Copyright © Henry J. Sage 2012

Remembering the Depression. Not many people are still alive who remember the Great Depression. Older people probably had parents or grandparents who lived through the Depression, and they may have transmitted their memories of that trying time to their children and grandchildren. For younger Americans, the Great Recession that began in 2007-2008 following the crash of the housing bubble may be a point of reference. In that latter economic crisis, thousands of people lost their homes and unemployment soared. People saw great chunks of their life savings shrink as the stock market plunged. Nevertheless, that experience is in many ways not quite comparable to the Great Depression of the 1930s. What we have instead are documents, books, and films such as "Grapes of Wrath," adapted from the great novel by John Steinbeck. In this section we will attempt to convey what that period was about, both in the economic collapse, and in the attempts to remedy the situation through President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal.

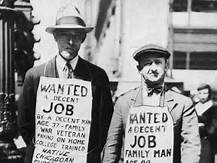

Imagine these scenes:

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Scenes like the ones above, as described in Caroline Bird’s Invisible Scar: The Great Depression, were common during the Great Depression, a time that is difficult for those of us living in the 21st century to imagine existing in America. Suicide became so common that people made bad jokes about it. Thousands of people lived in cardboard shacks, drainpipes, and tent camps on the fringes of America’s most affluent cities. Once prosperous men in three-piece suits stood in line for a piece of bread or a cup of soup. People stopped looking for jobs when it was apparent that there were no jobs to be had. How did it come about? In the 1920s nobody thought an economic disaster of such proportions could ever touch the United States. In the aftermath of the Great War, while Europe was still cleaning up the mess, caring for the wounded, and mourning the dead, Americans felt a sense of disdain for the rest of the world. They saw a European-centered world that could not manage its affairs any better than it had done in the past. America had problems of its own to be sure: racism, religious differences, adjustments to the post-industrial age. But the mood of the 1920s was upbeat and positive, and as President Coolidge said, the business of America was business. Then, on a day known as Black Tuesday, the market crashed, and within months the economic downturn was in full swing. It would be more than a decade later, when the massive government spending associated with World War II restored full economic health to the nation. |

|||

The Depression was caused by many factors, but it was triggered by the stock market crash. The huge increases in production through the application of new methods and technologies during the 1920s had an unintended consequence—excessive supply reduced demand, which in turn meant lower prices for consumer goods. At the same time, an increase in credit buying had caused the demand for consumer goods to rise artificially. As people stopped buying at an inflated rate, however, merchants found they could not sell their products. Orders to factories dried up, and factory workers were laid off. Thus personal incomes continued to fall, and the cycle repeated over and over in a downward spiral. The country produced and sold 8 million cars in 1928 and 2 million in 1932. Unemployment percentages varied from 15 percent to 25 percent, and even higher in some areas. In hard-hit regions such as Appalachia, entire towns seemed to be hopelessly trapped in poverty.

The depth of the Great Depression is difficult for us to fathom in these times of prosperity in the early 21st century. Recent recessions, upheavals in various sectors of the economy, layoffs, home foreclosures, bankruptcies and other casualties, as trying as they may be for those who suffer them, cannot compare  with the massive losses of the 1930s. The loss of human dignity, the hopelessness and despair, the humiliation that many men felt at not being able to provide for their families is almost beyond out comprehension. There was hardly a sense of promise, a feeling that “this too shall pass.” Those feelings did not pass for a long time, and for some there seemed no way out but suicide. So frequent were the suicides that newspapers actually ran cartoons or comments on the phenomenon, perhaps in an attempt to cheer people up. It did not work—the Depression went on, and on, and on. Many Americans never got over the shock.

with the massive losses of the 1930s. The loss of human dignity, the hopelessness and despair, the humiliation that many men felt at not being able to provide for their families is almost beyond out comprehension. There was hardly a sense of promise, a feeling that “this too shall pass.” Those feelings did not pass for a long time, and for some there seemed no way out but suicide. So frequent were the suicides that newspapers actually ran cartoons or comments on the phenomenon, perhaps in an attempt to cheer people up. It did not work—the Depression went on, and on, and on. Many Americans never got over the shock.

