Expansion and War: The United States 1840-1860

Copyright © Henry J. Sage

2010

|

| George A. Crofutt, artist. "American Progress," or "Manifest Destiny," ca. 1873. |

Introduction and Overview

This part of American history, known as the ante-bellum (before war) era, begins with expansion and the great migration across the continent west of the Mississippi. The idea of manifest destiny—that the United States was destined to occupy the entire North American Hemisphere—came of age in the 1840s. It began with the annexation of Texas, which led to the Mexican-American War and the resulting great land cession. It was also the time of “Oregon Fever” as wagon trains took pioneers over the Rocky Mountains to the Willamette and Columbia River valleys.

The addition of these new territories, which eventually became new states, reopened the debate over the expansion of slavery. Until this time the issue had been more or less settled by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. That debate dominated the decade of the 1850s as the nation drifted inexorably toward separation and the Civil War, sometimes called the “War Between the States,” or the “Second American Revolution.”

Those years were also marked by significant social changes resulting from a number of factors. The discovery of gold in California spurred a huge migration across the continent (or around Cape Horn) as well as immigration from Central and South America and Asia. A new wave of immigration from Europe centered on immigrants from Ireland who sought opportunities unavailable at home, and spurred in the 1840s by the potato famine that devastated the Irish homeland.

At the same time, a new religious revival was “burning over” much of Middle America. The Second Great Awakening and the rise of new religions—such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, or Mormon Church—characterized the period. Religious motives helped drive many reforms forward; a women's movement was beginning, temperance lecturers railed against the evils of strong drink, and prison and insane asylum reforms were in the making. In keeping with Jeffersonian ideals, a number of states adopted public education as a mandate; hundreds of thousands of American children received a free basic education in primary schools. Secondary schools and private academies led students into new colleges and universities that offered advanced education to more young people, including women in some of the more progressive institutions. The Romantic Era in literature seemed to fit the mood of America. The first group of great American writers told the American story in poetry, fiction and essays. America was finding its voice.

In keeping with the spirit of reform, the abolition movement gained traction during the 1840s, spurred by both internal and external events. The British Empire had finally shut down slavery in all its possessions, and many religious groups saw slavery as unchristian, though not in the American South. Thus after a period of relative calm following the Missouri Compromise, more and more Americans noted with considerable discomfort that the slavery issue was still present and becoming ever more heated. Exercising their constitutional right to petition the government, northerners began submitting anti-slavery petitions to Congress. Pro-slavery members introduced “gag orders” that automatically tabled such resolutions so that they would not have to be discussed. Personal liberty laws passed in Northern states challenged federal authority to recapture fugitive slaves, abolitionists thundered that slavery was a sin, and Southern plantation owners began calling slavery a “positive good,” a notion probably unthinkable before 1800 but deemed necessary to counter abolitionist charges. By 1850 talk of secession and war was common both inside and outside Congress, and every election from 1844 through 1860 had the “peculiar institution” as a backdrop. It was only a matter of time until something blew up.

Tension continued to rise throughout the decade of the 1850s, starting with passage of the 1850 Compromise laws. They were followed by the publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin, which in turn was followed by violent protests in Northern cities as slave trackers attempted to capture runaways and take them back to the South. Passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 led to violence in the Kansas Territory, and the Dred Scott decision both clarified and exacerbated the slavery issue. Lincoln's famous debates with Senator Stephen Douglas during the 1858 Senate race in Illinois, John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry and subsequent trial and death by hanging kept the issue burning. Finally, the divisive election of 1860 led to the secession of South Carolina. Ten additional states eventually joined South Carolina to form the Confederate States of America.

The second generation of American leadership was dying. By 1852 Calhoun, Clay and Webster were all gone. The party system took firmer hold as the two major parties—the Democrats and Whigs—vied for the presidency and 1840, 1848 and 1852. The Whig Party broke up following the election of 1852, partly because of disagreements of slavery, but then another party arose: The Republican Party was founded in Ripon, Wisconsin, in 1854. Democrat Stephen Arnold Douglas of Illinois became the most powerful public figure of the early 1850s, and Jefferson Davis gradually assumed the mantle of John Calhoun as spokesman for the South. Although Abraham Lincoln had served in Congress from 1847 to 1849, he was all but unknown outside Illinois, even while unsuccessfully pursuing higher office. He arrived as a national figure in 1858 on the strength of his debates with Douglas, although he lost that race. His eloquent speeches during those debates, widely published, brought him to the presidency in 1861.

The Civil War is the central event of the American past. In a real sense it divides American history into two major segments: before and after that great conflict, which was also the deadliest war in American history. It is generally understood that the Civil War brought the end of slavery, but it did much more. The war between the states changed the relationship between the federal government and the states forever. It provided a backdrop for the beginning of the civil rights movement for African-Americans, a movement which is still being played out. (The election of Barack Obama in 2008 is the most significant recent milestone in that movement.)

Early American history has a plot; it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. The beginning was the period of colonization and colonial development when Europeans flocked to America’s shores and built a new society. The middle section of the story was the era of the American Revolution, the creation of a new and democratic republic unlike anything the world had seen before. But in the latter decades of that long middle period of American growth, the beginning of the end of the early part of American history began to loom, as secession and the possibility of war welled up across the American landscape. By the end of this period of American history the nation stretched from coast to coast. The states of California and Oregon had joined the Union, and the territory which eventually became the “lower 48”—the area between Mexico and Canada—was intact. Although much of the western territory remained sparsely populated, the outlines of the trans-continental nation had been formed. The Civil War was the last act in the first part of American history.

The John Tyler Administration: A President Without a Party

John Tyler was the first vice president to succeed to the office of president on the death of his predecessor. William Henry Harrison's inaugural address was the longest in history. The weather conditions were bad on the day of his address, cold and rainy with sleet. As a result, Harrison contracted pneumonia and died one month later. The Constitution was somewhat ambiguous on the subject of succession in such cases until the 25th Amendment was passed. Article II, Section 1 stated: “In case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case or Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability ... ”

The precedent Tyler set—he moved into the White House and assumed the title and role of president—carried through until the 1960s. The United States has had the good fortune not to have the office of president vacated when there was no vice president, though there were numerous opportunities for that to happen.

John Quincy Adams was not pleased with the transition; he wrote in his diary:

At thirty minutes past midnight, this morning of Palm Sunday, the 4th of April, 1841, died William Henry Harrison, precisely one calendar month president of the United States after his inauguration. …

The influence of this event upon the condition and history of the country can scarcely be seen. It makes the Vice-President of the United States, John Tyler of Virginia, Acting President of the Union for four years less one month. Tyler is a political sectarian, of the slave-driving, Virginian, Jeffersonian school, principled against all improvement, with all the interests and passions and vices of slavery rooted in his moral and political constitution—with talents not above mediocrity, and a spirit incapable of expansion to the dimensions of the station upon which he has been cast by the hand of Providence, unseen through the apparent agency of chance. To that benign and healing hand of Providence I trust, in humble hope of the good which it always brings forth out of evil. In upwards of half a century, this is the first instance of a Vice-President's being called to act as President of the United States. ...

Others in Congress besides John Quincy Adams were likewise unhappy with Tyler’s bold, preemptive act in simply taking over the office of president. In the long run it was probably better, however, that Tyler behaved as he did; otherwise, the selection of a vice president could have become messy indeed.

