In addition to the development of the railroads, discussed in the previous section on the development of the American West, other new industries that transformed American life in unprecedented ways proliferated. The changes that took place in the course of the 19th century, and in particular the period between the end of the Civil War and 1900, had a transforming effect unseen since the days of the Roman empire. Only the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg had a comparable impact on the lives of huge segments of the population. The Industrial Revolution was not limited to America, of course, as all the major developed nations across Europe and Asia benefited enormously from the changes. But the growth of industry in America outstrip the progress of much of the rest of the world.

If a farmer living in 1500 had suddenly been transported to the year 1800, he might have noticed some changes, but they would hardly have been startling. Most labor was still accomplished by human muscle and animal power; ships were propelled by wind and sails; and transportation, even over modest distances, was measured in days or weeks, not hours. But if you took a farmer or artisan from 1800 and set him on the ground in 1900, the visible changes would no doubt have overwhelmed him.

Although we cannot imagine life in the year 2100, it must be said that the 19th century was the century of the greatest change in the history of man. True, the airplane, spaceship and atomic bomb were products of the 20th century, but those inventions were not unimaginable in 1900, and they did not have the overwhelming impact of, for example, the train powered by a locomotive that forever changed man's appreciation of the concept of time. When the first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858 and Queen Victoria exchanged a message with the President James Buchanan of the United States, people thought a miracle had been wrought.

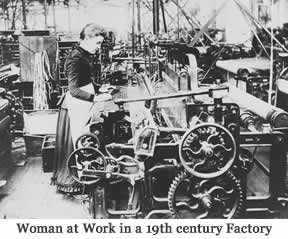

The accelerating rate of change between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the century was truly astounding. The inventions of Thomas Alva Edison, the entrepreneurial genius of Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Carnegie, and the contributions of thousands of other imaginative men and women changed daily life in America. Often the change was for the better, but sometimes it was for the worse. In 1820 the factory had been a small, family-oriented business with perhaps a dozen employees. The textile mills of New England were larger, as were the ship yards along the Atlantic Coast, but in most businesses the owner was also the manager, and he knew the name and something of the life of everyone who worked for him.

By 1880 factories were employing hundreds, even thousands of workers. Owners and upper-level managers rarely saw their workers on a day-to-day basis and had little concept of life in their factories. But the advances were impressive: the light bulb, high-grade steel, mechanical devices of all sorts, mass production, the skyscraper, electric power, internal combustion engines, the transcontinental railroad, canned food and ready-made clothing, indoor plumbing, artificial lighting, and countless other advances transformed the lives of those who could afford to take advantage of such things.

At the lower end of the economic scale, life did not necessarily get better. As millions of immigrants poured into the country, cheap labor was the norm. While workers attempted to organize themselves for better pay and working conditions, they knew that the hordes of immigrants pouring through Ellis Island and other ports of entry were eager to displace them, even at wages scarcely enough to live on. As machines took over much of the process of manufacturing, workmanlike skills often became irrelevant, eliminating much of the need for skilled labor. A man might stand all day pulling a handle or turning a valve or doing some other mindless, repetitive task, which meant that he could be replaced in minutes should he suffer an injury or illness.

At the lower end of the economic scale, life did not necessarily get better. As millions of immigrants poured into the country, cheap labor was the norm. While workers attempted to organize themselves for better pay and working conditions, they knew that the hordes of immigrants pouring through Ellis Island and other ports of entry were eager to displace them, even at wages scarcely enough to live on. As machines took over much of the process of manufacturing, workmanlike skills often became irrelevant, eliminating much of the need for skilled labor. A man might stand all day pulling a handle or turning a valve or doing some other mindless, repetitive task, which meant that he could be replaced in minutes should he suffer an injury or illness.

As the cities rose and bridges, rail lines, and port facilities expanded, the progress was visible everywhere, even if thousands were too tired or absorbed in their own misery to notice. Large businesses required clerks, accountants, and other white-collar workers, and the new middle class prospered as never before. The weekend, usually consisting of a free half-day on Saturday and all day Sunday, gave workers a chance to rest. As the workday shortened and leisure time increased, the abundance of cheap newspapers and magazines provided endless sources of information for the literate and curious. Schools and universities expanded dramatically. Among very poor people, however, children were often sent to the factory rather than to school, and truant officers often roamed the halls of the factories, driving students back to the classroom. In many cases, the parents would tell the children to return to their places of work as soon as possible; every family member had to produce income if the poor family was to survive and prosper.