President Herbert Hoover was elected by a landslide in 1928. He was a brilliant engineer and an experienced manager well-versed in economic realities. Aside from wartime, however, the United States government had never faced a crisis of such magnitude, although the economic recessions that began in 1837, 1873 and 1893 may have provided a glimpse. Because government’s traditional relationship with business had always been one of laissez-faire, tempered by the Progressive Era’s relatively mild regulation, many people could not envision the government providing solutions for problems that government had not apparently caused.

President Hoover had been responsible for the food production program during the Great War, and his efforts in saving the Belgians from starvation had been recognized far and wide. Now, however, Hoover found himself in a position that seemed hopeless, and in which the government itself seemed helpless. President Hoover did not do nothing, however. The actions he took were unprecedented, far more than government had ever taken before in interfering with the affairs of private business. But he still believed in the principle of laissez-fair, and was confident that America could work itself out of its own economic doldrums. He reasoned that the country's economy had to be strong enough to recover with the limited support he was willing to provide. It simply was not enough.

President Hoover’s conservative nature led him to oppose direct financial relief to the unemployed. His program of relief called for the federal government to coordinate local and regional efforts of voluntary agencies in order to “preserve the principles of individual and local responsibility.” He requested federal spending on public works projects and created relief organizations at the national level headed by federal officials. In 1932 he encouraged Congress to create the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to extend loans to banks and railroads, which he hoped would reverse the tide of deflation. He also signed the Relief and Reconstruction Act to provide loans for construction and a Federal Home Loan Bank Act that provided home mortgages for individuals. President Hoover’s actions, however, amounted to far too little to stem the tide of depression that was sweeping across the country.

President Hoover sincerely believed that the American capitalist economic system was strong enough to work its way out from under the crisis. Like many conservatives, he believed that too much government interference would lead the country toward socialism. Furthermore, The Bolshevik Revolution had led to  the Communism that engulfed Russia, sending shockwaves around the world. Socialist parties were strong all across Europe, but America had been through a Red Scare; labor agitation and hints of “socialistic solutions” were seen by many as un-American, unnecessary, even dangerous. The income tax was relatively new, and government revenues were ample for most needs. But the burden of caring for the unemployed and unemployable soon became so large that local, state, and national government, let alone charitable organizations, lacked funds to deal effectively with the problem. As wages and incomes fell, raising taxes hardly seemed the solution.

the Communism that engulfed Russia, sending shockwaves around the world. Socialist parties were strong all across Europe, but America had been through a Red Scare; labor agitation and hints of “socialistic solutions” were seen by many as un-American, unnecessary, even dangerous. The income tax was relatively new, and government revenues were ample for most needs. But the burden of caring for the unemployed and unemployable soon became so large that local, state, and national government, let alone charitable organizations, lacked funds to deal effectively with the problem. As wages and incomes fell, raising taxes hardly seemed the solution.

In some parts of the country people were less affected than in others. People still went to the movies, listened to the radio, played golf and tennis, took vacations, and went about their lives as though nothing was wrong. They tried to ignore the desperate looks of people they often passed on the streets, sitting on benches, too proud to beg, but still hoping for a handout of a dime or a quarter that might buy a sandwich and a cup of coffee.

To make things worse, the middle of the United States went through an era known as the dust bowl; as farmlands dried up, primitive irrigation projects were unable to keep the crops growing. Farmers discovered that with the falling prices they could not earn enough from the sale of their produce to cover the costs of getting it to market. They burned their corn to keep warm, slaughtered their livestock for their own food, and dumped milk in the streets to protest falling prices.

Hoovervilles. Herbert Hoover was not responsible for the depression, although the policies of his Republican predecessors could be cited as contributory factors. While his actions as president went beyond any previous attempts to stimulate economic recovery, he still bore the brunt of the blame for the conditions that deepened during his administration. All over the country people who had been evicted from their homes or who could no longer afford to pay rent, gathered on the outskirts of towns and cities where they constructed shacks out of scrap wood, metal, or cardboard. They lived in tents, abandoned buildings or cars and empty drainpipes. Most of these “Hoovervilles,” as they were called, lacked sanitary facilities or running water. Charitable workers often set up soup kitchens nearby, and residents who were skilled in the building trades did what they could to improve conditions.

