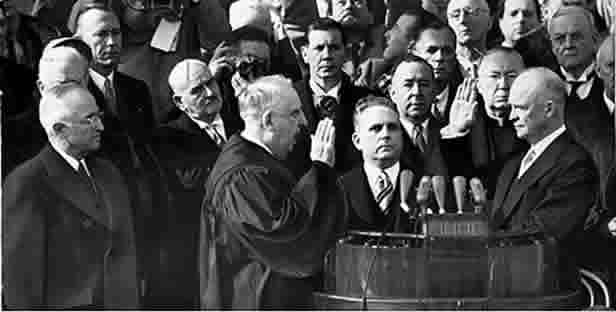

Harry S Truman being sworn in as Bess Truman and FDR’s cabinet look on, April 12, 1945

After informing the Vice President of her husband’s death,

Eleanor Roosevelt said to the new President, “What can

we

do for you, Harry? For you are the one in trouble now.”

Franklin Roosevelt had been president for over 12 years when he died. Schoolchildren who mourned his death had not been born when FDR was sworn in on March 4, 1933. No one will ever know how conscious Franklin Roosevelt was of his own mortality, but historians have speculated that he probably experienced a sense of denial regarding his health, coupled with a determination to stay alive until the great battle against evil was brought to a satisfactory conclusion. In any case, he shared practically nothing with his vice president, leaving him to sign letters of condolence and carry out other routine, mundane functions of the office of Vice President.

The most glaring example of Franklin Roosevelt's cavalier attitude toward former Senator Truman was the fact that he never even brought Vice President Truman into his confidence on the atomic bomb project going on in New Mexico. President Truman had to be informed of the work being done to develop the device by Secretary of War Henry Stimson after he took office.

The most glaring example of Franklin Roosevelt's cavalier attitude toward former Senator Truman was the fact that he never even brought Vice President Truman into his confidence on the atomic bomb project going on in New Mexico. President Truman had to be informed of the work being done to develop the device by Secretary of War Henry Stimson after he took office.

Thus Harry Truman, the man who would not be king, assumed leadership of the nation and much of the world at one of the most critical junctures in history. How was the world to be shaped now that two great, terrible wars had destroyed so much? While the defeat of Germany was virtually assured—Germany surrendered on May 8, less than a month after FDR’s death—the war in Japan was by no means over. During each wartime conference, however, the focus had shifted further and further toward postwar concerns.

(For a fine study of the final months of World War 2, see J. Robert Moskin, Mr. Truman's War: The Final Victories of World War II and the Birth of the Post war World.)

President Roosevelt’s role among the Big Three Leaders—FDR, Churchill, and Stalin—had often been to act as mediator between Churchill and Stalin, who frequently clashed during meetings as they contemplated the world after the defeat of Germany and Japan. By the time of the Yalta Conference in February, 1945, it was apparent that Stalin had little intention of allowing freedom and democracy to flourish in that portion of the world surrounding the Soviet Union. Roosevelt, who was by then gravely ill and exhausted from the long journey to Russia, found Stalin difficult and determined to have his way.

By the time of the Potsdam Conference, held just outside Berlin, Germany, in July, 1945, tensions between East and West had been ameliorated somewhat by satisfaction at the defeat of Nazi Germany. During that meeting, Stalin and President Truman met for the first time. Stalin reassured the president that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan three months after the defeat of Germany, which gratified Truman. The President also took the occasion to inform the Premier of the successful test of the first atomic bomb in New Mexico, and was struck by the lack of surprise shown by Stalin. (As is now well known, Stalin was being informed of progress on the atomic bomb by spies in Great Britain, Canada, and the United States.) The President also informed Prime Minister Churchill, who was replaced during the conference by newly-elected Prime Minister Clement Atlee, of America’s creation of the bomb and his intention to use it.

The Russians had seen their country invaded twice within a century by Napoleon and Hitler, and on both occasions the Russian people had suffered enormous casualties. Stalin was determined not to let that happen again. Furthermore, Communist doctrine called for a worldwide revolution of all workers toward the eventual overthrow of the capitalist system. Indeed the West had meddled in the Russian Revolution following the Bolshevik takeover in 1917, and anti-communist rhetoric and other activities had been pervasive in the West throughout most of the 20th century. The cooperation between the United States and Great Britain and the Soviet Union during World War II can be attributed to the fact that even conservative leaders such as Churchill saw Hitler as the far greater evil facing humanity.

President Truman’s Containment Policy. President Truman’s Cold War policy became one of “containment” of Communism, which meant not challenging the Communists where they were already established, but doing everything possible to see  to it that their sphere of influence did not enlarge itself at the expense of “free” nations. Truman's policy was first explicitly proclaimed in a 1947 speech. Great Britain had been closely monitoring procommunist developments in Greece and Turkey since the end of World War II and had provided financial and military support to the anticommunist governments. Because of her own financial difficulties, however, Great Britain was obliged to cease aid to those nations. Thus the United States was left the responsibility of providing assistance.

to it that their sphere of influence did not enlarge itself at the expense of “free” nations. Truman's policy was first explicitly proclaimed in a 1947 speech. Great Britain had been closely monitoring procommunist developments in Greece and Turkey since the end of World War II and had provided financial and military support to the anticommunist governments. Because of her own financial difficulties, however, Great Britain was obliged to cease aid to those nations. Thus the United States was left the responsibility of providing assistance.

President Truman went before Congress on March 12, 1947, and requested that Congress provide $400 million in military aid and economic assistance for Greece and Turkey, thus articulating what would become known as the Truman Doctrine. That policy would be generally followed by all successive presidents through Ronald Reagan. Truman stated that, “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” The Republican Congress supported Truman’s request, which bespoke the bi-partisan cast of America’s Cold War policy.

See Harry S. Truman, Truman Doctrine Speech, 1947. See also David McCullough’s Truman and the fine HBO film of the same name with Gary Sinese. Truman wrote his own Memoirs as well.