(Six more presidents died in office after Harrison before the 25th Amendment went into effect: Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, Harding, Roosevelt and Kennedy. In each case the vice president took over without any sort of rancor beyond the shock of the incumbent’s death.)

In any case Tyler was probably better qualified than Harrison, having been governor of Virginia, chancellor of the College of William and Mary and a United States Senator. But Tyler was an “Old Republican.” As a “nominal” Whig only, he had broken with President Jackson over the issue of nullification. As a states’ righter, Tyler was bound to disagree with Henry Clay, leader of the Whig Party. Clay was miffed at having been denied the nomination for president and was in no mood to bow to the wishes of the new president.

In any case Tyler was probably better qualified than Harrison, having been governor of Virginia, chancellor of the College of William and Mary and a United States Senator. But Tyler was an “Old Republican.” As a “nominal” Whig only, he had broken with President Jackson over the issue of nullification. As a states’ righter, Tyler was bound to disagree with Henry Clay, leader of the Whig Party. Clay was miffed at having been denied the nomination for president and was in no mood to bow to the wishes of the new president.

Clay, who was now in the Senate, reintroduced his “American System” program shortly after Tyler took over. It called for repeal of the independent treasury, recreation of the Bank of the United States, distribution of profits from land sales and raising tariffs, which he hoped the West would back in return for roads, canals and other “internal improvements.” He also favored allowing squatters to occupy and buy public land under a “Preemption Act.”

Tyler signed several of Clay's bills, but he vetoed Clay’s bank bill, and the Senate failed to override the veto. When Tyler vetoed a second bank bill, all his cabinet members resigned except for Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who was occupied with foreign problems. Tyler called bills containing amendments on other issues “wholly incongruous” and had no hesitation to use the presidential veto on other than constitutional grounds.

Anticipating a fight with Clay’s Whigs, Tyler quickly appointed new cabinet members, and Clay tried to hold up Senate approval, but Tyler threatened to suspend government services until the Senate acted. In the end, all his appointments were approved. Whigs also introduced an impeachment resolution over the issue of Tyler’s “legislation usurpation” based on the belief, despite Jackson’s legacy, that the president may veto bills only on constitutional grounds. The argument was rooted in Article I, Section 1 of the Constitution: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” The impeachment resolution failed in the House of Representatives by a vote of 127-84, meaning that if only 22 votes had gone the other way, Tyler would have been impeached. He would probably not have been convicted by the Senate, however, since that requires a two-thirds majority.

In the 1842 congressional elections, the Whigs lost power to the Democrats, and Tyler felt vindicated in his resistance to the Whig program. He was, however, a president without a party and had no chance of being reelected in 1844. Henry Clay resigned from the Senate to prepare for the presidential campaign of 1844, when he became the nominee of the Whig party.

Dorr’s Rebellion. The movement for more democratic government led to serious problems in the state of Rhode Island in 1842. From colonial times, only property owners had been eligible to vote in Rhode Island, and by 1840, that meant that less than half of the adult male population could vote. A committee of disfranchised voters held a meeting and passed a “People's Constitution” providing for full white manhood suffrage in December 1841. The state legislature then called a convention to revise the state constitution but failed to extend the franchise, siding with the landowners, who were opposed to extending the vote to non-landowners. The two separate groups held their own elections in the spring of 1842, which for a short time resulted in two governments within the state.

Supporters of extending the franchise elected Thomas W. Dorr as governor and controlled the northern part of the state. Samuel W. King was inaugurated at Newport in the Southern part of the state and declared the Dorr party to be in a state of insurrection. Both sides appealed to President Tyler for assistance, but he announced that he would intervene only if necessary to enforce Article IV, Section 4, of the Constitution, which requires the United States to guarantee every state a republican form of government. Dorr’s followers failed in an attempt to take the Rhode Island State Arsenal. After fleeing the state, Dorr later returned, was tried and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was granted amnesty in 1845. In 1843 the state adopted a new constitution with more liberal voting requirements: Any adult male of any race could vote upon payment of a one dollar poll tax.

American Foreign Relations in the Tyler Years

The discussion in this section is based on Thomas A. Bailey, A Diplomatic History of the American People, 10th ed., New York: Appleton, 1969, 204-240.

America has always had the luxury of not having to worry overmuch about defending its borders. The oceans provide a virtually impenetrable barrier against hostile landings, and the vast expanse of ocean makes even a concentration of sea power against U.S. shores highly difficult. Consequently, America has been able to neglect its armed forces and yet pursue a blustery foreign policy without much fear of war. After the War of 1812, no foreign power placed a hostile soldier on American soil, with the exception of a few raids across the Mexican-American border. For most of the 19th century, Americans thought little about foreign policy except as it affected trade and commerce.

Fortunately for the United States, Europe was preoccupied with internal matters from 1815 through 1860 and paid little attention to events in the New World. Great Britain tacitly supported the Monroe Doctrine, and no significant threats to America arose from European quarters until the 1830s. Relations between the United States and Great Britain were, however, strained by animosity left over from the Revolution and the War of 1812. As the old pro-British Federalist Party was gone, Jacksonian Democrats, who tended to be anti-British, created an atmosphere in which tension between the two nations gradually rose.

Northern Americans had always hoped for Canadian independence, partly out sympathy for a smoldering desire for independence among some Canadians, but mostly out of land greed. Occasional small rebellions in Canada were crushed by British forces, and the long, unguarded boundary made it easy for Americans to intervene in Canadian affairs. Another issue which irritated the British was the lack of copyright laws in America, which deprived British authors their rights. American publishers sent buyers to Great Britain to bring back copies of popular works, which they then published in the United States without paying royalties to the authors. British writers petitioned Congress in 1836 without result, and some writers, including Charles Dickens, came to America to publish their works in order to protect their rights. The situation was not rectified until 1891.

As a noted and popular author, Charles Dickens was fêted in America, but then had the temerity to return home and write unkindly about what he had found on this side of the Atlantic. Other visitors found almost every aspect of American life despicable, including slave auctions, lynchings, and a general lack of law and order. English visitors saw the United States as “dirty, uncomfortable and crude,” with pigs running loose in the streets of New York City; they found fault with American habits of tobacco chewing, gambling, dueling, brawling, holding religious revivals, and other social misbehavior.

American states and territories had substantial debts in England that had arisen from heavy borrowing to finance internal improvements. When Americans defaulted on those debts during the 1837 depression, the British press, already angry over copyright matters, called Americans a nation of swindlers. The British Punch declared the American eagle “an unclean bird of the vulture tribe.” Troublemakers in America stirred the pot, showing sympathy for Canadian rebels and running weapons over the border. They called the British “bloated bondsmen.” When comments of that sort were published in British and American newspapers, they made their way across the Atlantic, and it was soon said that the United States and Great Britain were “two countries separated by a common language”; each side could readily read the other’s insults.

The Caroline Affair

In 1837 a rebellion against British rule in Canada was led by a small group of malcontents. Given that it was a bad year for America economically, many unemployed Americans—not always the most upstanding citizens—headed for the border to volunteer, perhaps in hope of a reward in land. Americans had sympathy for the Canadian rebels, but were also fueled by greed (the old 1812 land hunger.) They turned weapons over to the insurrectionists. A Canadian rebel leader named MacKenzie established headquarters on Navy Island on the Canadian side of the Niagara River near the Falls to recruit Americans. The Caroline, a small steamer, carried supplies from the New York side across to Canada.