Hoovervilles were to be found in all parts of the country; one of the largest was in New York City’s Central Park. Thousands of people were camped along the Hudson River in the area alongside the Hudson River beneath the George Washington Bridge. Although attempts were made to remove Hoovervilles where people were camped on private property, they were generally seen as necessary or unavoidable, and the residents were left to make do as best they could.

The Bonus Army. Many of those who suffered were veterans of the World War I, who had been promised bonuses for their service and had been issued certificates in 1924. Those certificates did not mature, however, for 20 years. In June, 1932 the veterans were organized by a former Army sergeant, and thousands marched on Washington to protest and demand immediate payment. They lived in a Hooverville constructed along the Anacostia River. The veterans constructed facilities, laid out streets, held parades and protested in front of the Capitol. In July Attorney General William Mitchell ordered police to clear out the Bonus Army encampment. President Hoover then ordered the army to complete the evacuation, and troops under General Douglas MacArthur and Major George S. Patton moved against the protesters with fixed bayonets. General MacArthur continued the assault against the Anacostia camping site. Hundreds of veterans were injured and a number were killed. During President Roosevelt’s first administration, the veterans were offered jobs in various New Deal programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps, and eventually the bonuses were paid.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. One additional government act during the Hoover administration was passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff. Although economists have reached differing opinions on the effects of the act, it is generally felt that the tariff contributed to the worldwide depression. During the 1928 campaign, Republicans had promised to assist farmers by raising tariffs on agricultural products. Although Hoover objected to some provisions of the bill and feared that it would lead to retaliation, he signed it because of strong backing by congressional Republicans. Although the short-term effects seemed to aid the U.S. economy, the effects of the act were felt in many countries, and retaliatory tariffs and shifts in trading practices followed, as President Hoover had feared. The failure of a large Asuch as the Civilian Conservation Corps,ustrian bank has been blamed in part on the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. Although Senators Smoot and Hawley were both defeated in the 1932 elections, the damage was done.

The New Deal Spirit

Most Americans know the phrase from FDR’s first inaugural address, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” But in addition to those encouraging words, his address contained much more, much of it couched in words that evoked military action:

I am prepared under my constitutional duty to recommend the measures that a stricken nation in the midst of a stricken world may require. These measures, or such other measures as the Congress may build out of its experience and wisdom, I shall seek, within my constitutional authority, to bring to speedy adoption.

But in the event that the Congress shall fail to take one of these two courses, and in the event that the national emergency is still critical, I shall not evade the clear course of duty that will then confront me. I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis—broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.

That last sentence earned the loudest applause from the inauguration crowd. Serving under President Woodrow Wilson during the Great War, Roosevelt had watched President Wilson organize the economy to meet the emergency of World War I. In 1933 Franklin Roosevelt came to Washington determined to use government to organize the economy again. This time he would deploy government power against the enemies caused by the Great Depression: unemployment, poverty, and hopelessness. His goal of easing suffering is understandable for all; his methods remain the source of controversy. Whatever one decides, it is clear that the legacy of the New Deal is still with us in a powerful way.

Link to FDR First Inaugural Address.

Those who knew Roosevelt well found him unfailingly pleasant, optimistic, and good-natured. What came out of Franklin Roosevelt’s White House via his fireside chats, his regular meetings with the press (Roosevelt held more press conferences than any other president before or since), and reports of those who worked with him was a sense that something good was happening. Roosevelt always began his fireside chats with the greeting, “My friends,” and many people had a sense that he was indeed their friend.

Those who knew Roosevelt well found him unfailingly pleasant, optimistic, and good-natured. What came out of Franklin Roosevelt’s White House via his fireside chats, his regular meetings with the press (Roosevelt held more press conferences than any other president before or since), and reports of those who worked with him was a sense that something good was happening. Roosevelt always began his fireside chats with the greeting, “My friends,” and many people had a sense that he was indeed their friend.

As the New Deal progressed, however, Roosevelt’s manner disconcerted some, for in any conversation he always gave the listener the sense that he agreed with or was it least sympathetic to everything his interlocutor had to say. Thus a number of visitors learned the hard way that although Franklin Roosevelt seemed agreeable to their proposals, that did not mean he was necessarily going to follow their suggestions. Yet even as his political enemies found much to criticize—and Roosevelt developed many political opponents on both the right and left—millions of Americans felt that the government was finally hearing their cries for assistance.

