The War Between Capital and Labor

Because we live in an age in which workers are protected by federal and state laws as well as by sound business practices, it is hard for us to imagine a time when workers—especially unskilled, often immigrant workers—were completely at the mercy of their employers. (The plight of many illegal immigrant workers today may be comparable; however, without legal status, they have little recourse to assistance in case of unfair practices.) As we mentioned above, before the industrial age factories and workplaces were small enough that the owner knew everyone by name and often worked alongside his or her employees. The age of the modern factory and impersonal management changed all that, and the patent unfairness with which workers were treated became scandalous. For example, if a worker was injured on the job by faulty machinery, there was no mechanism for obtaining compensation. If a worker sued, he or she had to prove that it was not his or her own negligence that caused the accident. It is very difficult to prove a negative in such circumstances.

Historian Page Smith examines the industrial revolution in Volume 6 of his People's History of the United States and calls the events of that era “The War between Capital and Labor.” It is an apt title: the two sides were indeed at war, with armies of armed men fighting on both sides. The level of human violence and destruction of property did in fact often create warlike conditions, a situation exacerbated by the fact that many workers were Civil War veterans. They declared themselves just as prepared to shoot a corporate hireling as they had been ready to kill a Yankee or a rebel. America’s captains of industry, who themselves often rose from very modest circumstances, saw workers as commodities to be dealt with like any raw material. Cold, ruthless, calculating and impervious to the negative effects of what they were doing, they hired their own armies to deal with recalcitrant laborers. (See Page Smith, A People’s History of the Post-Reconstruction Era: The Rise of Industrial America, New York, 1984, p. xiii.)

The Workers

The worker in the Western World has a troubled history. Thomas Hobbes described life in nature as poor, solitary, nasty, brutish, short—and for many workers that was the case. Various political theories attempted to explain or find solutions for the plight of the working classes. Socialists saw evil as an inevitable result when capitalism was left to its own devices; Liberalism called for freedom from oppression, first from government, then from business; Communism—Marxism and Leninism—saw the history of man as the history of class struggle. Of those theories, Communism was the most attractive to the mass of workers who labored in daily to make America wealthy, but who controlled few of the benefits of that wealth. The ultimate goal of Communism was labor ownership of the means of production and a state run by the proletariat, theoretically in a classless society.

Classical economists saw labor as commodity, to be bought and sold according to market demands, and were pessimists about hopes for the working poor. Adam Smith held government intervention harmful and advocated international division of labor. Thomas Malthus argued that the immediate plight of the working class could only become worse because of population growth. David Ricardo formulated the “Iron Law of Wages”: If wages are raised, more children will be produced; they will go into the market place and reduce the value of labor. The result will be that fewer children will be born, wages will rise, and the cycle will repeat. Thus wages always work toward minimum level. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels posited the theory that class struggles lead to oppression, as they outlined in the Communist Manifesto of 1848. Marx’s sister, Eleanor Marx Aveling, and her husband traveled the U.S. and reported on labor conditions. Marx saw slavery in the South as a logical extension of capitalism. (Marx wrote for the New York Tribune during the American Civil War.) Working against the idea of reform was the notion of “social Darwinism.” If survival of the fittest operated successfully in nature, then was it not correct that only the fittest should survive in society? Such ideas served to suppress movements to improve the lives of the working classes. (The concept of Social Darwinism is discussed further below.)

Andrew Carnegie expressed bitterness about the war between capital and labor. He saw the move toward cooperation as opposed to competition as “the destruction of individualism, private property and the law of accumulation.” The wealthy should use their millions to aid the public—“raise the moral and intellectual level of the masses”—and not hand out quarters to the poor. Carnegie claimed that the ideology of capitalism rested on natural and divine laws. “In the long run wealth only comes to the moral man”—material prosperity makes the nation “sweeter, more joyous, more unselfish, more Christ like.” Such arrogant capitalistic notions were resisted vigorously by the poor.

Capitalists often failed to understand their workers. Employers sought docile, sober workers who would do their jobs reliably without complaining. By 1880 five million Americans were engaged in manufacturing, construction, and transportation. They were paid employees, not producers and were dependent upon hourly wages and the good will of their employers. The worker was seen as “a mere machine”—he could not make the simplest decisions and had no self-respect. The degradation of the skilled labor class was one of the major grievances of labor. Wages were not enough to support a family—work was marred by inequities and corruption. Working families could survive only by “ruthless under consumption.” Workers were victims of business cycles—the winds of change swept many away. Piece work and lower wages were introduced to reduce labor costs. Whereas workers in earlier times had worked alongside their employers, now they were separated. Managers of large business rarely had personal contact with workers.

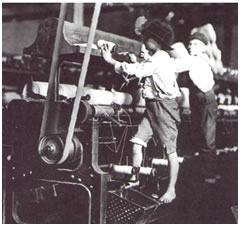

Women and Children in the Labor Force. Many new jobs for women were created during the Industrial Age. From 1880 to 1900 the number of employed women went from 2.6 to 8.6 million. In 1880 4% of clerical workers were women; by 1920 the figure was 50%, but women could not get management positions. Although middle class married women were able to stay at home, among the poor, women—and children—had to work. (Truant officers who patrolled factories to get children into school were thwarted by struggling parents who needed the extra income.) A state of quasi-slavery existed where parents bound children to work, but child labor would not be squarely addressed until the Progressive Era.