See Also “The War Between Capital and Labor”

Even in those harsh conditions, reforms were underway. The status of the working man was recognized when the first Labor Day was celebrated on Tuesday, September 5, 1882, in New York City. The paid summer vacation became an expectation for many middle-class workers. Although health insurance, unemployment insurance and accident benefits did not evolve fully until the Progressive Era, millions of Americans found life easier and more pleasant than they had during the early 19th century.

Industrialization in America, slow to start because of the Civil War, took off during the last half of the 19th century, so that by the year 1900 American steel production had far outstripped that of the rest of the world. The United States had over 200,000 miles of railroads by 1914, about as many miles as the rest of the world combined. Tons of American farm products and manufactured goods were shipped abroad in a growing American fleet of steam-powered merchant vessels, and wealthier American travelers toured the globe in search of interesting spectacles.

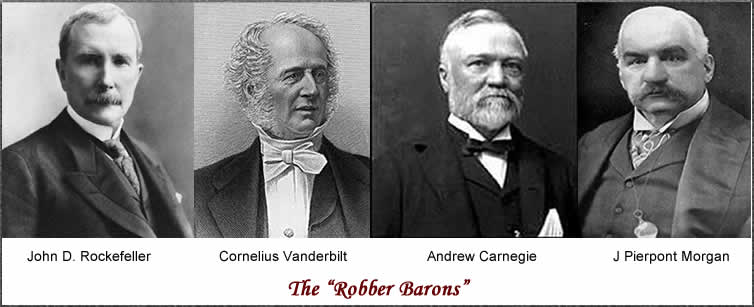

Capitalism in the Gilded Age. The period between the end of the Civil War and 1900 is rightfully called The Gilded Age, because for many people in America and around the world, it seemed as though everything they touched turned to gold. But the term gilded has a special meeting in that regard. For when an object is covered with gold or gold leaf, the substance underneath may not shine as brightly or indeed at all. For while many in the upper echelons of society were becoming wealthy beyond their wildest expectations, many others were suffering. So many of these wealthy businessmen and financiers became called robber barons--they were accused of robbing from the poor to line their own pockets with gold. On the surface, that judgment seems fair; but in fact, things were not that simple. There is no question that many of the wealthy men of the type pictured above, plus many others, were guilty of what was known at the time as sharp practice. They took advantage of every loophole in the law, but in fact there were few laws to control what they did.

It should be remembered, however, that the period was also known as the age of Social Darwinism. Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, and as knowledge of his work spread, it was adapted from his evolutionary view into the social Darwinist philosophy. The idea was that as species evolved over time, the strongest survived and prospered, while the weakest died out. There was nothing about that that seemed malevolent; it is been estimated that over the course of time since the first life appeared on this planet 99% of all organisms have disappeared.

That general understanding lead people to argue that what was good in the biological world might be equally valid in the social milieu. In other words, in any given society, what was wrong with the stronger human beings prospering and surviving while those who are less fit died out. Wouldn't that actually improve the entire human race? The theory was even taught in colleges, and one famous professor was asked if he ought to survive if a lecturer came along who proved superior to his techniques. His answer was that of course the stronger one should prevail, even if it cost him his career. That was a harsh judgment, but nobody questioned its validity at the time. To claim that that idea no longer prevails in the world today ignores the fact that there are still vast disparities between the most successful, wealthiest and prosperous elements of society and those who are less fortunate, even those who may consider themselves quite comfortable. It is estimated today that in the United States 40% of the wealth in the country belongs to the top 1% of the population. It might therefore be fair to say that Social Darwinism has not died.

So what are we to make of these so-called robber barons? Each one of them has his own story, and a multitude of literature is available on all the figures shown above as well as many others. Not all wealthy men fit into that category. Milton S Hershey, for example, founded the famous candy company, not only treated his workers well; in the town he built that became Hershey, Pennsylvania, he provided comfortable living accommodations for his workers, and later found in an orphanage to take care of parentless children. Although also guilty of some practices that might be called "sharp," such as sending his employees to some of the famous Swiss chocolate manufacturers to learn their secrets, nothing he did reached the level of the practices of some of his fellow businessmen.