Roosevelt was willing to try anything, and some of the New Deal programs fell far short of expectations; indeed, the New Deal did not end the Depression. The huge outpouring of major legislation in the first hundred days of Roosevelt’s administration was unprecedented; but Roosevelt himself knew well that whatever talents he might possess, and whatever programs his administration might devise, not everyone would agree with his approach to government: the problems were too vast and deep. But he gave people hope.

The Hundred Days: FDR in Action

The first one hundred days of Franklin Roosevelt’s administration constitute one of the most remarkable explosions of legislation in the history of the Congress. The long lame-duck session meant that Roosevelt was not inaugurated until March 4. It was the last time that occurred, as the 20th Amendment soon moved inauguration day up to January 20. (The 20th Amendment was known as the “lame duck” amendment. President elect Abraham Lincoln also had to wait four months before he was able to deal with the Civil War in 1861.) Between Roosevelt’s election and inauguration thousands of banks closed their doors; many people had withdrawn their money and stuffed it under their mattresses for safe keeping, which only made matters worse.

President Roosevelt immediately called a special session of Congress to deal with the banking crisis. On March 9 he sent an Emergency Banking Act to Congress, where it was passed and signed by the president on the same day, an extraordinary accomplishment. The act gave the president broad discretionary power to regulate financial transactions, and he immediately called a national bank holiday. The Treasury Department granted licenses for banks to reopen, and the act also prohibited the hoarding of gold, requiring that anyone holding gold or gold certificates turn them in to the U.S. Treasury in exchange for other currency. Then Roosevelt went on the air with his first fireside chat, explaining his actions to the people “in terms even a banker could understand.” His precipitous action checked the money panic.

On March 20 the president signed the Economy Act, which sought to balance the budget by reducing government salaries 15 percent. It also cut private pensions and reorganized government agencies for greater economy; in the end it saved about $243 million. The Democrats had promised an end of Prohibition, and with passage of the 21st Amendment, Congress passed the Beer and Wine Revenue Act of March 22, which taxed alcoholic beverages to raise federal revenue.

On March 31 Congress passed the Civilian Conservation Corps Reforestation Act, which established the Civilian Conservation Corps and provided 250,000 jobs for males ages 18–25. Wages were $30 per month, part of which was to go to dependents. (A family could eat on a dollar a day in those hard times.) Under the act, camps were built and run by different federal departments in order to facilitate conservation projects such as planting trees to combat soil erosion and to improve national forests, as well as creating fish, game, and bird sanctuaries. By 1941 two million young men had served in the CCC, and many of their works still stand in America’s forests.

|

Within less than a month of FDR’s inauguration four major bills were passed, and more were to come. On April 19 the United States officially abandoned the gold standard, which some have called the “most revolutionary act of the New Deal.” This meant that paper money would no longer be redeemable in gold. The value of the dollar soon declined abroad, which stopped the drain of American gold to Europe. The government fixed the value of gold at $35 per ounce, and it became illegal for citizens to own gold, except in jewelry and other artifacts. At the same time the government purchased large quantities of silver, and silver certificates continued to be redeemable in silver, generally coins. (The “Washington Quarter” was mostly silver in content until 1964.) |

Additional measures of the Hundred Days included:

- The May 12 Federal Emergency Relief Act created the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, funded at $500 million, one half of which was to go to the states for direct relief. The remainder was to match state funds for unemployment relief at a rate of $1 for $3. Harry Hopkins was appointed relief administrator.

- Under the leadership of Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace, Congress pulled out all the stops to help farmers, passing the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act, and the Farm Credit Act. The acts provided for the elimination of surplus crops, establishment of parity prices, and the reduction of crop production by paying farmers to allow land to lie fallow. In the process, animals were slaughtered and crops plowed under, which Secretary Wallace himself called a “shocking commentary on our civilization.” Many were outraged that pigs were slaughtered while people were starving, although usable meat was distributed through the FERA. Portions of the Act were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, but amendments and later acts made adjustments to meet the court’s objections.