Women and Children in the Labor Force. Many new jobs for women were created during the Industrial Age. From 1880 to 1900 the number of employed women went from 2.6 to 8.6 million. In 1880 4% of clerical workers were women; by 1920 the figure was 50%, but women could not get management positions. Although middle class married women were able to stay at home, among the poor, women—and children—had to work. (Truant officers who patrolled factories to get children into school were thwarted by struggling parents who needed the extra income.) A state of quasi-slavery existed where parents bound children to work, but child labor would not be squarely addressed until the Progressive Era.

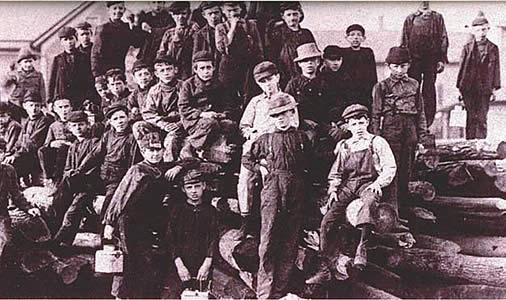

Unions were generally hostile to women; men believed women shouldn't work for wages because they undercut wage levels. Some separate women's unions did exist, and they sought special legislation for female workers, etc. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union led a massive strike against New York City sweatshops. Union leaders came from the middle class and were not militant, but insistent. In the 19th century no special concern existed over children or women doing hard work—they had always worked within the family on farms or in family businesses. By 1890 18% of the labor force consisted of children between the ages of ten and fifteen.

Labor Conditions. Industrial safety was a large issue: factory work was very dangerous, and it was difficult if not impossible to hold factory owners responsible for deaths and injuries. Around 1900 25-35,000 deaths and 1 million injuries per year occurred on industrial jobs. Many of the deaths occurred on railroad jobs, which were especially dangerous. Fires, machinery accidents, train wrecks and other misfortunes were common. No federal regulation of safety and no enforcement of state or local safety regulations existed. Insurance and pensions were rare, and courts were not sympathetic to worker claims; no liability was seen if the worker was negligent, or if the employer was not. The burden of proof was on the injured party to prove he or she had not been negligent—and it is difficult to prove a negative. Poor English was a problem; many workers could not read safety regulations or instructions on operating machines. Only about two percent of those injured or killed ever recovered on claims.

In all confrontations of the late 19th century, workers were generally losers. Immigrants and blacks were often targets of resentment because they were used as strikebreakers, or “scabs.” In general the union movement was secondary to the general struggle for jobs—in the labor game it was a buyers’ market. The age of industrialization was also the age of exploitation—of people, land, and resources—and while many benefited from the results, many also suffered. As industrialization and urbanization changed the face of America forever, those who took the time to look backward were astounded at how far the nation had come in just a few decades.

|

| Child Workers in America Lead to New Labor Laws |

Early Unions: The Knights of Labor. The Knights of Labor were organized in 1869 as a “Noble and Holy Order.” The Knights were a secret, Protestant society of Philadelphia tailors called together by Uriah Stephens. They were reformers who sought “equal pay for equal work.” By 1878 the Knights had become a national labor union. Their goal was to achieve a cooperative society by ending what they saw as the wage/slave system. They foresaw eventual cooperative ownership of mines and factories as well as consumer-producer cooperatives. They believed that every man should be “his own master” and that “an injury to one is an injury to all.” The Knights recruited members without regard for race, color, or sex. All workers were eligible for membership, including unskilled laborers as well as farmers and trade unionists. Their membership reached 700,000 by 1886. They called for an 8-hour day to spread out jobs and reduce fatigue that resulted in accidents. They advocated boycotts and arbitration instead of strikes, which they considered barbaric. They supported political reform, a graduated income tax and other measures. The special interests of craft unions eventually broke the Knights, and they were also damaged in the public eye by the activities of radicals and anarchists, as occurred in the Haymarket riot. (See below.)

The American Federation of Labor was a combination of national craft unions. It became known as the “aristocracy” of labor; it did not encourage unskilled workers. Samuel Gompers, former head of the Cigar Makers Union, founded the American Federation of Labor (AF of L) in 1886 and became its president, a position he held for almost 38 years. The AF of L raided the Knights of Labor for members and leaders as it sought more influence. The Federation’s goals were limited to what was achievable within the system that existed: shorter hours, better wages, and the right of collective bargaining. The AF of L did not threaten the capitalist system as the Knights had done. They sought no “pie in the sky” solutions, but rather worked for a smooth transition to a better existence for workers and their families. Always pragmatic, Gompers said the union movement was “of the working people, for the working people, by the working people.”

In February, 1912, Samuel Gompers wrote in McClure’s Magazine:

And what have our unions done? What do they aim to do? To improve the standard of life, to uproot ignorance and foster education, to instill character, manhood and independent spirit among our people; to bring about a recognition of the interdependence of man upon his fellow man. We aim to establish a normal work-day, to take the children from the factory and workshop and give them the opportunity of the school and the play-ground. In a word, our unions strive to lighten toil, educate their members, make their homes more cheerful, and in every way contribute an earnest effort toward making life the better worth living.