On December 12, 1837, a British raiding party sank and burned the Caroline, sending the carcass of the ship over the falls. The British Officer-in-Charge was knighted for his actions, which outraged the Americans. The Caroline was clearly un-neutral, but the British acted hastily. In making no attempt to go through U.S. authorities, they violated U.S. sovereignty. The Caroline action was insignificant, but one American was killed (on American soil), and several others were wounded.

The American Press, always quick to defend American honor, called for the “wanton act” to be avenged by blood. President Van Buren responded calmly, but forcefully; he asked Americans to quit the rebellion and sent General Winfield Scott to the border area to mediate the crisis. The New York and Vermont militia were called into service to keep order. Protests went back and forth, but the British government in London was unresponsive. The issue rankled but was unresolved.

In 1838 the Free Canada movement started up again, and several bands of “liberators” invaded Canada. Americans burned the Sir Robert Peel—a steamboat for a steamboat—shouting “Remember the Caroline!” The British authorities captured many of the interfering individuals, and some were sent to the penal colony of Australia.

President Van Buren was criticized on both sides, but he handled the crisis wisely. He published a strong proclamation to Americans to obey neutrality laws. Some U.S. insurrectionists were tried and punished, most of whom were pardoned after the 1840 election (which Van Buren lost.) General Scott personally patrolled the border, putting out little fires here and there. In any case no one in the U.S. or Great Britain really wanted war. (Some Britons, in fact, wondered whether it might be time to dump Canada.)

The issue refused to die, however. In 1840 a Canadian sheriff named McLeod was arrested over the Caroline business. He claimed to have killed the American in the Caroline raid. He was arrested and tried for arson and murder in a New York State court over strong British protests. The federal government explained that New York State had sole jurisdiction, something incomprehensible to the British, who did not understand the American federal system. Government officials in Washington attempted to intervene, but New York authorities stubbornly went ahead with the trial.

Lord Palmerston, British Prime Minister, admitted that the ship was destroyed under orders to stop American “pirates.” He said that the conviction of McLeod “would produce war, war immediate and frightful in its character because it would be a war of retaliation and vengeance.” The Canadian press grew quite belligerent—“If war must come, let it come at once.” The trial, however, was conducted without incident. Secretary of State Webster sent a message to prevent a lynching or there would be “war within ten days.” The jury, however, acquitted McLeod in twenty minutes; he had been drunk and merely boasting.

In 1842 Congress passed the Remedial Justice Act, which gave jurisdiction in international disputes to federal courts. But the states were still able to embarrass the federal government when dealing with aliens. For example, there was trouble with the Italian government over prosecutions of mafia members in New Orleans about 50 years later.

Another sore spot was the Maine-Canada boundary. The so-called “Aroostook War” broke out in 1839 from a dispute over the location of the boundary line along the Aroostook River. The exact location of the boundary had been unsettled since 1783. The British were building a road through the disputed territory to connect the frozen St. Lawrence River with the sea when they ran into some “Mainiacs” who challenged their right to impinge upon United States property. A few shots were fired, war fever erupted briefly, and war appropriations were made. Winfield Scott was again sent to the scene and arranged a truce.

In 1841 the Creole affair added new tension. The British were fighting the slave trade, and captured an American ship, the Creole, that was in hands of slave mutineers; one white passenger had been killed. The mutineers took the ship to Nassau in the Bahamas, where the British punished the murderers. However, the British granted asylum to the 130 Virginia slaves, refusing to return them to their owners in Virginia. Secretary of State Webster protested to the British and demanded return of the slaves as American property, but the British took no steps to honor Webster's demands.

By 1841 tensions were still high from the Caroline affair and other issues, but in September 1841 the new British Foreign Minister, Lord Aberdeen, sent Lord Ashburton to Washington to negotiate differences. Ashburton was a good choice. He had many American social and commercial ties, as well as an American wife. Americans saw this special mission as a “gracious” act. The English in turn liked Webster, the only Harrison cabinet member to stay on under President Tyler. Webster had been in England three years earlier and had made friends in the British government, including Lord Ashburton.

The major issue to be resolved was the Maine-Canada border dispute, which eventually became known as the “Battle of the Maps”: conflicting maps were produced on both sides, including one drawn by Benjamin Franklin, and one step of the process involved scrapping the boundaries of the Treaty of Paris of 1783. Although the United States in the initial agreement received something over half of the disputed territory, the Senate balked at the loss of land in Maine. However, historian Jared Sparks had found a map in the French archives which showed the Canada-Maine boundary marked in red. Webster had an older map which showed the same thing. The maps were used to gain consent from the senators from Maine and Massachusetts, who were in on the talks, as was President Tyler at one point.

The major issue to be resolved was the Maine-Canada border dispute, which eventually became known as the “Battle of the Maps”: conflicting maps were produced on both sides, including one drawn by Benjamin Franklin, and one step of the process involved scrapping the boundaries of the Treaty of Paris of 1783. Although the United States in the initial agreement received something over half of the disputed territory, the Senate balked at the loss of land in Maine. However, historian Jared Sparks had found a map in the French archives which showed the Canada-Maine boundary marked in red. Webster had an older map which showed the same thing. The maps were used to gain consent from the senators from Maine and Massachusetts, who were in on the talks, as was President Tyler at one point.

The four-sided negotiations (Secretary Webster, Minister Ashburton, and the Senators from Massachusetts and Maine, which had been part of Massachusetts until 1820) puzzled Ashburton, who did not see why he could not settle the matter with Webster alone; he had become frustrated with the August heat in Washington. Webster explained that when the treaty was negotiated by him and Ashburton, it would still have to be approved by the Senate in order to become effective. Webster felt that having the senators most directly concerned in on the proceedings would iron out difficulties of ratification in advance.

The British were not particularly happy with the initial agreement either, but another map suggested that Americans might have a right to the entire area. On the other hand, an earlier map could have been used to make the case that the British had a rightful claim to the entire area. In any case, the “battle of the maps” resulted in the division of the disputed territory. The four Senators helped with ratification, and the Webster-Ashburton Treaty was approved by a Senate vote of 39-9. The United States government sweetened the pill by paying Massachusetts and Maine $150,000. Lord Ashburton also drafted a formal explanation that in effect apologized for the Caroline affair and closed that matter once and for all.

Note: The Webster-Ashburton Treaty contains a lesson for future Presidents like Woodrow Wilson. His goals for establishing world peace following World War I were thwarted to some extent by the fact that he failed to take any senators or Republicans with him on his mission to negotiate the Versailles Treaty and create the League of Nations. The Senate never did ratify the treaty nor approve United states membership in the League.

Another issue under dispute concerned the exact location of the New York-Vermont boundary with Canada. Americans had been constructing a fort in the area, and the British claimed it was being built on Canadian soil. That issue was settled by use of a 1774 map and left the fort in American territory. The remaining boundary between the United States and Canada was resolved out to the area of the Lake of the Woods in northern Minnesota and thence along the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains. The Oregon territory was left under dual occupancy. In the end the United States lost 5,000 square miles in Maine but gained 6,500 square miles in Minnesota, including the rich Mesabi iron ore deposits.

Considerable disagreement also existed between the two countries over the slave trade; the British wanted the right to “visit” ships to inspect for slaves. Finally both sides agreed to keep squadrons off the African coast to enforce their own laws. This “joint police force” never worked in practice. (The film Amistad, mentioned in the previous section, also portrays some of the tensions regarding the international slave trade.)