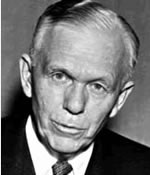

The Marshall Plan. Shortly after President Truman's speech, Secretary of State George C. Marshall gave an address on June 5, 1947, at Harvard University in which he outlined what would become known as the Marshall Plan. Europe was a  long way from recovering from the Second World War, and the harsh winter of 1946-47 had exacerbated the suffering of many Europeans. He stated, “It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos.”

long way from recovering from the Second World War, and the harsh winter of 1946-47 had exacerbated the suffering of many Europeans. He stated, “It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos.”

Secretary Marshall’s plan for massive economic relief, known as the European Recovery Program, provided funds totaling $20 billion to sixteen countries, including Germany. It was justified on humanitarian grounds, but was also clearly designed to help stave off the possible expansion of communism into Western Europe. Marshall offered to include the Soviet Union in his program, but Premier Stalin turned down Marshall’s offer, claiming it was a propaganda tool. The Marshall plan succeeded in both its purposes; it helped restore the European economy (which indirectly aided the American economy as well), and it helped reduce the danger of the growth of communism. Winston Churchill called the Marshal Plan “the most unselfish act by any great power in history.” (See Marshall speech)

Berlin. Following World War II Germany had been divided into four occupation zones allotted to France, Great Britain, United States, and the Soviet Union. The former German capital of Berlin fell within the Soviet sector, and that city was also divided into four zones. Access to the city was by air, and by a strip of land on which a highway and a railroad offered  ground access into West Berlin. Trying to strengthen their hold on the eastern sector, and perhaps irritated by the Marshall plan and anti-Communist rhetoric, the Soviets cut off ground access to Berlin in June, 1948. President Truman's response was the ordering of what became known as the Berlin Airlift. All available transport aircraft were pressed into service and began operating around the clock to provide Berlin with everything its population needed to survive, from food to fuel to clothing and other necessities of life. The Berlin Airlift was carried on into 1949 when the Soviets eventually backed down and reopened the ground access to Berlin. In all, some 2,200,000 tons of supplies were airlifted into Berlin in 267,000 flights. The airlift, which was opposed by some of the President Truman's advisers, was a diplomatic triumph for the president. (Left: Berlin children wave to American pilots.)

ground access into West Berlin. Trying to strengthen their hold on the eastern sector, and perhaps irritated by the Marshall plan and anti-Communist rhetoric, the Soviets cut off ground access to Berlin in June, 1948. President Truman's response was the ordering of what became known as the Berlin Airlift. All available transport aircraft were pressed into service and began operating around the clock to provide Berlin with everything its population needed to survive, from food to fuel to clothing and other necessities of life. The Berlin Airlift was carried on into 1949 when the Soviets eventually backed down and reopened the ground access to Berlin. In all, some 2,200,000 tons of supplies were airlifted into Berlin in 267,000 flights. The airlift, which was opposed by some of the President Truman's advisers, was a diplomatic triumph for the president. (Left: Berlin children wave to American pilots.)

Tensions heightened dramatically in 1949 when the Soviet Union exploded its first nuclear bomb. Until that time the United States had been the sole possessor of those powerful weapons, but now the arms race swung into full gear. The bombs produced in the 1950s eventually grew to dwarf the Hiroshima bomb in explosive power, exceeding its capacity by a factor of 10,000.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization. The continuing tension between the Eastern and Western powers led several European countries to begin considering a mutual defense pact in 1948. The United States and Canada eventually entered into the discussions, as it was apparent that the defense interests of the nations on the western side of the Atlantic coincided with those of Europe. Negotiations continued until a treaty was signed in Washington in April 1949 which created the 12-nation pact of the United States, Canada, and 10 Western European nations. The treaty obligated each member nation to share the responsibility for collective security of the North Atlantic region. For the first time in its history, the United States had seen fit to discard the policy first established by presidents Washington and Jefferson of steering clear of permanent, entangling alliances. NATO was expanded in the 1950s and now includes several nations in Eastern Europe.

Now that the Cold War is over, it is relatively easy to view it objectively. We can ask whether the United States played its cards correctly, and question whether we might have been able to lower tensions sooner and more sharply. Since the U.S. and its allies “won” the Cold War (and one can properly ask whether it is really over), it is easy to say, “Well, of course we played it right—after all, we did win, didn’t we?”

A more critical view might suggest that while Americans have indeed seen the fall of the Soviet Union and much of the apparatus of Communism, during those tension-filled years the U.S. might have pushed its luck so far that the only reason we did not get into a nuclear war was plain good fortune.

In the aftermath of attacks on New York City and Washington on September 11, 2001, Americans certainly understand the fear that comes from threats of violence. Yet during the height of the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s, the fear of nuclear war went beyond the fear of attacks on isolated cities or installations. For a time, the possibility of total nuclear war could not be ruled out. Questions were raised not only about the level of destruction that might result from a nuclear exchange, but also about what life might be like after a nuclear war. In fact, movies like On the Beach, based on the novel by Nevil Shute, raised the possibility of the extinction of all human life on Earth, and few saw that scenario as a far-fetched fantasy

The Cold War Turns Hot: Korea, The Forgotten War

General Douglas MacArthur is one of America's most colorful historic characters. Son of a career army officer, he served over 50 years in the Army and fought in three wars. In 1935 he retired as Chief of Staff of the Army and went to the Philippines, where he took over command of all American and Philippine military forces during the years leading up to World War II. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor they invaded the Philippines. MacArthur was forced to abandon the islands; he retreated to Australia and assumed command of all forces in the Southern Pacific area. From there MacArthur led U.S. forces back through Indonesia and retook the Philippines late in the war. Following the reduction of Okinawa, he and the Navy and Marine forces under Admiral Nimitz began planning the invasion of Japan. Before that could occur, the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought about the Japanese surrender.

As the senior representative of the Allied Powers, MacArthur made a memorable speech about the horrors of war as he accepted the formal Japanese capitulation aboard the U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay in September, 1945. He stayed on as the senior allied occupation officer, and became virtually the acting emperor of Japan. He was a strong force in converting Japan into a modern, democratic state, and was even involved with writing the pacifistic Japanese Constitution. Most Japanese admired MacArthur and were gratified by his moderate, even-handed treatment of the Japanese people during the postwar years. He was truly a benevolent dictator.