Specific goals of the American Federation of Labor included:

- “Job ownership”—the right to continue to work without being laid off arbitrarily.

- Immigration curbs to reduce the amount of cheap labor.

- Relief from technological unemployment.

- Labor legislation.

- Collaboration with employers.

Gompers was opposed to radicals and theorists; he sought practical solutions to issues of wages and working hours, not a socialist state. He pushed for labor legislation, but only as a secondary goal. He used the power of the strike carefully as a weapon to hurt profits and force stockholders to pressure management. He did not use strikes during bad times when scabs were available, but rather in good times, when it hurt owners more directly by cutting into profits.

Gompers was opposed to radicals and theorists; he sought practical solutions to issues of wages and working hours, not a socialist state. He pushed for labor legislation, but only as a secondary goal. He used the power of the strike carefully as a weapon to hurt profits and force stockholders to pressure management. He did not use strikes during bad times when scabs were available, but rather in good times, when it hurt owners more directly by cutting into profits.

Gompers was also opposed to creation of a Labor Party; he did not want labor making commitments to political parties. Dues were collected from members for strike funds, worker illnesses, etc., but not for political contributions. The AF of L had over 1 million members by 1901, and by 1917 it had 2.5 million members in 111 unions. Under Gompers’ leadership the AF of L grew to about 3 million members by 1924. Eventually the AF of L became involved with politics and backed friendly candidates.

Labor Militancy: Railroads, Haymarket, Homestead, Pullman

Events of the late 19th and early 20th centuries support Page Smith’s assessment of the differences between working men and business owners as the “war between capital and labor.” The revolutions that spread across Europe in 1848, often accompanied by violence, led to militancy among labor leaders who advocated revolutionary labor reforms. Workers emigrating to the United States after the Civil War, perhaps encouraged by the demise of American slavery, brought radical social ideas with them. When the headquarters of the first Communist International was moved to New York City in 1872, labor movements in the United States became more radicalized. Both the National Labor Reform Party (1872) and the Workingmen’s Party of the United States (1876) were Marxist or Marxist oriented.

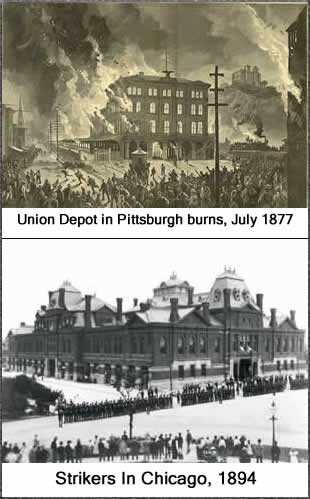

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877. An economic depression in Europe in 1873, combined with the turbulence of the post-Civil War years, led to a collapse of the American economy. Banks and businesses failed, unemployment rose to 14% and those who retained their jobs saw wages cut to as little as one dollar per day. The recession continued through the centennial year of 1876, and in July, 1877, a railroad strike broke out in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The Baltimore and Ohio railroad cut workers’ wages for the second time in months, and workers refused to let trains move. The governor sent state militia to address the crisis, but the soldiers refused to take action against the workers. The strike soon spread to Cumberland and Baltimore, Maryland. The president of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad refused to meet with or listen to strikers demands, and when the Maryland governor called out two regiments of the National Guard, street fighting broke out in the city of Baltimore.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877. An economic depression in Europe in 1873, combined with the turbulence of the post-Civil War years, led to a collapse of the American economy. Banks and businesses failed, unemployment rose to 14% and those who retained their jobs saw wages cut to as little as one dollar per day. The recession continued through the centennial year of 1876, and in July, 1877, a railroad strike broke out in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The Baltimore and Ohio railroad cut workers’ wages for the second time in months, and workers refused to let trains move. The governor sent state militia to address the crisis, but the soldiers refused to take action against the workers. The strike soon spread to Cumberland and Baltimore, Maryland. The president of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad refused to meet with or listen to strikers demands, and when the Maryland governor called out two regiments of the National Guard, street fighting broke out in the city of Baltimore.

The strike and then spread to Pittsburgh, where the worst violence occurred. On July 21 Pennsylvania militia engaged in gun battle with armed workers and were driven into a railroad roundhouse. Sixteen men were killed and 39 buildings were set on fire. As the strikers grew bolder, 20 more men were shot the next day. As the strike spread further across the country, other state militias as well as Pinkerton detectives were called out to break the strikes, and the railroads brought in scabs to replace striking workers. In the end over 100 men were killed and the damage to railroad property totaled $100 million. People everywhere feared a revolution, and marches and demonstrations in New York, Chicago, St. Louis, and other cities included both men and women. Labor leaders claimed that the great strike showed that capital would justify the use of any means whatsoever to break the power of the Unions.

Haymarket. In May 1886 during a communist-led workers’ meeting in Haymarket Square aimed at the McCormack plant in Chicago, a bomb exploded. It targeted police who had been called in to break up the meeting. Seven policemen were killed and dozens wounded. In the resulting trial a number of radical leaders were convicted and were sentenced to long prison terms; seven of those convicted were sentenced to death. Four convicted men were eventually executed; the others had their sentences commuted. Because of concerns over labor violence, public opinion tended to side against the workers who had precipitated the violence in the first place. The overall impact of the Haymarket massacre was that the union movement was hurt. The riots fed into the common belief that radicals had led American workers astray and that labor unions were a threat to law and order.