Although the Webster-Ashburton Treaty left the Oregon boundary question open, the agreement helped pave the way for peaceful settlement of the issue in 1846. The two nations would have occasional disagreements in later years, but no real threat to peaceable relations between the former colonies and the mother country ever arose thereafter.

The history of Texas is among the most colorful histories of all American states and territories. With its diverse population of Mexican, Mexican-American, Native American and Anglo-Saxon inhabitants, its culture is rich and varied. Spain first arrived in Mexico in 1519, and Nueva Mexico was part the vast territory known as New Spain. Spanish rule in Central and South America was very different from that of British rule in North America. Where the British saw each colony as a separate political entity to be governed more or less independently, Spain tended to govern its entire empire from the center. That tradition was passed on to the Mexican government once the Mexican revolution against Spain was complete, and virtually all of Mexico was governed from Mexico City. The individual provinces of Mexico, including the province of Coahuila, of which Tejas—Texas—was a part, had very little self-determination. That situation was challenged by the arrival of Americans who immigrated to Texas in order to obtain land grants being generously offered by the Mexican government.

Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Americans began to look hungrily at the land just across their Southwest border. The Mexican government, following the lead of Spanish authorities, granted colonization rights to the American Moses Austin. In so doing they hoped to create a buffer territory against encroachment by land-hungry Americans. The Mexican government, in other words, decided to fight fire with fire. By allowing a limited number of American immigrants into Mexico under certain restrictions, they could prevent more Americans from simply seizing the territory.

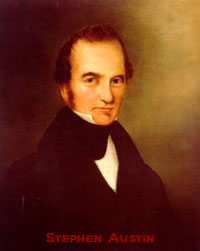

Moses Austin died before his colonization project became a reality, but the mission was taken over by his son, Stephen F. Austin. In 1821 Stephen Austin brought 300 families across Sabine River to the region along the Brazos River, where the first American colony in Texas was established. In exchange for generous land grants, the Mexican government attached certain conditions to those grants. Each settler had to agree to become a Mexican citizen, to adopt the Roman Catholic religion, and to give up the practice of slavery.

Since the Texas colony was governed loosely, much as the early American colonies had been controlled by Great Britain, the Mexican government turned a blind eye to violations of the agreements. The status of Mexican citizenship changed very little in terms of the loyalties of the American settlers; they were Americans first, Mexicans second. As far as the Catholic religion was concerned, there were no Catholic priests in the province, and therefore attendance at confession and mass could not be demanded nor controlled in any way. As to slavery, the Mexican government was willing to accept a compromise in authorizing the practice of lifetime indentured servitude. The difference between that status and slavery was, of course, only technical, but it satisfied both sides. The Texans were also obliged to pay taxes to the Mexican government, but there were no tax collectors in the Texas province, so that point was also moot.

In other words, the situation of the Americans in Texas was similar to that of the American colonists on the east coast of North America in 1760. They were treated with benign neglect, and the Texans possessed a de facto sense of self rule if not outright independence. The men and women who came to Texas tended to be a rough and ready lot. Many who emigrated were of Scots-Irish descent from the Shenandoah and other regions west of the Appalachians. Adventurous American women learned that if they came to Mexico and married a Mexican citizen, they could gain very generous land grants and have significant rights to the titles. Thus a complex society emerged, a mixture of Mexican and American along with Comanche, Apache, Kiowa and other Indian tribes on the edges of the Texas colony. They developed a small but robust society.

President John Quincy Adams tried in 1825 to purchase as much of Texas as he could get from Mexico, without success. Henry Clay also worked on the issue while Secretary of State under Adams. President Jackson appointed Colonel Anthony Butler to continue negotiations with Mexico in 1829. Jackson’s minister, Anthony Butler, tried to bribe the Mexican government. Jackson called Butler a “scamp” but left him there. Mexico was insulted by American overtures, and the negotiations went nowhere.

Stephen F. Austin: A True Statesman

Under Stephen Austin the Texas community thrived. Austin spoke fluent Spanish, played by the rules, and developed good relations with the central government in Mexico City. He insisted that the Americans who came to Mexico understand and abide by the rules under which they were granted land. Between 1824 and 1835 the Texas population grew from 2,000 to 35,000 settlers. Some of the immigrants were renegades, “one step ahead of the sheriff,” with various legal difficulties. Some were men like Jim Bowie, a fighter and gambler whose brother invented the Bowie knife. It was not surprising that the Mexican government eventually came to consider the Texians, as they were called at the time, “a horde of infamous bandits,” although the majority were decent citizens.

Under Stephen Austin the Texas community thrived. Austin spoke fluent Spanish, played by the rules, and developed good relations with the central government in Mexico City. He insisted that the Americans who came to Mexico understand and abide by the rules under which they were granted land. Between 1824 and 1835 the Texas population grew from 2,000 to 35,000 settlers. Some of the immigrants were renegades, “one step ahead of the sheriff,” with various legal difficulties. Some were men like Jim Bowie, a fighter and gambler whose brother invented the Bowie knife. It was not surprising that the Mexican government eventually came to consider the Texians, as they were called at the time, “a horde of infamous bandits,” although the majority were decent citizens.

Texas was, however, subject to the political affairs of greater Mexico. Mexico had adopted a constitution in 1824 under which the Texans believed that their rights were more or less assured. As long as they were left alone, they were free to create a society according to their own designs. When revolution began in Mexico, however, things began to change for the Texans. In 1830 the Mexican government reversed itself and prohibited further immigration into Texas. Mexican dictator Antônio Lopez de Santa Anna, somewhat after the fashion of his counterpart, King George III, decided that it was time to make the Texans toe the line. What happened in Texas is typical of situations in which people get used to doing things their own way and are suddenly forced to obey the dictates of others. The Texans rebelled; Santa Anna vowed to make them behave.

As mentioned above, Texas was something of a refuge for Americans who had reason to leave home. One such emigrant was Sam Houston, a colorful figure who could be considered the most significant figure in American history between 1840 and 1860. A close friend of Andrew Jackson, he had fought with the general during the War of 1812. Houston was elected governor of Tennessee in 1828. He married Eliza Allen, a member of a prominent Tennessee family, but the marriage ended quickly and badly. Details have remained murky, but the Allen family apparently pressured Houston to leave the state. In any case, Houston resigned his governorship and left Tennessee.

For a time Houston dwelt among the Cherokee Indians, who adopted him as a son. He was known as “the Raven” because of his jet black hair. He married a Cherokee woman and represented Cherokee interests with the United States government. It was that business that eventually took Houston to Texas. The Cherokee were also aware of Houston’s fondness for alcohol—some of them had another Indian name for him: Big Drunk. (He once bet a friend on New Year’s Day that he could quit drinking for a year, and he almost made it to February.)

As a natural leader, Sam Houston quickly rose to prominence in the rough-edged territory. He married his third wife, who helped him overcome his drinking problem. The rebellious Texans declared independence from Mexico in 1836 and, recognizing Houston’s military experience, named him Major General of the Army of Texas. They also created the rudiments of a national government, using the American Declaration of Independence and Constitution as models.

The Texans’ task was as difficult as that of the patriots of 1776, and they had fewer resources. But they were willing to fight. After a few brief skirmishes, Mexican dictator Santa Anna personally led an army of several thousand well trained troops into Texas to put down the insurrection. The Texas army, which never numbered more than 800 and had little experience in war, faced a daunting task. Santa Anna, however, unwittingly aided the Texan cause by branding the revolutionaries as outlaws and criminals and treating them as such. While the Texans were deciding on their Declaration of Independence and considering the political future of Texas, Santa Anna was slaughtering Texans and giving them no quarter.