(When this author asked a student who was raised in Japan what her countrymen and women thought of MacArthur, she answered, “They thought he was a god.”)

The Korean Peninsula had been a colony of Japan until World War II. In 1945 it was divided at the 38th parallel into two nations. At that time the United States and the Soviet Union jointly administered Korea in a manner similar to the disposition of occupied Germany at the time. Both nations had occupying forces in Korea, the Soviets in the North, Americans in the South. The North Korean government was Communist, the South Korean government non-communist and quasi-democratic, and both claimed sovereignty over the entire peninsula. The situation also resembled what would ensue in Vietnam after the French were defeated in 1954.

In 1949, after American educated strongman Syngman Rhee was elected President of the Republic of Korea (South Korea), the United States withdrew its occupying forces, except for a small advisory command. Soviet forces had withdrawn from the North in 1948. In 1950 North Korean Communist leader Kim Il-sung met with Soviet and Chinese Communist leaders and proposed to take over all of Korea by force. He met no objections from either nation and was offered their support. China repatriated 50,000 Korean soldiers who had fought for the Communists in China’s Civil War, and they became an important element of the North Korean People’s Army. Thus the struggle for control of Korea broke out when the North Koreans crossed the 38th parallel in force in 1950.

War Breaks Out. In June, 1950, North Korean troops surged across the border into South Korea, triggering the first major confrontation between the forces of the communist and non-communist worlds. The United States, which had occupied South Korea as part of the post-war administration of former Japanese colonies, became immediately involved in the war. Critics of American foreign policy claimed that when the Truman administration adopted its containment policy, the theoretical line drawn around areas that would be protected against communist aggression failed to include Korea. In addition, because the U.S. was preoccupied with affairs in Europe as well as rebuilding Japan on a democratic footing, North Korea’s Kim Il-sung and his Chinese and Soviet counterparts felt that the United States would not defend Korea. President Truman, however, contradictory to what others might have believed, decided immediately that, in keeping with his containment policy, the United States would come to the aid of South Korea. He appealed immediately to the United Nations for support, and was rewarded with a unanimous vote in the UN Security Council calling for a military defense of the Republic of Korea. For the first time, an international body voted to oppose aggression by force.

War Breaks Out. In June, 1950, North Korean troops surged across the border into South Korea, triggering the first major confrontation between the forces of the communist and non-communist worlds. The United States, which had occupied South Korea as part of the post-war administration of former Japanese colonies, became immediately involved in the war. Critics of American foreign policy claimed that when the Truman administration adopted its containment policy, the theoretical line drawn around areas that would be protected against communist aggression failed to include Korea. In addition, because the U.S. was preoccupied with affairs in Europe as well as rebuilding Japan on a democratic footing, North Korea’s Kim Il-sung and his Chinese and Soviet counterparts felt that the United States would not defend Korea. President Truman, however, contradictory to what others might have believed, decided immediately that, in keeping with his containment policy, the United States would come to the aid of South Korea. He appealed immediately to the United Nations for support, and was rewarded with a unanimous vote in the UN Security Council calling for a military defense of the Republic of Korea. For the first time, an international body voted to oppose aggression by force.

President Truman then ordered American naval and air forces to begin supporting the South Korean army. When it became apparent that the North Korean army could not be stopped by naval and air support alone, the President made the decision to commit ground forces to Korea. As the Security Council resolution had called for all nations with adequate military forces to contribute to South Korea’s defense, other nations such as Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia prepared to send military units to Korea. The United States, however assumed the major share of the burden of fighting the Korean War. President Truman named General Douglas MacArthur, America’s supreme commander in the Far East, commander of all forces to be engaged in Korea.

As Commander of all United Nations forces, General MacArthur immediately dispatched available ground units to Korea. Having been involved only in occupation duty since 1945, however, the American troops were ill prepared and ill equipped for combat against a well-trained army. Sent to Korea piecemeal, they, along with the South Koreans, were soon driven into a defensive perimeter around the South Korean port of Pusan, and for a while it looked as though North Korea would gain firm control of the entire nation. MacArthur visited the American troops in the Pusan perimeter and told their commanding general that his men would have to hold on while MacArthur prepared a countermove. If they were driven off or captured, retaking the peninsula would be an extremely difficult task.

Back in Japan General McArthur and his staff examined their options and came up with a bold proposal, which he submitted to the Joint Chiefs of Staff for approval. MacArthur’s plan called for an amphibious invasion of South Korea at the port of Inchon, not far below the 38th parallel. It was a daring move, as the attack would fall well behind North Korean lines. A variety of factors helped make MacArthur’s surprise move an unqualified success.

First, Inchon was an unlikely site for an invasion because of its high tidal swings, meaning that the enemy would not expect a landing there. Second, the geography of South Korea meant that the North Korean supply lines could be severed  with a quick strike inland from Inchon. In addition, Inchon was near the capital of Seoul and Kimpo airfield, the capture of which would be valuable. The First Marine Division under the command of Major General Oliver P. Smith and the 7th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General David G. Barr, conducted the landing, successfully capturing Seoul and Kimpo airfield in the process. The North Korean army, its supply lines severed, fell back in disarray across the 38th parallel. The breakout of American and Korean forces from Pusan soon followed.

with a quick strike inland from Inchon. In addition, Inchon was near the capital of Seoul and Kimpo airfield, the capture of which would be valuable. The First Marine Division under the command of Major General Oliver P. Smith and the 7th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General David G. Barr, conducted the landing, successfully capturing Seoul and Kimpo airfield in the process. The North Korean army, its supply lines severed, fell back in disarray across the 38th parallel. The breakout of American and Korean forces from Pusan soon followed.

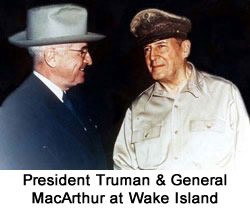

As American naval air and ground units entered the fray, and as the South Korean Army pulled itself together, the UN forces pursued the North Korean Army across the border. South Korea was once again secure. It does not go too far to claim that at that juncture, the Korean War had been won—the invasion had been repelled. General MacArthur chose to push the North Korean army back toward the Chinese border, however, feeling that China would not dare to intervene in the conflict. In a meeting with President Truman at Wake Island, he assured his commander-in-chief that Chinese intervention was unlikely. President Truman was aware that China had threatened to intervene in Korea, communicating their intent via neutral embassies. Truman felt the Chinese were bluffing. Both he and General MacArthur were wrong.