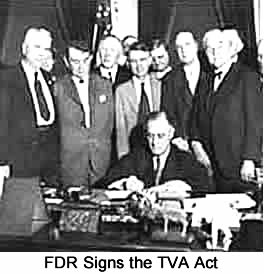

- On May 18 the Tennessee Valley Authority was created as an “experiment” in social planning. The TVA was given authority to build dams and power plants and to develop the entire region economically by selling power for private and industrial uses. The TVA, a pet project of FDR’s, which he visited several times, became a yardstick for evaluating the operation of power companies, establishing fair rates, and so on. Nine dams were built, and existing dams were acquired by the TVA. During World War II power from TVA dams was used to produce munitions and support operations at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which were part of the Manhattan (atomic bomb) Project.

- On June 16 the Banking Act of 1933 (the Glass-Steagall Act) created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which protected all bank deposits up to $5,000 and widened the power of the Federal Reserve Board over member banks. The act separated commercial and investment banking, and forced banks to get out of the investment business, restricting the use of bank deposits for speculative ventures. Today all bank deposits are insured by the FDIC up to $250,000 through December 31, 2013.

- The National Industrial Recovery Act of June 16 created the National Recovery Administration (NRA), probably the most controversial of the New Deal measures. The act established fair trade codes and provided for industrial self-regulation with government supervision. The act included restrictions of plant operations, the establishment of a minimum wage, prohibition against child labor, and limited the work week to forty hours. The NRA symbol was the Blue Eagle—which businesses could display after "Signing the pledge.” The NRA also created the Public Works Administration (PWA), budgeted with $3.3 billion to be spent on public works construction. The primary goals were to provide useful employment, raise purchasing power, promote welfare, and contribute to the revival of American industry.

- Additional acts included new laws to control information on new securities being offered to the public; make paper legal tender; establish a federal employment service to help people find jobs; make loans for people to pay taxes, make repairs on homes, and refinance mortgages; and improve efficiency of railroads by reorganization and creating a federal coordinator of transportation.

That huge outpouring of legislation brought the hundred days to an end, but the New Deal continued to expand government activity throughout 1933 and into 1934 and ’35. Although the New Deal measures were considered radical by many at the time, the social and economic reforms introduced by Roosevelt had been common in Europe for some time. In addition, beginning with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, the government had increasingly adopted policies that tended to soften the effects of laissez-faire capitalism. Progressives led by Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson had continued the process, and the New Deal sustained that trend.

That huge outpouring of legislation brought the hundred days to an end, but the New Deal continued to expand government activity throughout 1933 and into 1934 and ’35. Although the New Deal measures were considered radical by many at the time, the social and economic reforms introduced by Roosevelt had been common in Europe for some time. In addition, beginning with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, the government had increasingly adopted policies that tended to soften the effects of laissez-faire capitalism. Progressives led by Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson had continued the process, and the New Deal sustained that trend.

The most remarkable aspect of the New Deal, especially in its early days, was the speed with which it was put into practice. The legislation produced in the first hundred days of Franklin Roosevelt’s first term was comparable to the entire amount of major business legislation passed during the Gilded Age. Just as remarkable, the New Deal suddenly brought millions of average Americans an awareness of government that they had never had before. The vast programs, along with FDR’s fireside chats, made government a part of people’s daily lives.

Many of Roosevelt’s critics have charged him with creating a welfare state, but Roosevelt continually supported programs designed to put people back to work. The Civil Works Administration, created in November 1933, provided jobs as diverse as ditch digging, making highway repairs and teaching.

The troubles of the American farmer were exacerbated by the great drought that began in 1931, creating what was known as the “dust bowl.” Severe storms blew clouds of dust raised from plowed fields and dried out prairies across the southern Great Plains. The storms destroyed crops and equipment, and people and animals suffered. Close to a million people, sometimes called “Okies,” left Oklahoma and other areas of the Midwest during the 1930s and 1940s and headed for California. (Their trials are chronicled in John Steinbeck’s classic work, Grapes of Wrath.) When the Agricultural Adjustment Act was declared unconstitutional, four additional programs were instituted, and by 1940 millions of farmers were receiving subsidies under federal programs.

Still the Depression lingered on, and the social dislocations resulting from extended periods of unemployment that kept thousands in abject poverty took a grave toll on substantial portions of the population, especially in areas such as Appalachia and in manufacturing regions where heavy industries had been brought almost to a standstill. Marriages were delayed, birthrates plummeted, and a federal bureau determined that approximately 20 percent of all American children were underfed. Armies of men, women, and even children rode the rails and lived in shanty towns in search of employment or any opportunity to improve their poverty-stricken lives.