The Alamo. The most famous clash took place at an old Spanish mission at San Antonio de Bexar known as the Alamo early in 1836, the last year of the administration of Andrew Jackson. At the Alamo fewer than 200 Texans under Lieutenant Colonel William Travis held off about 3,000 Mexicans for 13 days, inflicting heavy casualties on the attackers. The Mexican army eventually overpowered the fortress, and all the Texan defenders died, including Travis, Jim Bowie, and former Congressman Davy Crockett. Santa Anna then had their bodies burned rather than giving them a Christian burial. Weeks later, at Goliad, 400 Texans surrendered to one of Santa Anna’s subordinate generals, and on Santa Anna’s order, 300 of them were murdered. The Texans’ war cry became “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!”

The Alamo. The most famous clash took place at an old Spanish mission at San Antonio de Bexar known as the Alamo early in 1836, the last year of the administration of Andrew Jackson. At the Alamo fewer than 200 Texans under Lieutenant Colonel William Travis held off about 3,000 Mexicans for 13 days, inflicting heavy casualties on the attackers. The Mexican army eventually overpowered the fortress, and all the Texan defenders died, including Travis, Jim Bowie, and former Congressman Davy Crockett. Santa Anna then had their bodies burned rather than giving them a Christian burial. Weeks later, at Goliad, 400 Texans surrendered to one of Santa Anna’s subordinate generals, and on Santa Anna’s order, 300 of them were murdered. The Texans’ war cry became “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!”

In the 2004 film, The Alamo, with Dennis Quaid and Billy Bob Thornton, a lot of verbal sparring preceded and followed the standoff at the Alamo itself. Some critics would have preferred to see less talk and more action, but the political machinations going on off the battlefield were in many ways just as important as what happened at the Alamo, if not more so. The situation between Texas and Mexico was in certain respects more complex than that of the American colonies; for the inhabitants of Texas, the Americans, had voluntarily sworn allegiance to Mexico, and had moved into Mexican territory to make their homes.

anta Anna’s overconfidence and arrogance led him to carelessness. Sam Houston was sharply criticized for failing to go to the relief of the Alamo or to attack the Mexican Army. He bided his time, waited for the opportunity, and when it came, he struck with startling swiftness. Houston’s Texans caught up with Santa Anna on the San Jacinto River, near the present-day city of Houston, found the Mexicans unprepared. The Texans swept over the Mexican army and won a stunning victory in 18 minutes, suffering few casualties themselves. With their anger over the Alamo and Goliad very much still present, the Texans inflicted severe casualties on the Mexicans.

Santa Anna escaped during the battle but was captured and brought to Houston. Many Texans wanted to execute him on the spot for his crimes against prisoners at Goliad. Instead, Houston forced Santa Anna, under considerable duress, to grant Texas independence. Santa Anna, fearing for his life, signed a treaty and ordered the remainder of the Mexican army out of Texas. The Mexican Congress later repudiated the treaty and declared that Santa Anna was no longer president. The general eventually returned to Mexico, but after various political intrigues, he was exiled to Cuba in 1845. A year later he was allowed to return when the war with the United States began in 1846.

The United States soon recognized Texas independence, and the Lone Star Republic was born. Sam Houston was elected as its first president, with Stephen Austin as Secretary of State. At that juncture the future of Texas turned on the issue of whether or not Texas would be annexed to the United States. Given America’s propensity to gather up land whenever and wherever it was available, the outcome seemed to a certain extent foreordained. But Presidents Jackson, Van Buren and Tyler wanted to avoid war with Mexico. It was likely that if Texas were annexed, war would be the result. The issue of slavery in Texas was also a factor. Nevertheless, Texas pursued her goal of annexation, actually using a veiled threat to perhaps join Great Britain or France if the United States continued to spurn her approaches. Frustrated Sam Houston wrote a letter to Jackson:

The United States soon recognized Texas independence, and the Lone Star Republic was born. Sam Houston was elected as its first president, with Stephen Austin as Secretary of State. At that juncture the future of Texas turned on the issue of whether or not Texas would be annexed to the United States. Given America’s propensity to gather up land whenever and wherever it was available, the outcome seemed to a certain extent foreordained. But Presidents Jackson, Van Buren and Tyler wanted to avoid war with Mexico. It was likely that if Texas were annexed, war would be the result. The issue of slavery in Texas was also a factor. Nevertheless, Texas pursued her goal of annexation, actually using a veiled threat to perhaps join Great Britain or France if the United States continued to spurn her approaches. Frustrated Sam Houston wrote a letter to Jackson:

“Now my venerated friend, you will perceive that Texas is presented to the union as a bride adorned for her espousal. But, if, now so confident of the union, she should be rejected, her mortification would be indescribable. She has sought the United States, and this is the third time she has consented. Were she now to be spurned it would forever terminate expectation on her part, and it would then not only be left for the United States to expect that she would seek some other friend, but all Christendom would justify her course dictated by necessity and sanctioned by wisdom.”

The Lone Star Republic lasted ten years and gained a further identity, so that when Texas finally did join the union, it came in with a history of its own. Texans have held that history in high regard ever since. The Alamo remains a Texas shrine, as does the San Jacinto battlefield. The capital is named for Stephen Austin, the largest city for Sam Houston, and other places in Texas also recall the names of heroes of the Texas Revolution. As feared, however, the annexation of Texas led more or less directly to war with Mexico in 1846.

Sam Houston’s colorful career would continue through the beginning of the Civil War. He had served as governor of two states, Tennessee and Texas, as President of the Republic of Texas, which remained independent for about ten years, and at one point during his interesting life he served as Cherokee Indian Ambassador to the United States. His political career finally came to an end when, as governor of Texas, he refused to support secession. He was ousted from office and burned in effigy in 1863. (Having worked hard to get Texas into the Union, he was not about to lead it out.) Nevertheless he remains an American and Texan hero.

(An excellent account of the history of Texas through 1865 is H.W. Brands, Lone Star Nation, New York: Doubleday, 2004. See also T.R. Fehrenbach, Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans, New York: Macmillan, 1968.)

Manifest Destiny and Mexico

After rejecting the annexation of Texas in the 1830s, the United States stood by as the people of the Republic of Texas sought to create favorable foreign relations on their own. Texas signed treaties with France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Great Britain and was able to secure loans for commercial development. Mexico continued to threaten the Lone Star Republic, and in 1843 President Santa Anna declared that any attempt to annex Texas to the United States would be considered an “equivalent to a declaration of war against the Mexican Republic.” Despite its good relations and favorable treatment from Great Britain, Houston still desired annexation, but only on the condition that the United States would provide military protection in case of a Mexican attack. President Tyler submitted an annexation Treaty to the Senate, but it was rejected; President Tyler nevertheless kept his promise to provide protection and sent ships to the Gulf of Mexico and troops to the Texas border.

Congressmen John Quincy Adams, by now an open advocate of the abolition of slavery, and others maintained that no one had the power to annex a foreign nation to the United States. The issue was slavery—a free Texas would hem in slavery in the South and prevent expansion to territories west of Texas; a slave Texas would expand the scope of slavery enormously because of the size of the state. There was even talk of dividing Texas into several slave states. Great Britain was interested in Texas and was considering an offer to buy out all the slaves in exchange for other concessions.