In November 1950 on Thanksgiving Day, a huge Chinese army swept across the border and soon drove the Americans back in the direction from which they had come. Part of that painful withdrawal included the movement of the First Marine  Division and the Seventh Army Division from the Chosin Reservoir area, a fighting withdrawal that took place in bitter cold weather. “Frozen Chosin” became an epithet for the painful process of extricating American troops from what had seemed a virtual death trap. The gains that had been made at great sacrifice were mostly lost, as the North Korean army once again crossed into South Korea and recaptured the capital of Seoul.

Division and the Seventh Army Division from the Chosin Reservoir area, a fighting withdrawal that took place in bitter cold weather. “Frozen Chosin” became an epithet for the painful process of extricating American troops from what had seemed a virtual death trap. The gains that had been made at great sacrifice were mostly lost, as the North Korean army once again crossed into South Korea and recaptured the capital of Seoul.

To bolster his defenses General MacArthur sought permission to attack Chinese forces across the Yalu River in Chinese territory. He wanted hit the Chinese army in their sanctuary. He believed that attacking bases from which the Chinese army was being supplied was a key to defeating them in South Korea. The Truman administration, not wishing to escalate the crisis nor provoke a full, all-out war between United States and Communist China, restricted MacArthur's movements to the territory of North Korea. When informed that he might bomb the southern half of bridges over the Yalu River, MacArthur fumed, “In all my years of military service I have never learned how to bomb half a bridge!”

Uncomfortable with the Truman administration's policies, General MacArthur openly criticized his commander-in-chief and sent a letter to a Republican congressman which was released to the public. After consultation with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, President Truman relieved the five-star general of his command for insubordination.

President Truman’s firing of General MacArthur, one of the great heroes of the Second World War, the man who accepted the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay on behalf of all Allied forces, caused a firestorm of criticism. When the general returned to the United States, he was fêted in New York with the largest ticker tape parade ever conducted in that city. He was greeted by enthusiastic admirers as he toured the country, accepting salutes and parades in his honor in a number of cities. In his farewell address to a joint session of the United States Congress, he gave a moving speech in which he claimed that, “In war there can be no substitute for victory.”

See MacArthur’s Farewell Address to Congress. See also William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880 - 1964 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1978), one of several biographies. MacArthur also wrote his own memoir, Reminiscences. An excellent 1977 film, MacArthur, starring Gregory Peck, was directed by Joseph Sargent.

President Truman replaced General MacArthur with General Matthew Ridgway, another World War II veteran, and General Ridgway soon began reclaiming some of the ground that had been lost following the Chinese invasion. But further attempts to push the war back to the Chinese border were not feasible, and the fighting degenerated into a stalemate around the 38th parallel. In the presidential election campaign of 1952, General Eisenhower, the Republican candidate, promised that if elected he would go to Korea and seek a solution to the conflict, a promise he fulfilled. Eventually a cease-fire was agreed upon and the fighting came to a desultory conclusion. That cease-fire, however, was not quite the same thing as peace, and tensions along the border between North and South Korea continued for many years. At the current time, American troops are still stationed in South Korea.

The Aftermath of Korea. During the years since the fighting ended, response to the Korean War has been mixed. At the time, returning veterans of Korea discovered that their fellow Americans seemed almost totally ignorant of the war they had just fought. The conclusion of the war—a negotiated truce rather than a victory—left a sour taste with many Americans, for whom memories of the overwhelming victories of the Allies over Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were still relatively fresh. Some immediate good came from the war, however; the United States Army that started fighting in Korea in 1950 was undertrained, under-disciplined, and under supplied. After several years of combat in Korea, the United States Army had been restored to good fighting condition. For all its frustrations, the war had what was ultimately a successful outcome: South Korea retained its freedom and became a prosperous, democratic and economically viable nation.

The Aftermath of Korea. During the years since the fighting ended, response to the Korean War has been mixed. At the time, returning veterans of Korea discovered that their fellow Americans seemed almost totally ignorant of the war they had just fought. The conclusion of the war—a negotiated truce rather than a victory—left a sour taste with many Americans, for whom memories of the overwhelming victories of the Allies over Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were still relatively fresh. Some immediate good came from the war, however; the United States Army that started fighting in Korea in 1950 was undertrained, under-disciplined, and under supplied. After several years of combat in Korea, the United States Army had been restored to good fighting condition. For all its frustrations, the war had what was ultimately a successful outcome: South Korea retained its freedom and became a prosperous, democratic and economically viable nation.

The Korean War provided lessons that might have been well applied to Vietnam. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, the Korean War did not substantially prepare the United States for its next involvement on the Asian mainland. The enemy faced in Korea was not the same as the enemy faced in Vietnam. One lesson that the West failed to learn from both the Korean and Vietnamese experiences, however, is that many of the communist leaders both in Korea and in Vietnam were far more nationalistic than communist. What they sought for their nations rose above mere ideology. One positive result of both wars, however, was that the United States chose not to use tactical nuclear weapons in Korea, for which the world may be properly grateful. Had that door been opened, there is no telling what the outcome might have been.

Although no final judgment can be offered even half a century after the end of the Korean fighting, the opinion of historian Max Hastings has some merit:

If the Korean War was a frustrating, profoundly unsatisfactory experience, more than 35 years later it still seems a struggle that the West was utterly right to fight. (Max Hastings, The Korean War, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987, p. 344.)

As many Americans stationed in Korea have said, the Korean people to this day are grateful to the Americans who gave their lives in defense of that nation.