Responding to the fact that people were still suffering, as well as to his critics, Roosevelt launched what became his Second New Deal. In 1935 Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act, which created the National Labor Relations Board. The act defined unfair labor practices and granted workers the right to bargain collectively through unions. It also prevented business owners from interfering with union matters. The NLRB supervised collective bargaining, administered elections, and ensured workers the right to choose their own union.

The most long-lasting and, according to Roosevelt, most important product of the New Deal was the Social Security Act of 1935. The act was a government insurance program for aged, unemployed, and disabled persons based on contributions by employers and workers. Critics complained that the Social Security system violated American traditions and might cause a loss of jobs. Although payments are made by the federal Social Security Administration, they are funded by payroll taxes on wages, which are paid by workers and their employers. Initial benefits were quite modest, ranging from $10 to $40 per month. Today, however, Social Security is one of the largest and most far-reaching programs administered by the federal government.

Although Social Security was never designed to be a full retirement system, many people have come to see it as just that, and attempts to modify or reform Social Security are generally met with strong opposition. As the baby-boom (post-World War II) generation approaches retirement, fears exist that payments made into the system will be insufficient to keep pace with the expanding aging population, although the age for collecting benefits has been raised in recent years. Thus a measure of the persistence of the New Deal’s legacy is the fact that Social Security is still central to the ongoing political debate in the country. Lobbying groups such as the AARP have kept the issue in the public eye.

Another important component of the Second New Deal was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which over the course of its lifetime built hundreds of buildings, bridges, roads, airports, schools, and other public buildings such as post offices. By the time it ended during the Second World War, more than 9 million people had been employed by the WPA. Cornerstones of many buildings still in use bear the WPA imprint. In order to raise more revenue, Congress also passed the Revenue Act of 1935, which became known as the “Soak the Rich Act.” It raised tax rates on higher incomes, but did little to increase federal tax revenue, and it did not significantly redistribute income, which was a goal of the Second New Deal.

FDR Critics Left and Right. The massive injection of government funds into the economy did not end the Depression, though many of the programs brought temporary relief to thousands of people, and Roosevelt’s confident demeanor did give people hope. For a time it seemed as if every step forward would bring a reaction from businessmen and other conservatives, and critics on both the right and the left attacked FDR with increasing frequency. Roosevelt critics included men such as Father Charles Coughlin, a conservative Roman Catholic priest whose weekly radio show was heard by millions of listeners. Father Coughlin had initially supported the New Deal, but then became increasingly critical of the administration’s failure to institute reforms.

Another vigorous anti-Roosevelt activist was Dr. Frances Townsend, who created a plan calling for all persons over sixty years of age to get $200 per month if they promised not to work; they would have to spend it within thirty days. Financing would come from a 2 percent national sales tax. Townsend Clubs eventually reached a membership of 2 million Americans, and in 1936 his followers aligned themselves with the Union Party.

Another vigorous anti-Roosevelt activist was Dr. Frances Townsend, who created a plan calling for all persons over sixty years of age to get $200 per month if they promised not to work; they would have to spend it within thirty days. Financing would come from a 2 percent national sales tax. Townsend Clubs eventually reached a membership of 2 million Americans, and in 1936 his followers aligned themselves with the Union Party.

The most formidable opponent of Roosevelt, however, was Senator Huey P. Long, the former populist governor of Louisiana. Rising from an impoverished background, Long was a self-made politician who quickly became a legend in his own time. Struggling against conservative Louisiana Democrats, Long was willing to invest heavily in programs for the state. He oversaw construction of thousands of miles of roads and provided free books for schoolchildren. He also helped convert Louisiana State University into a fine institution of learning and added a medical school to its programs. In addition he strengthened the economic foundations of the city of New Orleans by providing for additional infrastructure.