Homestead. When a strike broke out at the Carnegie Steel Company plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, company manager Henry Clay Frick sent for Pinkerton detectives to deal with the strike. Workers then fired on two barges being towed up the Monongahela River with the detectives on board, killing seven. The strike was eventually broken when state militia took over. In the aftermath of the violence a Russian anarchist, Alexander Berkman, attacked and stabbed Henry Clay Frick, which resulted in his being sentenced to 21 years in prison. The Amalgamated Association of Iron & Steel Workers was crushed, and another steel workers union did not arise for decades.

Pullman. Yet another breakout of labor militancy occurred at the Pullman Palace Car Company in Pullman, Chicago. George Pullman organized the Pullman sleeping car company in 1867 and created a company town. Pullman’s paternalism meant that the company controlled everything in the worker’s lives—banks, churches, schools, utilities, and so on. As one worker resident put it, “We are born in a Pullman house, fed from the Pullman shops, taught in the Pullman school, catechized in the Pullman Church, and when we die we shall go to the Pullman Hell”

In 1893 Pullman cut workers’ wages by 25-40% without lowering rents or other living costs in the town. He fired negotiators who tried to work through the situation. The American Railway Union under Eugene Debs called a strike, asking workers not to service trains pulling Pullman cars. Railway managers could have sidelined the Pullman cars until dispute was settled, but they saw an opportunity to break the union. The federal government got involved when United States Attorney General Olney obtained an injunction against the union so as not to “hold up the mails.” President Cleveland sent federal troops to Chicago to run the railroads, and the strike ended several days later. Criminal charges were brought against the strike organizers, and Eugene Debs was jailed for conspiracy. The Pullman strike expanded the courts’ propensity to intervene in labor disputes.

Progressive Relief. Once the Progressive movement got underway after the turn of the century, things slowly began to improve. In 1903 the Department of Commerce and Labor was established. It included a Bureau of Corporations to help corporations clean up their acts and avoid antitrust suits. In 1904 a National Child Labor Committee was formed to deal with the oppressive conditions under which children were forced to work. Without schooling they would be bound to a lifetime of dead-end jobs and drudgery.

Progressive Relief. Once the Progressive movement got underway after the turn of the century, things slowly began to improve. In 1903 the Department of Commerce and Labor was established. It included a Bureau of Corporations to help corporations clean up their acts and avoid antitrust suits. In 1904 a National Child Labor Committee was formed to deal with the oppressive conditions under which children were forced to work. Without schooling they would be bound to a lifetime of dead-end jobs and drudgery.

The year 1905 saw the appearance of the Industrial Workers of the World, the I.W.W.—a radical Union. Their aims were to achieve worker solidarity, promote strikes and carry out sabotage where peaceful methods failed. Known as the “Wobblies,” they proclaimed that “the final arm of labor is revolution.” They believed workers should seize and operate industrial machinery and transfer ownership of the companies to workers. Many leaders were communist oriented if not outright party members. An I.W.W. leader, William D. "Big Bill" Haywood has been described as “one of the foremost and perhaps most feared of America's labor radicals.” He was a large man with a resonating voice and had little respect for the law. Haywood organized union activists, intimidated industrial managers and often found himself in trouble with legal authorities.

Labor discontent continued well into the 20th century. During the Lawrence Strike of 1912, hundreds of women from many ethnic backgrounds braved police officers as they picketed a plant where they made coats. With the wages they earned, they could not even afford to buy the coats that they themselves produced. During the early 1920s, the West Virginia Coal Field wars saw violence in the street. In the 1930s the Teamsters Union led by Jimmy Hoffa was often involved in violent confrontations. The United Mine Workers under John L. Lewis struck in 1943 during the height of World War II, which created anger among the American people and led President Roosevelt to take over the mines.

Although industrial unions still have large memberships, most of the largest unions today are the service unions—hotel and restaurant workers, teachers, government employees. Although strikes are rare and violence even less frequent, worker organizations still provide a strong voice in support of laws that protect workers.

Chronology of the Union Movement |

|

| 1820-1850 | Artisan groups form associations based on the idea of guilds hearken back to medieval times. The aim is to protect the integrity of various skilled trades such as blacksmithing, watch-making, and so on. |

1850-1860 |

This decade sees the rise of national trade unions who stress general business objectives. Members are typographers, cigar makers, stone cutters, etc. In the 1850s the cost of living rises 12%, but wages rise only 4%. Many strikes in occur 1860. During the Civil War there are few strikes, but real wages fall, partly due to inflation caused by wartime spending. |

1864 |

The American Emigrant Company is formed by businesses to import laborers. Imported labor contracts are later declared illegal. |

| 1869 | The Knights of Labor are formed. |

1864-1873 |

The National Trade Union Movement is an attempt to organize different labor groups and leads to 3-400,000 members in various unions. Employers also organize to guard against what they see as labor monopolies. The movement is rooted labor discontent and Middle Class fear of radicalism and seeks cooperation between capital and labor. Resistance to threats of (foreign) anarchists leads to stronger police forces and associations of businessmen. |