McCarthyism: The Cold War at Home. As the Cold War progressed, and as the presence of Soviet spies operating in the West, including in the United States, became known, many Americans began to see Communism is an immediate threat to their way of life. With revelations of the spying of Klaus Fuchs, who had smuggled atomic bomb secrets out of New Mexico, and as Alger Hiss and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were revealed to be spies, a fear gripped much of America. Thus by 1950 the time was ripe for a demagogue to seize the issue of anti-Communism and turn it to his own ends. What resulted was one of the most disgraceful episodes in American politics. That trend had already begun with the blacklisting of anyone in Hollywood or other areas of the country about whom it could be claimed that they had the slightest degree of sympathy for the Communist movement. Hundreds of lives were disrupted. (See Guilty by Suspicion starring Robert De Niro, 1991.)

Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, who had served with the Marines in World War II, though he had seen no combat, was elected to the Senate in 1946. (He later lied about his military record, claiming to have seen action.) Looking for an issue on which to run for reelection in 1952, McCarthy hit on the idea of anti-Communism, which he certainly did not have to invent. He launched his “project” with a speech in February, 1950. The press zeroed in on McCarthy's charges, which sounded serious (though they were in fact fabricated), and McCarthyism was born.

Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, who had served with the Marines in World War II, though he had seen no combat, was elected to the Senate in 1946. (He later lied about his military record, claiming to have seen action.) Looking for an issue on which to run for reelection in 1952, McCarthy hit on the idea of anti-Communism, which he certainly did not have to invent. He launched his “project” with a speech in February, 1950. The press zeroed in on McCarthy's charges, which sounded serious (though they were in fact fabricated), and McCarthyism was born.

Taking the already present suspicion and fear of the Soviets to new levels, McCarthy went on a frantic chase after Communist conspirators, who he claimed existed in virtually every corner of American life. With little or no evidence, he carried out what can only be called a witch hunt, ruining lives and reputations in the process and eventually bringing himself into disgrace.

McCarthy attacked all branches of government, including the State Department and the U.S. Army, the latter of which proved more than a match for McCarthy’s recklessness. In a series of televised hearings, McCarthy and aide Roy Cohn (many called him McCarthy’s hatchet-man) tangled with a tough Army lawyer named Joseph Welch. Welch put Cohn on the spot over some doctored photographs. When McCarthy tried to protect his protégé by slandering a lawyer in Welch’s law firm, Welch turned on McCarthy with a withering indictment. He accused the Senator in front of television cameras of being shameless and dishonorable, as spectators applauded.

The first Senator to attack McCarthyism on the floor of the Senate was Republican Margaret Chase Smith of Maine. She called for an end a smear tactics in her “Declaration of Conscience” speech, although she did not mention McCarthy by name. McCarthy was eventually censured by the Senate. An alcoholic, McCarthy died in 1957, but much of the damage done by the Senator and his aides such as Roy Cohn could not be repaired. One such casualty was J. Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, whose top-secret security clearance was suspended in 1953 because of his alleged leftist sympathies during the 1930s.

Dwight D. Eisenhower: The General as President

Dwight David Eisenhower was born in Texas in 1890, one of six brothers who grew up in Abilene, Kansas. He entered West Point in 1911 and served in the Army during the 1920s and 30s under such illustrious officers as George Patton and Douglas MacArthur. Recognized early for his powerful intelligence and devotion to duty, he held important positions in the years preceding World War II and helped develop doctrine for armored warfare. When World War II broke out, he was brought to Washington to work for General George C. Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff, serving as Chief of the War Plans Division.

In 1942 General Eisenhower went to Europe to take command of American forces for the invasion of North Africa, Operation Torch, in 1942. He was subsequently named Supreme Commander Allied Forces Europe and planned and oversaw Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944. As Supreme Commander, he dealt with many challenging personalities, including Winston Churchill, French General Charles de Gaulle, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, senior Soviet Russian officials and his military and civilian superiors in Washington.

A measure of Eisenhower’s character is revealed in a message he prepared in advance of the landings in Normandy on D-Day:

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.

Fortunately, the general never had to release that message.

When World War II ended in Europe, General Eisenhower accepted the surrender of German leaders and took steps to reveal the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps. (He accurately predicted that at some future time people would deny that the events called the Holocaust ever occurred. His quotation about that prediction is inscribed on the rear wall of the Holocaust Memorial in Washington, DC.)

Following the war, General Eisenhower replaced George C. Marshall as Chief of Staff of the Army. Partly as a reward for his service, and mostly because of his demonstrated leadership skills, Eisenhower held several important positions following his retirement from active duty. In 1948 he became president of New York’s Columbia University, a position which allowed him to be involved in high-level discussions of American foreign policy. In the process, he made many useful contacts and learned more about the workings of the American political system. (He once claimed to have been so little involved in politics that he had never even voted.) Until President Harry Truman decided to run for reelection in 1948, the Democrats had been considering Eisenhower for their candidate. In 1952 a movement began among senior Republicans to nominate General Eisenhower as their candidate for president.

Eisenhower faced a strong challenge from conservative Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, the front runner for the nomination, who was known as “Mr. Republican.” Following a tough battle at the Republican Convention, Eisenhower won the nomination on the first ballot. He selected California Senator Richard Nixon for vice president. With his grandfatherly image and the slogan “I like Ike,” he comfortably defeated Democratic candidate Democratic Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois with almost 58% of the popular vote. Eisenhower thus became the first former general to enter the White House since Ulysses S. Grant.

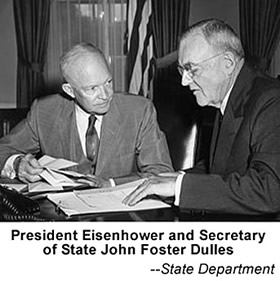

President Eisenhower is Sworn in as outgoing President Truman Looks On

When Dwight D Eisenhower assumed the presidency on January 20, 1953, twenty years of Democratic Party occupancy of the White House ended. President Eisenhower was the only former general to occupy that office in the 20th century, and he was extremely well prepared for the position. What served the former soldier well as he entered office when Cold War tensions threatened was his experience in dealing with other world leaders during the Second World War. He dealt with future adversaries such as top generals of the Russian Army, prickly allies like France's Charles de Gaulle, and powerful Allied leaders like Winston Churchill. As leader of the largest and most complex military operation ever undertaken by Americans—the invasion of Europe and conquest of Nazi Germany—he had management experience of the highest order.