The 1844 Election. The presidential campaign of 1844 turned on the issue of expansion, both in Texas and in the Oregon territory. The Whigs nominated Henry Clay for president and the Democrats James K. Polk of Tennessee along with George M. Dallas of Pennsylvania as the vice presidential candidate. A third party, the Liberty Party, whose chief issue was anti-slavery, nominated James Birney. Henry Clay took a stance against the annexation of Texas, and his anti-expansion position cost him the election, although it was very close. In fact, the outcome in the electoral college turned on the results in New York State, where Birney took enough votes away from Clay to throw the election to James K. Polk, Tennessee’s “Young Hickory.”

With the election results clearly favoring the annexation of Texas, President Tyler recommended that Texas be annexed to the United States by a joint resolution of Congress. He cited the election results as one reason and possible intervention by Great Britain as an additional justification. The joint resolution was used to get around the necessity of a two thirds vote in the Senate required for treaty ratification, a ploy which was later used in other similar cases. (Hawaii was annexed by a joint resolution in 1898 when an annexation treaty could not achieve a two-thirds vote.) The resolution was eventually passed. It provided that Texas would immediately become a state, bypassing territorial status, as soon as its boundary was officially settled and its constitution submitted to the President of the United States. The act also provided that the new state might be divided into as many as four additional states and that all its defense works and property be transferred to the United States.

With the election results clearly favoring the annexation of Texas, President Tyler recommended that Texas be annexed to the United States by a joint resolution of Congress. He cited the election results as one reason and possible intervention by Great Britain as an additional justification. The joint resolution was used to get around the necessity of a two thirds vote in the Senate required for treaty ratification, a ploy which was later used in other similar cases. (Hawaii was annexed by a joint resolution in 1898 when an annexation treaty could not achieve a two-thirds vote.) The resolution was eventually passed. It provided that Texas would immediately become a state, bypassing territorial status, as soon as its boundary was officially settled and its constitution submitted to the President of the United States. The act also provided that the new state might be divided into as many as four additional states and that all its defense works and property be transferred to the United States.

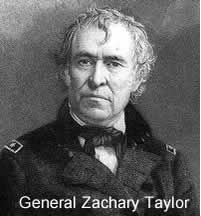

President Polk and Mexico. When Congress passed a joint resolution for the annexation of Texas, Mexico severed diplomatic relations with the United States. Furthermore, Mexico claimed the legitimate boundary between Texas and Mexico was at the Nueces River, over one hundred miles north of the Rio Grande. In May 1845 President Polk ordered the commander of United States forces in the Southwest, General Zachary Taylor, known as “Old Rough and Ready,” to move his troops into Texas and position himself “on or near the Rio Grande River.” General Taylor initially positioned himself just south of the Nueces River near Corpus Christi. In early 1846 he built Fort Texas across the Rio Grande from the Mexican city of Matamoros and blockaded the river.

President Polk had a goal upon taking office of the acquisition of California and New Mexico. He sent John Slidell on a secret mission to Mexico with an offer to purchase the territories. Polk was prepared to offer up to $50 million for the area. Although the Mexican government had initially agreed to meet with Slidell, when they found out that his mission was not only about the Texas boundary but also about the western territories, the Mexican government refused to receive him. (See Robert W. Merry, A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War and the Conquest of the American Continent, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009)

By April 1846 a Mexican force had positioned itself opposite Taylor's troops on the Rio Grande. General Mariano Arista, who had several thousand troops in Matamoros, sent a cavalry force across the Rio Grande upriver from Matamoros. This move precipitated a clash with American troops, resulting in eleven American deaths. President Polk then sent a message to Congress, stating that the United States had a “strong desire to establish peace with Mexico on liberal and honorable terms.” He added, “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory, and shed American blood upon the American soil.” After reviewing the events leading to the crisis, including the rejection of the Slidell mission, he stated:

The grievous wrongs perpetrated by Mexico upon our citizens throughout a long period of years remain unredressed, and solemn treaties pledging her public faith for this redress have been disregarded. A government either unable or unwilling to enforce the execution of such treaties fails to perform one of its plainest duties.

Abolitionists claimed that Polk’s provocative action in sending Taylor to the Rio Grande was in itself an act of war; an anti-war movement grew, especially in the Northeast. Henry David Thoreau wrote an essay on “Civil Disobedience” and refused to pay his taxes, and Congressman John Quincy Adams opposed the war in the House of Representatives. The new Whig Congressman from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, introduced a set of “Spot Resolutions,” demanding that the president reveal the exact spot on which blood had been shed, meaning on Mexican or American soil. This very unpopular war became known as “Mr. Polk’s War” primarily because of the fear of the extension of slavery. The vote for war was 174-14 in the House and 40-2 in the Senate, but antiwar sentiment ran deep, especially among Northern Whigs and abolitionists. Once President Polk put soldiers in harm’s way, it was difficult for opponents to muster votes against the war.

The Wilmot Proviso. As soon as the United States declared war against Mexico in 1846, anti-slavery groups wanted to make sure that slavery would not expand in the case of an American victory. Congressman David Wilmot opened the debate by introducing a bill in Congress, the “Wilmot Proviso,” that would have banned all African-Americans, slave or free, from whatever land the United States took from Mexico, thus preserving the area for white small farmers. It passed the House, but failed in the Senate. John C. Calhoun argued that Congress had no right to bar slavery from any territory, an issue that would surface again after the war. Others tried to find grounds for compromise between Wilmot and Calhoun.

President Polk suggested extending the 36-30 line of the Missouri Compromise to the Pacific coast. In 1848 Lewis Cass proposed to settle the issue by “popular sovereignty”—organizing the territories without mention of slavery and letting local settlers decide whether their territory would be slave or free. It seemed a democratic way to solve the problem and it got Congress off the hook. This blend of racism and antislavery won great support in the North, and although the Wilmot Proviso was debated frequently, it never passed. The battle over the Proviso foreshadowed an even more urgent controversy once the peace treaty with Mexico was signed. It would be debated again in the years ahead.

President Polk had additional political problems with the war besides Mr. Wilmot’s proposal. Both senior generals—Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott—were Whigs, and the nation had already shown a propensity to raise successful generals to high office. But the demands of war outweighed the political issue, and both generals led American troops in the conflict. As mentioned above, opposition to and support for the war tended to divide along political lines, and the conduct of the war had strong political overtones.

Campaigns in Northern Mexico. After war was declared, General Taylor moved to relieve the besieged Americans at Fort Texas, which had been renamed Fort Brown in honor of its fallen commander. Along the way he fought two successful battles against numerically superior Mexican forces at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. He then crossed the Rio Grande and occupied Matamoros, where he undertook to train several thousand volunteers who had recently joined his army. Meanwhile, General John Wool set out from San Antonio toward the Mexican town of Chihuahua, farther to the west. A third force under Colonel Stephen Kearny set out from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for California. A portion of Kearny’s command under Colonel Alexander Doniphan was detached and sent across the Rio Grande at El Paso toward Chihuahua, where they defeated a force of Mexican militia. General Wool’s force eventually joined Taylor’s command.