1866 |

A National Labor Union meeting in Baltimore calls for 8-hour day. State labor laws are varied, weak, and often ignored. They have 640,000 members by 1868. |

| 1872 | In 1872 the NLU becomes the National Labor Reform Party, whose policies are militant and pro-Marxist. The Party dies quickly. |

1874 |

The Molly Maguires, a secret miners' organization, grows out of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, an Irish group. Their violent tactics lead to the conviction of 24 members, of whom 10 are hanged. |

1877 |

Watershed year—the year of the Great Railroad Strike. Violence spreads across the country. |

1880-1900 |

Strikes become more frequent, larger. |

1882 |

The First Labor Day is celebrated in New York City. The federal Labor Day is holiday is proclaimed in 1894 by Congress, to be held on the 1st Monday in September. Meanwhile European labor movements are begin to spread to the U.S., with many radicals among them, including Marxian Socialists, anarchists and communists. |

1886 |

The American Federation of Labor is founded by Samuel Gompers. |

| 1886 | The Haymarket Riots break out in Chicago. |

| 1892 | The Homestead Massacre in Pennsylvania occurs at Carnegie Steel.. |

1892 |

Federal troops are dispatched to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, to put down miner's strike. Other strikes also occur in that year. |

| 1894 | The Pullman Strike in Pullman, Illinois breaks out. |

1902-1922 |

The United Mines Workers Union leads strikes from Pennsylvania to Colorado. The “West Virginia Coal Field Wars” happen during the 1920s. (See the John Sayles film Matewan) |

Immigration and Urbanization: The Growth of the Cities

Urbanization is the process of population concentrating in cities. As technology—machinery, irrigation, fertilization—made farming more efficient it became increasingly difficult for farmers to make a living. The new technology required less labor and increased farm output, but the increased supply drove down farm prices. At the same time, in the last half of the 19th-century industrialization saw a huge growth in factories. Their workers produced tools, appliances, household goods, machines, and many other commodities that a growing middle class were prepared to buy. Factories tended to congregate in urban areas, near transportation facilities and financial centers, where ready labor was available. Thus a push-pull phenomenon led to ever larger city populations, as people left farms to seek employment in urban areas. Further, ethnic enclaves were constantly fed by the influx of immigrants seeking people of common background with their own.

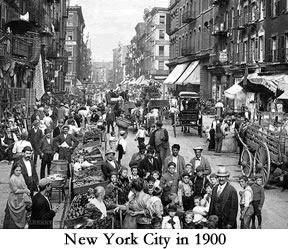

American cities in the last half of the last century could be seen in a sense as all things to all people. Certainly the growing population centers were vibrant hubs of activity where, with a little luck, a few skills and plenty of energy, people could prosper economically. Farmers and residents of rural areas, however, saw them as pits of degradation and corruption. All the same, many young people, faced with a lifetime of hard, often unrewarding work, left their family farms in search of other opportunities. Immigrants saw America’s cities as perhaps crowded and dirty but filled with chances for work, education and cultural stimulation. The working poor saw them as prisons, perhaps, or merely places where they could eke out an existence, living from day to day. Many middle class people increasingly found them places from which to escape to the suburbs, just as long as they were able to commute to “downtown” for work via train, trolley or, eventually, automobile.

Despite crowded conditions, cities were marked by splendid museums, theaters, skyscrapers, parks and mansions, but they just as frequently had appalling slums, crime, prostitution, and disease. In those pre-air conditioning times, cities also had horribly malodorous air from poor plumbing, inadequate waste removal and the droppings of thousands of horses. Cities were simply unable to keep up with the influx of immigrants and refugees from the farms. They lacked the wealth and resources to handle the multiplying problems, and their political systems were often tainted by corruption. Yet they were vibrant, lively places, and despite the odds, people were able to survive and even prosper.

When contagious diseases invaded the cities, the fevers spread rapidly. Medical practice was not yet advanced enough to cope with large numbers of sick people. The challenge of providing clean water and some kind of sewage facilities also stretched urban planners and managers to and beyond their limits. The result was that around the turn of the century in 1900, the slums in American cities were among the worst in the history of the world. Families with five or more children were crammed into tiny two-room spaces, often with only a blanket over a cord providing any degree of privacy for the adults. In the absence of adequate heating and air-conditioning, cramped quarters became insufferable in the summer, when insects and vermin thrived. During the winter people huddled under blankets to keep warm as heating was often erratic. Plumbing was often primitive, and the resultant contamination of living areas exacerbated already difficult conditions. Churches, once the refuge of the poor, simply became incapable of meeting the demand, especially as wealthier congregants fled to greener pastures.

When contagious diseases invaded the cities, the fevers spread rapidly. Medical practice was not yet advanced enough to cope with large numbers of sick people. The challenge of providing clean water and some kind of sewage facilities also stretched urban planners and managers to and beyond their limits. The result was that around the turn of the century in 1900, the slums in American cities were among the worst in the history of the world. Families with five or more children were crammed into tiny two-room spaces, often with only a blanket over a cord providing any degree of privacy for the adults. In the absence of adequate heating and air-conditioning, cramped quarters became insufferable in the summer, when insects and vermin thrived. During the winter people huddled under blankets to keep warm as heating was often erratic. Plumbing was often primitive, and the resultant contamination of living areas exacerbated already difficult conditions. Churches, once the refuge of the poor, simply became incapable of meeting the demand, especially as wealthier congregants fled to greener pastures.