President Eisenhower and the Cold War. President Eisenhower's most significant challenges came in the area of foreign-policy. Tensions had begun to arise between the Soviet Union and the West even before World War II was over. The Soviets had recently developed a powerful nuclear arsenal, and the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 heightened the uncertainty of relations with the communist world. Thus, by the time Eisenhower took office in January 1953, the Cold War, which had been underway for practically a decade, had reached a dangerous level. Anti-Soviet feelings ran deep; the McCarthy era was in full swing. Americans, enjoying products that had sprung from the technologies and events during World War II and dealing with civil rights issues, were not completely focused on foreign affairs.

Those who have examined the political career of General Eisenhower (as he preferred to be called even after becoming president) have generally agreed that he was a shrewd observer of the world scene. Yet he was sometimes naïve in his understanding of American political practice. He seemed to some to be working too hard to appease his political opponents, lacking the experience of having dealt with a “loyal opposition.” At the same time, he guided American foreign affairs in a cautious, measured fashion.

No American politician could ignore the threat posed by the Soviet Union, especially as the nuclear arms race had begun to produce weapons of stupefying power, thousands of times more powerful than the bombs which had destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Assisting in the formulation of Eisenhower's foreign policy was Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who took a stern view of the Soviets. Dulles’s brother, Allen Dulles, was Director of Central Intelligence (CIA) and contributed to the administration's harsh view of the Soviets.

| The first nuclear bomb, a hydrogen bomb, is exploded in a test on a Pacific Ocean atoll on November 1, 1952. Three days later, General Dwight Eisenhower was elected President of the United States over Governor Adlai Stevenson. |

Like all postwar presidents, including his predecessor, Harry Truman, President Eisenhower felt that the greatest threat to America came from an expansive, monolithic communism centered in the Soviet Union. He stated in his first inaugural address that, “Forces of good and evil are massed and armed and opposed as rarely before in history. Freedom is pitted against slavery, lightness against dark,” those being reasons why he named John Foster Dulles as Secretary of State. The Eisenhower-Dulles foreign policy was, at least in its rhetoric, harsher than that of President Truman; Dulles coined the phrase “massive retaliation,” which was to be used if the Soviets became aggressors.

Eisenhower was comfortable allowing Secretary Dulles to heat up the rhetoric of the Cold War while he himself worked more quietly behind the scenes to reduce international tension. The new president was far more clever than his critics at the time realized. An avid golfer, Eisenhower had a putting green installed on the south lawn of the White House, and a popular ditty had the president “putting along” as the world around him seethed. In fact, the president was deeply engaged in monitoring foreign affairs and was well aware of how dangerous the world had become.

Eisenhower was comfortable allowing Secretary Dulles to heat up the rhetoric of the Cold War while he himself worked more quietly behind the scenes to reduce international tension. The new president was far more clever than his critics at the time realized. An avid golfer, Eisenhower had a putting green installed on the south lawn of the White House, and a popular ditty had the president “putting along” as the world around him seethed. In fact, the president was deeply engaged in monitoring foreign affairs and was well aware of how dangerous the world had become.

When the Hungarians revolted against their Soviet oppressors in 1956, there were calls for the United States to intervene to help the freedom fighters. Even if Eisenhower had been tempted to act, however, getting aid to landlocked Hungary would have been a monumental undertaking. The Soviets quickly repressed the revolt in any case. Yet the episode led some to believe that the United States under President Eisenhower was slow to respond to calls from assistance by those beleaguered by international communism.

In 1954 when the French Army found itself in a critical situation in Indochina, President Eisenhower declined to support the French at Dien Bien Phu with military assistance. He did, however, offer military and economic aid to South Vietnam. He defended his action by describing what became known as the Domino theory—that if one nation fell to communism, other nations would certainly follow.

An additional crisis erupted in the Middle East in 1956. In 1955 the Soviet Union had begun arms shipments to Egypt. In response, Israel strengthened its defenses and requested arms from the United States, a request that president Eisenhower rejected, fearing a Middle East arms race. When United States canceled a loan offer of $56 million to Egypt for construction of the Aswan Dam, Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had grown closer to the Soviet Union, took action to nationalize the Suez canal and extract tolls from users. Israel responded by advancing troops toward the Suez Canal, and Britain and France began airstrikes against Egypt. British and French leaders called for assistance from the United States, but president Eisenhower refused on the grounds that he did not support the use of force in the settlement of international conflicts.

Fearing that the Soviets would come to dominate the Middle East, Eisenhower and his Secretary of State Dulles requested a resolution from Congress authorizing the president to extend economic and military aid to Middle Eastern nations. He based his request on the following principle:

We have shown, so that none can doubt, our dedication to the principle that force shall not be used internationally for any aggressive purpose and that the integrity and independence of the nations of the Middle East should be inviolate. Seldom in history has a nation's dedication to principle been tested as severely as ours during recent weeks. …

Let me refer again to the requested authority to employ the armed forces of the United States to assist to defend the territorial integrity and the political independence of any nation in the area against Communist armed aggression. Such authority would not be exercised except at the desire of the nation attacked. Beyond this it is my profound hope that this authority would never have to be exercised at all. (Dwight D. Eisenhower, Message to Congress, January 5, 1957.)

Congress responded by granting the president the authority to use force to protect nations threatened by communism. This policy became known as the “Eisenhower Doctrine.” While deploring the use of force, Eisenhower recognized that the threat of force could be a deterrent to its use. In response to a request from the President of Lebanon, President Eisenhower sent 5,000 Marines into that country to protect Lebanon’s territorial integrity. They remained there for three months.