Campaigns in Northern Mexico. After war was declared, General Taylor moved to relieve the besieged Americans at Fort Texas, which had been renamed Fort Brown in honor of its fallen commander. Along the way he fought two successful battles against numerically superior Mexican forces at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. He then crossed the Rio Grande and occupied Matamoros, where he undertook to train several thousand volunteers who had recently joined his army. Meanwhile, General John Wool set out from San Antonio toward the Mexican town of Chihuahua, farther to the west. A third force under Colonel Stephen Kearny set out from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for California. A portion of Kearny’s command under Colonel Alexander Doniphan was detached and sent across the Rio Grande at El Paso toward Chihuahua, where they defeated a force of Mexican militia. General Wool’s force eventually joined Taylor’s command.

With his army increased by volunteers, Taylor moved up the Rio Grande on the Mexican side and established a base for a march on the city of Monterrey. The city was well fortified on the north by a strong citadel. Taylor divided his army, sent troops to cut off the city from the rear and attacked from several directions while using artillery and mortars to attack the citadel. Fighting within the city was heavy, but following a four day-siege, the enemy surrendered. Although Taylor had been successful since the beginning of his campaign, he was still a long way from Mexico City. He proceeded to advance further into Mexico in the direction of San Luis Potosi, where General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna was assembling a large army. Santa Anna had been released from exile by President Polk in the hope that the general would be willing to negotiate a truce. Santa Anna, however, accused of having betrayed his country to the Americans, chose to fight.

Santa Anna advanced northward with the intention of driving Taylor out of Mexico. Taylor wisely withdrew to a strong defensive position near Buena Vista. With his force of less than 5,000 men, he awaited the attack of Santa Anna's 15,000 soldiers. Santa Anna ordered an unconditional surrender, but Taylor refused. Though outnumbered, Taylor’s army withstood repeated Mexican attacks, inflicting heavy casualties on their enemies, and on February 23, 1847, Santa Anna began to withdraw toward Mexico City. The hardest battle of the war was won, the war in northern Mexico was over, and the area along the Rio Grande was secure.

Meanwhile, The U.S. Navy had captured the port of Tampico. General Winfield Scott was authorized to conduct a landing at Vera Cruz in anticipation of a march on Mexico City. Scott arrived in Mexico in December 1846 and detached several thousand of Taylor’s troops and ordered them to march to Tampico to take part in the Vera Cruz operation. Taylor was outraged; he believed that Scott’s plan was politically motivated. As Scott was the senior general, with service dated back to the War of 1812, Taylor had to follow his orders.

General Scott’s Vera Cruz Campaign

In February 1847 General Scott landed his force of about 10,000 men at a position south of Vera Cruz in a landing that was essentially unopposed. Assisted by naval batteries that shelled the city, Scott’s army achieved the surrender of Vera Cruz with only light American losses. On April 8 Scott set off along the National Road toward Mexico City. Santa Anna had assembled a force of about 13,000 to block Scott’s advance at Cerro Gordo. Using the skillful reconnaissance information gained by Captains Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan, Scott flanked the Mexican force and routed Santa Anna. By May 15th Scott was 80 miles from Mexico City, where he paused, awaiting fresh troops. Once reinforced, Scott continued his well-organized advance and defeated the Mexican army once more at the battles of Contreras and Churubusco, driving to within 5 miles of the capital.

In February 1847 General Scott landed his force of about 10,000 men at a position south of Vera Cruz in a landing that was essentially unopposed. Assisted by naval batteries that shelled the city, Scott’s army achieved the surrender of Vera Cruz with only light American losses. On April 8 Scott set off along the National Road toward Mexico City. Santa Anna had assembled a force of about 13,000 to block Scott’s advance at Cerro Gordo. Using the skillful reconnaissance information gained by Captains Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan, Scott flanked the Mexican force and routed Santa Anna. By May 15th Scott was 80 miles from Mexico City, where he paused, awaiting fresh troops. Once reinforced, Scott continued his well-organized advance and defeated the Mexican army once more at the battles of Contreras and Churubusco, driving to within 5 miles of the capital.

President Polk, meanwhile, had sent Nicholas Trist, the chief clerk of the State Department, to accompany Scott’s army with authorization to negotiate peace terms with the Mexican government. Scott was not especially welcoming to Trist, feeling that as commander on the ground, he himself was responsible for negotiations. Nevertheless, after some discussion, Trist was allowed by Scott to negotiate an armistice with the Mexican government. When the offer was rejected, Scott proceeded to march on the capital.

In their final assault on Mexico City, Scott’s soldiers and Marines attacked the fortress of Chapultepec and eventually scaled the rocky walls and arrived at the summit. The Americans moved into the city, raised their flag over the National Palace, and a battalion of Marines occupied the “Halls of Montezuma.”

Victory in Mexico: The Superiority of American Arms

The Regular U.S. Army numbered only about 5,000 officers and men at the outbreak—one fourth the size of the Mexican Army. American volunteers from the West were a raunchy crew—ill disciplined and dirty—but they fought well. Mexico was also poorly prepared. Their artillery was so outdated that American soldiers were able to dodge Mexican cannon balls that often fell short and bounced along the ground.

The war was also a training ground for future Civil War generals: U.S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, William T. Sherman, George G. Meade, George B. McClellan, Thomas J. Jackson, James Longstreet, Braxton Bragg, Joseph Johnston, and many others got their first taste of war in Mexico. Note: Friendships formed, and knowledge of their compatriots’ military skills as well as shortcomings, played a part in the Civil War, 1861-1865.

The war was also a training ground for future Civil War generals: U.S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, William T. Sherman, George G. Meade, George B. McClellan, Thomas J. Jackson, James Longstreet, Braxton Bragg, Joseph Johnston, and many others got their first taste of war in Mexico. Note: Friendships formed, and knowledge of their compatriots’ military skills as well as shortcomings, played a part in the Civil War, 1861-1865.

Winfield Scott’s Campaign against the Mexican capital was one of the most brilliant in American history. He avoided direct assaults and used engineers and reconnaissance to flank defended positions. At the outset of the campaign, the Duke of Wellington, victor over Napoleon at Waterloo, made a dire prediction: “Scott is lost.” For once, the Iron Duke was wrong.

The California Campaigns. While Generals Taylor and Scott were busy in Mexico, the situation in California was one of confusion. Americans had begun to settle in California in the 1840s, though the population remained heavily Mexican and Native American. In that age of faulty communication, an American naval officer landed a force in Monterey in 1842 and raised the American flag. President Tyler disowned the action and apologized to the Mexican government.

In 1846 Captain John C. Frémont led an expedition into Northern California. He found himself in the midst of a controversy involving Mexican authorities in California that stemmed from the Revolution in Mexico. American settlers in California attacked a Mexican detachment and proclaimed the “Bear Flag Republic,” declaring the American settlements in California to be independent. Frémont joined the rebellion, and the rebels were soon joined by another force under Navy Commodore John D. Sloat. Sloat raised the flag over Monterey and proclaimed that California was part of the United States.

Mexican citizens rebelled against the American authorities, and Americans were driven out of Southern California. Meanwhile, the expedition led by Colonel Stephen W. Kearny left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, marched to New Mexico, where he proclaimed the region to be part of the United States, and proceeded on to California. Once in California Kearny joined forces with Commodore Robert Stockton, who had replaced the ailing Commodore Sloat. The combined American units soon defeated the remaining Mexican forces in California.

When the fighting ceased, a complicated quarrel erupted among Kearny, Frémont and Stockton over the establishment of a government. Frémont was eventually court-martialed and found guilty of failing to obey the orders of Colonel Kearny, but president Polk ordered him restored to duty. Frémont resigned from the Army and his case was taken up by his father-in-law, SenatorThomas Hart Benton. Frémont's career was far from over: He would become the first Republican Party candidate for president in 1856.