In places like New York, more foreign tongues were spoken than English, and many ethnics did not “melt.” In general they got along, and for many, even the worst conditions were far less hopeless than those they had left behind. Between 1870 and 1900, the city became a symbol of a new America to which people flocked, drawn by economic opportunity and the promise of a more exciting life. Cities grew upward and outward on the basis of technological progress. The use of steel beams allowed architects to raise buildings to previously impossible heights, and the streetcar allowed those with sufficient wealth to move from the crowded city centers to the greener suburbs, which produced an increasingly stratified and fragmented society. Skyscrapers and suburbs became the defining characteristics of the American city.

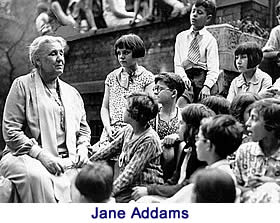

Settlement Houses. Coping with the problems of the cities, especially in poorer areas, was beyond the ability of city governments and of churches. Into the vacuum stepped a new breed of professional social workers, often women, who created what were called settlement houses to alleviate the appalling conditions that existed in the industrialized cities. They offered practical education and English language training. They also dealt with city hall and did their best to cut red tape. In the political arena they worked for reforms in areas such as such as public health and child labor. The settlement house women were spiritual cousins of female reformers working to gain women’s suffrage and reduce prostitution and drunkenness. The most famous of these workers was Jane Addams, whose Hull House in Chicago offered both classical academic and practical education to anyone who lived in the slums.

For college educated women around the turn of the century there were few opportunities to put their education experience to practical use. Business management was virtually closed to them, as were professions such law, medicine, the military, the ministry, and higher education, with few exceptions. In general women were confined to clerical work below the executive level, grueling factory labor, domestic employment, missionary work, nursing, and primary and secondary education. The settlement house movement was, therefore, to some extent a product of women's frustration. Social work as it evolved in the 20th century was not yet a full-blown profession; educated women who saw the terrible needs of poor, often immigrant, women in the cities, developed the profession on their own. Female social workers frequently got financial assistance and moral support from fathers, husbands or businessmen who shared their views.

For college educated women around the turn of the century there were few opportunities to put their education experience to practical use. Business management was virtually closed to them, as were professions such law, medicine, the military, the ministry, and higher education, with few exceptions. In general women were confined to clerical work below the executive level, grueling factory labor, domestic employment, missionary work, nursing, and primary and secondary education. The settlement house movement was, therefore, to some extent a product of women's frustration. Social work as it evolved in the 20th century was not yet a full-blown profession; educated women who saw the terrible needs of poor, often immigrant, women in the cities, developed the profession on their own. Female social workers frequently got financial assistance and moral support from fathers, husbands or businessmen who shared their views.

Perhaps the most famous woman who ever worked in the settlement house movement was Eleanor Roosevelt. Early during her marriage to Franklin Roosevelt she worked with settlement houses in New York City. On one occasion she had to escort a young woman back to her residence in one of the city's worst slums. Being somewhat uncertain about what she might find there, she asked Franklin to accompany her, and he did. (He was not yet involved in politics but was a practicing attorney in New York City.) When they had delivered the woman to her squalid quarters, he said to Eleanor as they emerged, “My God, I didn't know people lived like that.” FDR's biographers mark this as a consciousness-raising event in his political evolution; the remark also demonstrates how oblivious many prosperous people were to the horrifying conditions in which millions of people lived.

Immigration

The United States is a nation of immigrants, perhaps more so than any other major nation on the planet. Even our Native American ancestors migrated from Asia tens of thousands of years ago and are actually native to North Asia. Between the end of the Civil war and 1910, 25 million people entered the U.S. They joined rural Americans in the cities looking for jobs and other  opportunities. Compared with those who had immigrated to America before the Civil war, these “new” immigrants came from different parts of Europe: Italy, Greece, Poland, Hungary, Russia, Turkey, Lithuania, Romania. They practiced different religions, including different forms of Christianity, and brought new and strange cultural ideas with them. The new immigrants also frequently ghettoized themselves, settling in ethnically solid neighborhoods that persist to the present day. (Chicago’s Polonia is home to over one million residents of Polish descent. Chicago is considered the largest Polish city besides Warsaw, and in Polonia, where Polish businesses, restaurants, newspapers and churches thrive, Polish is the predominant spoken language.)

opportunities. Compared with those who had immigrated to America before the Civil war, these “new” immigrants came from different parts of Europe: Italy, Greece, Poland, Hungary, Russia, Turkey, Lithuania, Romania. They practiced different religions, including different forms of Christianity, and brought new and strange cultural ideas with them. The new immigrants also frequently ghettoized themselves, settling in ethnically solid neighborhoods that persist to the present day. (Chicago’s Polonia is home to over one million residents of Polish descent. Chicago is considered the largest Polish city besides Warsaw, and in Polonia, where Polish businesses, restaurants, newspapers and churches thrive, Polish is the predominant spoken language.)