Although criticized in some quarters for his inaction in the Suez Crisis, Eisenhower was as aware as anyone on the planet of the horrors that could be unleashed by another widespread war, now made an even more terrifying prospect because of the spread of nuclear weapons. With new and more powerful hydrogen bombs being built, the Eisenhower administration followed a policy designed to use the threat of nuclear war only as a deterrent to the Soviet Union in case vital United States interests should be threatened. Eisenhower also rejected any possible use of atomic or nuclear weapons in defense of French Indochina or Taiwan. In retrospect, Eisenhower's cautious policy has been deemed wise and prudent, given the volatility of international relations in the 1950s. The rhetoric of “massive retaliation” was strong, but a first use of nuclear weapons probably never entered President Eisenhower’s consciousness; like General MacArthur, he abhorred the use of atomic or nuclear weapons. His recent biographer, Jim Newton describes Eisenhower in these words:

Shrewd and patient, moderate and confident, Ike guided America through some of the most treacherous moments of the Cold War. He was urged to take advantage of America’s military advantage in those early years—to finish the Korean War with nuclear weapons, to repel Chinese aggression against Taiwan, to repulse the Soviets in Berlin, to rescue the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu. … Eisenhower was not complacent, nor was he reckless or unhinged. (See Jim Newton, Eisenhower: The White House Years (New York: Doubleday, 2011.)

Dwight Eisenhower might be considered a great American for things he did not do as well as for those he did. Later in his life he reflected: “The United States never lost a soldier or a foot of ground in my administration. We kept the peace. People ask how it happened—by God, it didn't just happen, I'll tell you that.”

|

Left. General Eisenhower was in Europe when he heard that President Truman had fired General MacArthur from command in Korea and replaced him with General Matthew Ridgway. Ike responded, “I'll be darned.” Eisenhower had worked under MacArthur in the Philippines and in Washington for much of the 1930s. The two men did not get along, and Eisenhower resented MacArthur's repeated attempts to divert military supplies from Europe to the Pacific during World War 2. MacArthur was determined to get back to the Philippines as early as possible nad pestered Washington for more assistance. Hearing of Eisenhower's election to the White House in 1952, MacArthur expressed his opinion that Eisenhower would surely be an excellent president. He said, "Ike was the best clerk I ever had." |

In 1952, in keeping with a campaign promise, President-elect Eisenhower visited Korea in hopes of achieveing a settlement. A cease-fire agreement was arranged in 1953, and the fighting ended. Skirmishes and minor actions occurred along the 38th parallel for years, however. |

Sputnik: The Space Race Begins. In the years following World War II blustering Soviet propaganda had provided ammunition for comedians who suggested that the Russians were all talk and no action. When they exploded their first nuclear device in 1949, however, the jokes quickly fell flat. When the Soviet Union launched the first Earth satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, the reaction among many Americans was close to panic. Fears of the military use of space ran rampant, and the United States was placed on a crash course to match the Soviet achievement. The American educational system came under severe criticism suggesting that “Ivan” was far better educated than “Johnny,” especially in math, science and engineering.

With the knowledge that the missiles used by the Soviets to launch satellites into space could also be used to rain warheads on the United States, Eisenhower authorized surveillance flights by U-2 aircraft over the Soviet Union. The high flying spy planes were thought to be invulnerable to anti-air missiles, but in 1959 a U-2 aircraft (left) piloted by Major Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union. The administration initially issued denials, but when pictures of the U.S. airman and the downed aircraft were shown on Soviet television, it was clear that the story was real. When President Eisenhower refused to issue an apology, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev canceled a scheduled summit meeting with the president, which further heightened tensions. Despite President Eisenhower’s caution, the world was still a dangerous place.

Shortly before his departure from the White House, President Eisenhower, following the example first set by George Washington, delivered a farewell address to the nation on radio and television, in which he cautioned the American people of the forces that threatened to take over the direction of American foreign policy. The speech has become known as his “Military-Industrial Complex Speech.” In the course of his remarks he said:

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. … We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. …

Today … the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. … The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present -- and is gravely to be regarded.

Another factor in maintaining balance involves the element of time. As we peer into society’s future, we—you and I, and our government—must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering for our own ease and convenience the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.…

Disarmament, with mutual honor and confidence, is a continuing imperative. Together we must learn how to compose differences, not with arms, but with intellect and decent purpose. Because this need is so sharp and apparent, I confess that I lay down my official responsibilities in this field with a definite sense of disappointment. As one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war, as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization which has been so slowly and painfully built over thousands of years, I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.…

(Full text of President Eisenhower’s Farewell Address.)

An observer of the administration of John F. Kennedy once noted, “You are the staff officers of World War II, come of age.” The observer went on to comment that the Kennedy staffers had seen many things handled poorly during that earlier conflict, and they were determined to do things right. History has yet to conclude decisively whether or not that noble ideal was reached.

An observer of the administration of John F. Kennedy once noted, “You are the staff officers of World War II, come of age.” The observer went on to comment that the Kennedy staffers had seen many things handled poorly during that earlier conflict, and they were determined to do things right. History has yet to conclude decisively whether or not that noble ideal was reached.

Joseph P. Kennedy, a wealthy businessman and movie tycoon, was determined that one of his sons would become the first Irish-Catholic president of the United States. When his son, Joseph P. Kennedy Jr., was killed in a bombing mission during World War II, the mantle passed to his next oldest son, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Young Jack Kennedy, who had commanded a PT boat during the war, ran successfully for Congress in 1946 and was elected to the Senate in 1952. He married Jacqueline Bouvier in 1953 and was runner-up for the vice presidential nomination in 1956. The publicity gained from that experience enabled him to gain the Democratic nomination in 1960. He defeated Vice President Richard Nixon in a very close election.

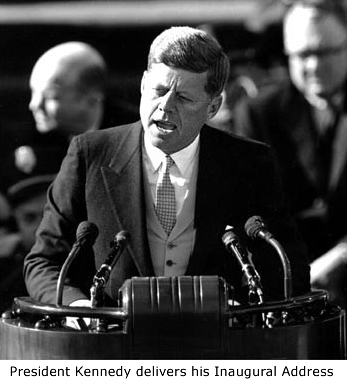

President Kennedy’s inaugural address set the tone for his foreign policy; people looking back on it have often noted how much it seemed to foretell coming events, especially in its military imagery. Consider his words:

Let the word go forth … that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a cold and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage—and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed …

Let every nation know, whether it wish us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend or oppose any foe in order to assure the survival and success of liberty.

To those peoples in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required—not because the Communists are doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If the free society cannot help the many who are poor, it can never save the few who are rich.