In addition, the robber barons were in many cases known for their good works. As we discuss each one of them, their contributions to society will be included. Some of their names, of course, are associated with the works they created. Carnegie Hall in New York City and Carnegie libraries all over the country were created by Andrew Carnegie, the steel baron. He was of the opinion that those who became wealthy should put that wealth to work in the service of mankind. He argued that his fellow millionaires should follow his example. We will address the success of that notion with several of these famous businessmen.

The “Robber Barons”

Back in the time of Thomas Jefferson, the enemies of freedom included what he and his fellow Republicans called the “aristocracy.” By that he meant monarchists, men of the British upper class (and their American imitators) who wielded unrestrained power. In other words, unbridled government. By the latter part of the 19th century, a new aristocracy had arisen in America—the “great captains of industry.” Those industrialists, bankers, traders, merchants and their ilk were called the robber barons, and the only power sufficient to rein them in was government. So Jefferson's enemy of freedom—big government—became the means of protecting the people from the monied aristocrats.

|

Capitalism in the Gilded Age. The period between the end of the Civil War and 1900 is rightfully called The Gilded Age, because for many people in America and around the world, it seemed as though everything they touched turned to gold. But the term gilded has a special meeting in that regard. For when an object is covered with gold or gold leaf, the substance underneath may not shine as brightly or indeed at all. For while many in the upper echelons of society were becoming wealthy beyond their wildest expectations, many others were suffering. So many of these wealthy businessmen and financiers became called robber barons--they were accused of robbing from the poor to line their own pockets with gold. On the surface, that judgment seems fair; but in fact, things were not that simple. There is no question that many of the wealthy men of the type pictured above, plus many others, were guilty of what was known at the time as sharp practice. They took advantage of every loophole in the law, but in fact there were few laws to control what they did.

It should be remembered, however, that the period was also known as the age of Social Darwinism. Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, and as knowledge of his work spread, it was adapted from his evolutionary view into the social Darwinist philosophy. The idea was that as species evolved over time, the strongest survived and prospered, while the weakest died out. There was nothing about that that seemed malevolent; it is been estimated that over the course of time since the first life appeared on this planet 99% of all organisms have disappeared.

That general understanding lead people to argue that what was good in the biological world might be equally valid in the social milieu. In other words, in any given society, what was wrong with the stronger human beings prospering and surviving while those who are less fit died out. Wouldn't that actually improve the entire human race? The theory was even taught in colleges, and one famous professor was asked if he ought to survive if a lecturer came along who proved superior to his techniques. His answer was that of course the stronger one should prevail, even if it cost him his career. That was a harsh judgment, but nobody questioned its validity at the time. To claim that that idea no longer prevails in the world today ignores the fact that there are still vast disparities between the most successful, wealthiest and prosperous elements of society and those who are less fortunate, even those who may consider themselves quite comfortable. It is estimated today that in the United States 40% of the wealth in the country belongs to the top 1% of the population. It might therefore be fair to say that Social Darwinism has not died.

So what are we to make of these so-called robber barons? Each one of them has his own story, and a multitude of literature is available on all the figures shown above as well as many others. Not all wealthy men fit into that category. Milton S Hershey, for example, founded the famous candy company, not only treated his workers well; in the town he built that became Hershey, Pennsylvania, he provided comfortable living accommodations for his workers, and later found in an orphanage to take care of parentless children. Although also guilty of some practices that might be called "sharp," such as sending his employees to some of the famous Swiss chocolate manufacturers to learn their secrets, nothing he did reached the level of the practices of some of his fellow businessmen.

In addition, the robber barons were in many cases known for their good works. As we discuss each one of them, their contributions to society will be included. Some of their names, of course, are associated with the works they created. Carnegie Hall in New York City and Carnegie libraries all over the country were created by Andrew Carnegie, the steel baron. He was of the opinion that those who became wealthy should put that wealth to work in the service of mankind. He argued that his fellow millionaires should follow his example. We will address the success of that notion with several of these famous businessmen.