The wave of immigrants started schools and churches and generally adapted themselves to American culture while retaining their own individuality, both enriching and being enriched by the interaction. They found much to admire in American democracy and took enthusiastically to politics and education, areas from which they had generally been excluded in their native lands. Immigrants who passed through Ellis Island, some of whom are still alive, often recall with wonder the feelings they had upon entering New York Harbor and seeing the statue with those words inscribed. One man said, “My God, I thought the ship was going to tip over! Everybody rushed to the side to stare at the Statue of Liberty!” (The Ellis Island Museum and web sites have recorded testimonies of immigrants who passed through its gates.)

Even from the beginning, the new arrivals were not welcome in all quarters. In colonial times there was squabbling among early English settlers—Puritans, Anglicans, Quakers, Catholics—as people exhibited the very human tendency to want to be among others who looked and thought and acted just as they themselves did. An early colonist in New Jersey spoke with wonder of what was for him a troubling diversity he experienced at a wedding, where the bride's mother and father were of different backgrounds, perhaps German and Scottish, and the groom's parents were a French Huguenot and a Swede.

The first group who found themselves most unwelcome were Irish Catholics. They began to come to the United States in large numbers in the early 19th century as economic conditions, the most terrible of which was the potato famine, plagued the Irish people. They came in what were often called “coffin ships” because of the numbers who died on board. Interestingly, about a third of those immigrants did not speak English but Irish, a Gaelic language that has rarely traveled far outside of Ireland itself. Further, the Irish are ethnically different from the other groups in the British Isles, and those differences were often exaggerated by people who were unkindly disposed toward the Irish. As immigrants from Ireland began to fill up some of the poorer districts of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, they found their children abused, their churches attacked, and they were greeted with signs such as “Dogs and Irish keep out!” The election of John F. Kennedy, an Irish Catholic, to the presidency of the United States in 1960 was a culminating milestone in the acceptance of Irish people among Americans.

America has always needed cheap labor, which provided much of the impetus for immigration, as it still does. The new immigrants filled up the cities faster than they could be accommodated, and the result of all this was an explosion in the size of American cities. The population of the United States rose from 31 to 92 million between 1860 and 1910. In the same period, the population of New York City rose from 800,000 to nearly 5 million.

The newcomers found themselves jammed into tenements, crowded apartments and shoddy houses with few sanitary facilities. The worst slums in the world were supposed to have existed in Chicago, a situation exacerbated by the stockyards that supplied the meat-packing industry. Yet immigrants continued to come in pursuit of what has been called the American dream. Meanwhile the cities grew both outward and upward. Tenement houses holding hundreds of families sprang up in the poorer sections of cities, and sanitary facilities, utilities, and other sources of domestic comfort were unable to keep up with the demand. Oppressive labor conditions and unsteady employment also caused crime to flourish, and police forces were not yet equipped to keep up with the spreading problem. Disagreements among ethnic minorities led to gang warfare, primarily among Irish, Italian and Jewish communities in New York and Chicago. In 1880 in New York City a majority of the population did not speak English at all.

The immigrants who arrived in the latter decades before 1910 changed the ethnic character of the United States even more profoundly than had the English, Irish and Germans, coming as they did from Southern and Eastern Europe. There are still parts of the United States where one can hear Swedish, Italian, Polish, Yiddish, Spanish and many other languages spoken in the streets.

The New Colossus |

|

For much of our history most Americans have been proud of our openness to peoples from other lands. Consider the words of Emma Lazarus's famous poem, “The New Colossus”: Emma Lazarus' precocity as a poet brought her works public attention when she was a girl of eighteen, but her interest in her Jewish heritage was slower to develop, and lay dormant until she learned of the 1879-1881 Russian pogroms against the Jews. When Jewish refugees began arriving in the United States in 1881, Miss Lazarus organized relief programs and published a bitter attack on the pogroms in Century Magazine. The last five lines of her sonnet, "The New Colossus," were selected for inscription on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, dedicated October 28, 1886.Source Poems, Boston, 1989, Vol. II. |

|

THE NEW COLOSSUS |

|

Since much of the wealth in the nation was consolidated in the hands of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, the social tensions that resulted from immigration and the great disparity in wealth between social groups was multiplied. In the 1920s the doors began to close for a time, and severe restrictions were placed upon immigration. A quota system was established whereby those who were admitted to the United States were most likely to gain entry if they were of the ethnic groups already well-established here. When an annual quota of 150,000 for immigration was established (as opposed to years when almost a million had entered) approximately 60% of immigrants had to come from Germany and the British Isles. The rest of the world had to divide up the 40% left over. As World War II approached and international troubles multiplied, immigration slowed once more. It began again after the war when millions of displaced persons, wartime refugees far from their homes, sought new beginnings here and elsewhere.

As the prospering middle class sought to escape the rigors of inner-city life, suburbs began to blossom. Suburban development was aided by streetcars, buses and other mass transportation systems that began to flourish with refinements in the supporting technology. But in cities such as Chicago, with the pall of odors that emanated from the infamous stock yards, life remained barely tolerable. As mentioned above, thousands of people in New York and other cities did not speak English, and in hundreds of communities across the country church services were conducted in Greek, Polish, Italian, and other languages.