Let all our neighbors know that we shall join with them to oppose aggression or subversion anywhere in the Americas. And let every other power know that this Hemisphere intends to remain the master of its own house.

As a combat veteran of World War II, Kennedy viewed himself and his administration as Cold Warriors. His father had been ambassador to Great Britain during the years leading up to World War II, and Kennedy's oldest brother, Joe, was killed in that conflict. The rhetoric of JFK’s inaugural address was filled with military imagery. He saw himself as a fighter, and many Americans were prepared to follow his lead.

Once Kennedy was in office, however, it soon became apparent that his counterpart in the Soviet Union, Premier Nikita Khrushchev, saw him as young, inexperienced and perhaps naïve. Kennedy set out to prove him wrong. It is believed that his first face-to-face confrontation with Khrushchev in Vienna is what led him to increase American support for the anti-communist Diem government in Vietnam. No doubt it also led him to play hardball with the Russians during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. He reorganized the Joint Chiefs of Staff to find generals who would share his view of the world; indeed, a number of them were far more hard-line than the president.

The Bay of Pigs. As the McKinley administration was preparing to go to war with Spain in 1898, the anti-imperialist movement in the United States was growing in influence. One result was the Teller Amendment, attached to a key piece of war legislation, which stated that the United States was not going to war for the purpose of annexing Cuba. Although the U.S. did intervene very heavily in that nation following its independence from Spain, America stuck by its pledge and Cuba remained independent.

During the 1950s Cuba was ruled by the dictator Fulgencio Batista. One wry observer noted that “Batista may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.” The comment meant that whatever his flaws, Batista was staunchly anti-Communist. The revolution led by Fidel Castro began in 1953 and ended by driving out the Batista regime in 1959. Shortly after Castro took power, it became apparent that his sympathies lay with Communism and that he intended to rule Cuba with an iron hand. Many of Batista's government officials and soldiers were executed, and religious and other civil institutions were clamped down severely.

The idea of a communist nation 90 miles off the coast of Florida did not sit well with most Americans. During the early years of the Castro regime the Eisenhower administration and the CIA began catering to a group of so-called Cuban patriots, “freedom fighters,” who were determined to invade Cuba. Their goal was to reverse the Castro revolution and end his control of the country. A small army of freedom fighters was trained in Guatemala with American support. The rebels came to believe that they could depend on full American assistance and cooperation, if not an outright declaration of war on the Castro government, once the operation began.

Before that plan was executed President Eisenhower left office and was replaced by the young John F. Kennedy. Kennedy assumed office in January, 1961, and by April of that year the invasion plan was ready to be put into action. Those who have since examined the plan and the resources provided quickly saw that it was bound for disaster and never had any real chance of success. Nevertheless, President Kennedy, as the youngest man ever elected president, did not want to appear weak in the conduct of foreign policy, and he let the plan proceed.

]The idea was to land a small force at the Bay of Pigs in southern Cuba, with the expectation that patriotic citizens would join the invasion force and eventually overthrow Castro's government. The success of a C.I.A. inspired coup to overthrow a leftist regime in Guatemala in 1954 had led the C.I.A. to believe a similar plan would succeed in Cuba. Although planning for the operation was ill-conceived, it took on a momentum of its own. The C.I.A. foolishly believed that American involvement could be kept secret. The area chosen for the landing was one in which Castro had strong support among the people. The military, feeling it was a C.I.A. operation and thus none of its business, kept its objections to the plan to itself. President Kennedy erroneously believed that since President Eisenhower, a career soldier, approved of the plan, it must be sound, when in fact Eisenhower had been only marginally involved in the planning process.

The invasion was a dismal failure, and within a matter of hours the entire invasion force was either killed or captured. Bitter recriminations followed, as the rebels claimed that America had not provided the promised support. The fact is that the Kennedy administration had no intention of backing an all-out invasion of Cuba. When things turned bad for the invaders, Kennedy cancelled further air support in hopes of concealing American involvement. It was too late for that, however. Far many reasons, the plot was doomed to failure from the beginning.

Because Kennedy had only been in office for a few months when the Bay of Pigs fiasco took place, he was able to publicly accept full responsibility for the operation, understanding full well that any critic must know that it had been in the works for months before Kennedy took office. His personal charisma earned him high marks for candor even as he delivered the bad news. His defenders were able to say that he did not want to reverse a policy begun by General Eisenhower, and thus he allowed the operation, about which he himself was skeptical, to go forward.

The Bay of Pigs had a significant impact on the future of the Kennedy administration foreign policy. Soviet Premier Khrushchev saw it as a sign of Kennedy's inexperience and naivety. Thus when Kennedy and Khrushchev met later in Vienna, Khrushchev was rough with Kennedy and blustered about how the Soviet Union would eventually crush the United States. Kennedy returned from Vienna shaken but determined not to be pushed around by the Soviets. Two months later Khrushchev sealed off the border between East and West Berlin and built a wall to prevent East Germans from escaping into West Berlin. Vice President Johnson was sent to Germany to reassure the German people, but the Cold War had escalated once again.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962

The Kennedy Legacy. The question still discussed about President Kennedy’s foreign policy—one for which there is no satisfactory answer—is: “What would Kennedy have done in Vietnam if he had not been assassinated?” Some believe that he was prepared to end what he saw as a misguided venture; however, advisers close to the Kennedy administration have indicated that if his intent was to begin a full withdrawal from Vietnam, they had seen little evidence that he would carry it further. True, he had drawn down the number of advisers in Vietnam slightly during the last months of his presidency, but some believe that that was just preparation for the election of 1964. We can only speculate about the later course of events if Kennedy had not been shot.

In the end, Kennedy followed the path of Presidents Truman and Eisenhower as a leader determined to prevent the further spread of Communism in the world by all reasonable means. He had campaigned on the issue of a missile gap between United States and the Soviet Union, and even his plan to place a man on the moon in the decade of the 1960s was, to a large extent, aimed at defeating the Russians in space. The military implications were obvious. It was during Kennedy's administration that the most dangerous point in the Cold War was reached: the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962.

| Post World War 2 Home | Post-World War 2 Domestic | Updated February 4, 2018 |