John D. Rockefeller arose from a position of bookkeeper to create the Standard Oil Company in 1870, becoming in the process the richest man in the world and America’s first billionaire. Ruthless in his business practices, he drove smaller oil companies out of business by accepting short-term losses in the sale of kerosene and other products, undercutting the prices of competitors. By 1904 Standard Oil controlled about 90% of the oil business in the United States and had large investments overseas. (See Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., (New York, 1998.)

See More on “Rockefeller: The Richest Man in the World”

Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt started working at age 11 as a deck hand on his father’s ferry boat on the Hudson River. In due course he became owner of his own boat and was soon engaged in the lucrative Hudson River traffic between New York and Albany. With the profits he made from his boat business he began to invest in railroads in the 1830s, eventually owning a number of lines that merged into the Grand Central Railroad, which operated between New York City and Chicago.

Andrew Carnegie started working in a factory at age 13 for twelve hours a day, six days a week, for about two dollars a week. Bright, industrious, and a voracious reader, Carnegie was the epitome of the self-made man. From his job as a telegraph operator for the Pennsylvania Railroad, he rose in the company and became more widely engaged in the railroad business. With the capital he accumulated, in the years after the Civil War Civil War he turned his attention to the production of iron goods. By creating profitable partnerships and investing widely and wisely, he eventually saw his Federal Steel Company become the core of the United States steel Corporation, the first billion-dollar industry in the world.

Later in life Carnegie turned to philanthropy, funding educational and cultural facilities, including over 3,000 libraries in 47 states and around the world. He funded the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh and Carnegie Hall in New York City. By the time of his death Carnegie had bequeathed several hundred million dollars, the equivalent of over $4 billion in current terms. He also encouraged his fellow millionaires to meet the responsibilities that accompany the accumulation of wealth, suggesting that it was wrong for a person to die rich.

Management of the huge sums of money needed to form and operate the giant corporations of the industrial era required skillful financiers. J. Pierpont Morgan began work in his father's London bank in 1857. He soon moved to America, where he worked at various investment banks, eventually becoming founder of J.P. Morgan & Company. He was the driving force behind the rise of the House of Morgan, an international entity that became one of the most powerful instruments of commerce and diplomacy in history.

Seen by many observers as arrogant and overbearing, J.P. Morgan orchestrated many of the biggest financial deals of the industrial era, such as the creation of United States Steel. He used his financial power to gain control of railroads and other industries. Morgan also had a huge impact on national and international financial affairs, as the Morgan Bank often served as an adjunct to the United States Treasury. He spent lavishly on works of art, eventually leaving much of his collection to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Although not as wealthy as some of the industrialists of that gage, he nevertheless controlled billions of dollars. (See Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance, New York, 1990.)

All those men and dozens of others like them exercised an extraordinary degree of control over the commercial life of the United States. Their interests interlocked; bankers and industrialists frequently shared seats on each other’s boards of directors, so that the interests of the many contributed to the wealth of the individual corporations. They exercised substantial control over governments, often coming to the rescue in times of financial crisis by pumping dollars or gold into the financial arena. Political leaders frequently used institutions like the House of Morgan to finance government operations and perform diplomatic functions, both in peace and war. In many ways the large corporations exerted more power over the state of the nation that did the government, sometimes for good, often for the benefit of none but themselves.

Thomas Alva Edison started work as a telegraph operator. His technological skills eventually led to the award of over 1000 patents for his own inventions. Best known for his incandescent light bulb, recording and motion picture machines, he was also a successful businessman who was instrumental in creating America’s first network of power companies. His famous laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, was frequently the scene of discussions between Edison and other industrialists such as Henry Ford. He is famous for his maxim, “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.”

Thomas Alva Edison started work as a telegraph operator. His technological skills eventually led to the award of over 1000 patents for his own inventions. Best known for his incandescent light bulb, recording and motion picture machines, he was also a successful businessman who was instrumental in creating America’s first network of power companies. His famous laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, was frequently the scene of discussions between Edison and other industrialists such as Henry Ford. He is famous for his maxim, “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.”

All those men and dozens of others like them exercised an extraordinary degree of control over the commercial life of the United States. Their interests interlocked; bankers and industrialists frequently shared seats on each other’s boards of directors, so that the interests of the many contributed to the wealth of the individual corporations. They exercised substantial control over governments, often coming to the rescue in times of financial crisis by pumping dollars or gold into the financial arena. Political leaders frequently used institutions like the House of Morgan to finance government operations and perform diplomatic functions, both in peace and war.