Immigrants by the hundreds of thousands continued to flood the country. Somehow the nation was able to absorb them. It was not until the Progressive Era, an age of what has been called “urban socialism,” that conditions began to improve. Progressive politicians, business leaders, social workers and others, spurred on by the growth of journalism, tackled the massive problems hanging over the cities of America.

In recent years the tide of immigration has continued and has been expanded by large numbers of illegal immigrants. Most of them enter by crossing the Mexican-American border, though others have been smuggled in on ships, through Canada and via various other devious routes. The United States is still wrestling with the issue of immigration, especially in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

The fact remains that there are few places in the world that accept large numbers of immigrants. The United States, Canada and Australia are the most open and probably account for the great bulk of international migration. How the United States will continue to deal with immigration issues remains to be seen. Our political leaders recognize the challenges, but no clear-cut solution is in sight. Attitudes are far ranging, starting from those of people such as former Mayor Rudy Giuliani of New York City, grandson of Italian immigrants. His openness and praise of our immigrant population is rare in some political circles. On the other end of the spectrum are descendants of a group once known as “Nativists,” people who felt that only those who were born in this country have a legitimate claim to all its opportunities. Opinions range widely in between, and only a full understanding of the history of our immigrant population can lead us to satisfactory solutions.

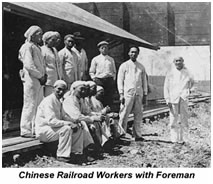

During the last decades of the 19th century the building of the transcontinental railroads demanded huge numbers of laborers, and it was Irish and Italians and Chinese who did much of that work. When that great building boom subsided, the immigrants remained. The Central Pacific Railroad, which built the western portion of the first line from Sacramento, California, to Promontory, Utah, through the Sierra Mountains, used primarily Chinese laborers. Since most of the Chinese who came to the country to work were males, and few came with families, when the railroads were finished, they found themselves living in ghettos in the western cities with little female companionship. The social problems which arose from that were predictable, and the American response was to pass laws to restrict and discriminate against those of Asian ethnicity.

Emigration from China to the United States was driven by many of the same motives that brought Europeans to this country. The Chinese, however, faced problems that were far more pronounced than those that affected Europeans, even those from Southern and Eastern. Chinese immigrants were subject to an obvious racist bias directed towards all peoples of Oriental background. They were attracted to this nation primarily for economic reasons. Having heard of the California gold rush, they hoped to be able to accumulate wealth and return to China. Few Chinese immigrants became rich from gold, but they soon discovered that their labor was a source of steady income if not instant riches. Centered in California, the Chinese immigrant population constituted approximately one quarter of the California workforce by the year 1880.

Emigration from China to the United States was driven by many of the same motives that brought Europeans to this country. The Chinese, however, faced problems that were far more pronounced than those that affected Europeans, even those from Southern and Eastern. Chinese immigrants were subject to an obvious racist bias directed towards all peoples of Oriental background. They were attracted to this nation primarily for economic reasons. Having heard of the California gold rush, they hoped to be able to accumulate wealth and return to China. Few Chinese immigrants became rich from gold, but they soon discovered that their labor was a source of steady income if not instant riches. Centered in California, the Chinese immigrant population constituted approximately one quarter of the California workforce by the year 1880.

The most notable contribution of the Chinese immigrants was their work on the first transcontinental railroad. The Central Pacific hired approximately 15,000 Chinese laborers to work on the line. During the tunneling through the Sierras, the Chinese became adept in the use of hammers, chisels and black powder as they burrowed through the granite at the agonizingly slow rate of about eight inches per day. During the winter months Chinese workers dug tunnels through the snow from their cabins to the tunnel work sites and might go for weeks without ever seeing sunshine. Yet they labored diligently and contributed significantly to the progress of the great iron railway across America.

Since the great majority of the Chinese immigrants were young single males, once the railroad work was finished, they had difficulty assimilating into American society. They settled into all-male communities in cities such as San Francisco and created businesses operating restaurants and laundries. Without a family-oriented environment, however, those conditions fostered prostitution, gambling and other socially undesirable practices. The depression years of the 1870s contributed to the anti-Chinese feelings, with the result that Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The act effectively ended Chinese immigration, as only those with family members already in the United States were allowed to enter the country. The preamble to the Act stated: “ [I]n the opinion of the Government of the United States the coming of Chinese laborers to this country endangers the good order of certain localities within the territory thereof.”

The story of the Chinese in America has been told beautifully by a skilled young historian, Iris Chang, author of a best-selling book, The Rape of Nanking, about the Japanese occupation of that city during World War II. Her most recent work, The Chinese in America, covers 150 years of Chinese immigration to the United States, including anecdotes of Chinese immigrants and their families as they adapted themselves to the changing American culture. She traces the story of the Chinese from the building of the transcontinental railroads to modern times, highlighting the many accomplishments of the Chinese in such areas as science and technology. Iris Chang is a second-generation American, born in Princeton, New Jersey, with a graduate degree in writing from the Johns Hopkins University. Her fascinating book should be read by anyone interested in the Chinese experience in America. (Tragically, Irish Chang died by her own hand in November, 2004. It has been speculated that her work on The Rape of Nanking, the story of the brutal treatment of Chinese women by Japanese soldiers during World War II, may have contributed to her death. She was 36 years old.)

| Sage History Home | Gilded Age Home | Updated February 5, 2018 |