Long’s motto was “Every Man a King”; his nickname was “The Kingfish.” Although he had supported Governor Roosevelt’s bid for the presidency in 1932, he became disenchanted when he felt that Roosevelt was not moving far enough to the left. He began to see FDR as a front man for capitalists and started attacking him. (FDR reportedly declared that Huey Long was “one of the most dangerous men in America.”) Long came up with a plan called “Share Our Wealth”; in essence the idea was to tax estates and incomes in excess of one million dollars up to a rate of 100 percent and to guarantee to every American a home, an automobile, and an education through college. Long might have given Roosevelt serious trouble in the election of 1936, though it’s unlikely he could ever have won, but he was assassinated in 1935 by a disgruntled physician.

Huey Long was portrayed as the character Willie Stark in Robert Penn Warren’s classic novel All the King’s Men. A film based on the novel won the Academy award for best picture in 1949, and a recent version (2006) stars Sean Penn as Huey Long.

A New Deal for the Indians

In 1924 all American Indians were granted American citizenship. For over a century the development of Indian and white relations had centered around one basic dilemma: Should the Indians be “Americanized” and separated from their cultural surroundings to become everyday American citizens? Or should the Indians be encouraged to remain on reservations or in other protected areas so that they could continue to live according to their cultural traditions? The answer, of course, is that for much of American history, Indians have followed both paths. Some have become assimilated, and some have resisted assimilation. The topic remains controversial within Indian cultures, and it must be kept in mind that existing American Indian cultures are still quite diverse today. (As of 2006 there were 562 federally recognized American Indian Tribes in the United States.)

An example of a cultural issue that reflects Indian diversity is the ongoing debate over Indian “mascot” names. Many tribes object to the use of Indian names or symbols by athletic teams. On the other hand, the Seminole Tribe in Florida has no objection to the use of their name by Florida State University. As is true with most cultural issues, there are various sides to the story.

Many people assumed that the granting of citizenship to Indians would complete the process of assimilation. But many Indians continued to live on reservations and were more dependent than ever upon the government for much of their welfare. Forced assimilation had proved destructive to Indian cultures and did not provide a suitable economic basis upon which Indians could live their lives.

Franklin Roosevelt appointed Indian reformer John Collier as Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian affairs. Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes said, “Collier was the best equipped man who ever occupied the office,” as Collier had worked as an Indian reformer for some time and was familiar with many of the problems of Native American culture. Collier hoped to be able to preserve Indian culture and heritage and resolve the complicated issues of Indian lands and Indian government.

In 1934 Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), which reversed the Dawes Act of 1887 that had divided Indian land among private owners and restored tribal ownership. Along with the IRA, Collier used various other New Deal programs to assist the Indians, including the Public Works Administration and the Civil Works Administration. He established an Indian Civilian Conservation Corps, and oversaw the construction of schools and hospitals as well as various training programs. Collier continued to work for the acquisition of new land for Indians and to establishment self-government for those tribes who lived on reservations. He continued his services throughout World War II, finally resigning in 1945. Accepting Collier’s resignation with regret, FDR praised his services and commended him for having reoriented government policies toward the Indians.

Most observers feel that John Collier's motives were of the highest and that he sincerely wanted to help the Native American populations, but more recently a number of historians have criticized the IRA and Collier's administration of it on various grounds. Tribal leaders, for example, have charged that federal programs are just heavy-handed ways of trying to control Indians. At present the federally recognized tribes have a formal relationship with the U.S. government, referred to as a government-to-government relationship, based on the fact that the organized Indian tribes living on reservations now possess a sovereignty that is higher than that of the states. In addition to relationships with the federal government, many tribes have special relationships with the states in which they are located.

Generally, the governing authority on Indian reservations is the tribal government. That means, for example, that if one is on the Navajo reservation in Arizona, one is subject to Navajo law. Indian governments on reservation areas include the full spectrum of generally recognized government agencies, from presidents or chief executives to legislative bodies, courts, administrative and police agencies.

The next section with cover Franklin Roosevelt's second term, 1937-1941. It would not proceed nearly as smoothly as his first term. Despite the enormous achievements of his first four years, critics would begin to emerge, from the Supreme Court, to conservative Democrats and other vocal critics on both the left and right. Before his second term was over, war would break out in Europe once more, and the president and the nation would have to shift their attention from domestic to international affairs. But before that could begin, Roosevelt would have to be reelected.

| Interwar Years Home | Twenties Home | Depression Home | New Deal Home | Updated October 29, 2021 |