Monopolies, Trusts, Pools and Corporate Integration

In an age of fiercely competitive practices, businesses sought means of controlling markets in order to maximize profits. The most obvious way to influence the market was to create a monopoly. When a corporation achieves monopolistic status, it is large enough to dominate the market for the products it makes, thus being able to control prices. A monopoly does not have to control the entire market; economic theory suggests that once a corporation has about a one third share of the market, it has become monopolistic. In modern times, however, the rise of a global economy and international competition has influenced the way individual nations view monopolistic practices. (A close examination of the Microsoft Corporation revels how the issue of monopoly control plays out in more modern times.)

Monopoly control of markets was achieved by the organization of trusts. The standard oil Company offers an example. Between 1868, when the first Standard oil company was founded in Pennsylvania, and 1900, Rockefeller's Standard Oil Corporation brought other companies under its control, some of which were founded by Rockefeller himself. Standard oil companies existed in Ohio, Iowa, New Jersey, California, and elsewhere. Standard also gained control of competing companies such as Atlantic Refining, Acme Oil Company and others. By 1900 the Standard Oil Trust exercised near full control over the oil industry in the United States.

Less formal monopolistic practices included the creation of pools, which consisted of companies that were not legally organized together but nevertheless entered into agreements to control market share, pricing, distribution and so on.

Yet another means by which corporations sought to increase profits was through integration, both horizontal and vertical. Horizontal integration was similar to the formation of trusts, except for the fact that this practice involved the simple takeover of smaller competing companies rather than leaving them technically under separate management. Standard Oil would open new outlets in areas they had not yet reached, sometimes undercutting local companies until they folded or sold out to Standard.

Vertical integration involved a corporation's expanding its operations both up and down the production chain from the procurement of raw materials to the actual retail sale of products. In the steel industry, vertical integration would involve the acquisition of sources of coal and iron ore, the basic raw materials needed for the creation of steel. A company such as Carnegie Steel also acquired fleets of ore boats to move raw materials on the Great Lakes. Oil and steel companies also built railroad spurs, sometimes to avoid the monopolistic practices of their carriers. In the oil business, vertical integration might involve creating a chain of gas stations or businesses that would sell kerosene and other petroleum products direct to the public.

Until the government was able to organize the means to control such practices, corporations in the steel, oil, tobacco, meatpacking, and other industries struggled to control their respective markets. The only restrictions on their predatory practices came from competitors, and when they were eliminated, the giant corporations were able to dictate conditions for the marketing of their products. (The Interstate Commerce Act and Sherman Antitrust Act will be discussed below.)

Certainly the wealth of men like Carnegie provided the wherewithal for philanthropy, which in turn brought great benefits to the American people in the form of universities, hospitals, libraries, museums, parks, and countless other contributions to American society and culture. Advances in science, medicine and the arts were financed through the generosity of those captains of industry and finance. John D. Rockefeller funded medical research to attack chronic disease that plagued poorer segments of society. He also gave generously to Spelman College in Atlanta, an elite college for Black women named in honor of Rockefeller’s wife, Laura Spelman. Despite their well-publicized public generosity, their callous disregard for the plight of those they exploited made the Robber Barons pariahs in the minds of the public. They built great institutions, amassed great wealth, did much good and much harm. Individually and collectively they have been studied in detail. Among the noteworthy industrialists:

- Andrew Carnegie: Railroads and Steel

- John D. Rockefeller: Oil

- Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt: Shipping and Railroads

- John Jacob Astor: Real Estate and Fur

- Henry Clay Frick: Steel

- Jay Gould and James Fisk: Railroads and Finance

- Andrew Mellon: Finance

- Leland Stanford: Railroads

- John Pierpont Morgan: Finance

- Collis P. Huntington: Railroads

- Charles Crocker: railroads

- George Mortimer Pullman: Railroads

- Thomas Alva Edison and the Business of Invention: Edison is not generally included in the category of “robber barons,” but his name should be included among the industrial giants of the Gilded Age.

(See Charles R. Morris, The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould and J.P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy, New York, 2005.)

| Gilded Age Home | American West | Capital and Labor | Politics | Updated January 20, 2018 |