The victory settlement made California part of the United States. The discovery of gold in Sutter's mill in 1848 would soon lead to the well-known gold rush, which by 1850 would make California ready for statehood. The final treaty signed between Frémont and the Mexican leaders granted generous terms to all Mexicans living in California.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Following the occupation of Mexico City, Santa Anna retreated to the suburb of Guadalupe Hidalgo and stepped down from the presidency. An interim government notified Nicholas Trist that it was prepared to negotiate a peace settlement. Although Trist had received orders for his recall from President Polk, he took Scott's advice and decided that since he was on the spot, he would go ahead and negotiate a settlement. Scott, meanwhile, had asked to be relieved, feeling his authority had been undercut by the Trist mission. The president was furious with both Trist and General Scott for violating his instructions. “Polk was prepared to oblige the general while also placing him before a court-martial—and tossing out Trist for good measure.”

Although Trist was acting contradictory to Polk’s instructions, he nevertheless settled on excellent terms. Mexico gave up all claims to Texas above the Rio Grande and ceded New Mexico and California, which included parts of Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming to the United States. The United States agreed to pay $15 million to the Mexican government and assume over $3 million of American citizens’ claims against Mexico. The Rio Grande was settled as the boundary of Texas and then westward to the Pacific.

Polk and was reluctant to submit the treaty to the Senate. Nevertheless, he wanted to avoid what was becoming known as the “all Mexico” movement, the notion that the United States should take over the entire Mexican nation. Amendments to that effect were never passed, however, and the Senate finally ratified the treaty by a vote of 38 to 14. The Mexican War was over. The territory which eventually comprised the lower 48 states of the United States was complete except for a small strip along the southern border of New Mexico and Arizona, which was purchased on behalf of the United States by James Gadsden in 1853. (The area was considered a favorable route for a transcontinental railroad from New Orleans to Southern California.)

Legacy of the Conflict. The cost of the Mexican-American War to America was $100 million. In the course of the fighting, 1,721 soldiers were killed in action, 4,102 were wounded in action, and 11,500 died of disease. The Mexican Cession brought in over 500,000 square miles of land, and with Texas, well over one million square miles. The idea of “manifest destiny” was partially realized, and the military victories brought the two Whig generals into public favor. Zachary Taylor was elected president in 1848, and Winfield Scott was defeated by Franklin Pierce in 1852. Scott was the last Whig to run for high public office as the party disintegrated and was soon replaced by the Republicans.

Controversy over the Mexican-American War did not subside with the cessation of hostilities. Many claimed that the treaty was forced on Mexico and that $15 million was a small price to pay for half a million square miles. By contrast the United States later paid Texas $10 million for eastern New Mexico. On the other hand, the U.S. could have taken any or all of Mexico without payment, but chose not to.

Among those who criticized the Mexican-American War was Captain Ulysses Grant. He saw the war as a political move, though he acknowledged that war and politics often went hand in hand. In his Memoirs the future U.S. president wrote:

For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the [annexation of Texas], and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. … The occupation, separation and annexation were, from the inception of the movement to its final consummation, a conspiracy to acquire territory out of which slave states might be formed for the American Union. …

It is to the credit of the American nation, however, that after conquering Mexico, and while practically holding the country in our possession, so that we could have retained the whole of it, or made any terms we chose, we paid a round sum for the additional territory taken; more than it was worth, or was likely to be, to Mexico. (U.S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. Various Editions. First published in 1885.)

The Oregon Boundary Dispute

The Oregon Territory was the located in the region west of the continental divide in the Rocky Mountains. It lay between the 42nd parallel, the northern boundary of California, and the 54°-40’ line, the southern boundary of Alaska, including all or parts of future states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming and Montana and the Canadian province of British Columbia. Both sides had long-standing claims, the claims of the United States having originated with the Lewis and Clark expedition. Since the era of the American Revoltution that territory had been claimed by both the United states and Great Britain, but in hte 1840s the issue was fianlly recolved.

More About the Oregon Boundary dispute.

James Polk’s Legacy. James K. Polk had emerged as a dark horse for the nomination of the Democratic Party for President in 1844. Although he had been Speaker of the House and governor of Tennessee, he was relatively unknown. He had four major goals for his administration to accomplish: to lower the protective tariff; to resolve the Oregon boundary dispute; to restore the independent treasury; and to acquire New Mexico and California. He achieved all those goals, thus becoming a very successful president in terms of his own intentions. He also prosecuted the Mexican War successfully, despite considerable domestic opposition, setting aside political considerations regarding his military commanders. Yet the Whig party was still strong, and therewas much discontent in parts of the country over Texas, the Mexican Cession, and other issues. Polk had promised to serve only one term, and he was exhausted after his four years in office. His retirement lasted only three months; he died in June 1849.

The 1848 Election. As the slavery issue still rankled, the Democratic Party threatened to split apart along North-South lines. The North rejected the extension of the Missouri Compromise line as too beneficial to Southern interests. President Polk kept his promise not to run for an additional term, even though his record was solid. (His turbulent four years in the White House had exhausted “Young Hickory”; he died three months after leaving office.) The Democrats sought a new candidate and finally nominated Lewis Cass of Michigan, who had coined the phrase “squatter sovereignty” or “popular sovereignty,” an idea that avoided a direct confrontation over the issue of slavery in the territories by leaving it up to the settlers themselves to decide. For all but the abolitionists, there was considerable support for popular sovereignty.

The Barnburners—Democrats discontented over the slavery issue—walked out and formed the Free-Soil Party, which nominated Martin Van Buren, who favored the Wilmot Proviso, and Charles Francis Adams, son of John Quincy Adams. The old Liberty Party of 1844 joined the Free-Soilers. Popular sovereignty found support among anti-slavery forces, who assumed that the territorial settlers would have a chance to prohibit slavery before it could get established. It was unacceptable, however, to those who wanted definite limits placed on the expansion of slavery.

Daniel Webster was the natural choice of the Whigs, but a military hero was too appealing—it had worked for the Whigs in 1840 with Benjamin Harrison. The Whigs, who had no platform, nominated “Old Rough and Ready,” General Zachary Taylor, who had no discernible political positions on almost any public issue. He had never held elective office. Born in Virginia and raised in Kentucky, Taylor was a relative of both James Madison and Robert E. Lee. His running mate was Millard Fillmore of New York, selected to balance the ticket since he came from a non-slave state. Taylor promised that there would be no executive interference with any proposed congressional legislation. With the discontented Democrats, now Free-Soilers, again taking votes in key states, General Taylor won the election, thus realizing President Polk's fears of a Whig general winning the White House with a minority of the popular vote.

The California Gold Rush

When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, thousands of Americans began flocking to California’s gold fields in 1849, creating demand for a territorial government. There were few slaves in California, though more than in New Mexico and Utah combined. Although California passed “sojourner” laws that allowed slaveholders to bring slaves and keep them for a time, slavery was not an admission issue. With slavery recognized and protected in the Constitution, the issue of slavery in states where it already existed was, for all but staunch abolitionists, not a serious issue. The issue of slavery in territories not yet states was a very big issue, however. When Californians submitted an antislavery constitution with their request for admission, Southerners were outraged because the admission of California would give the free states majority control of the Senate.

President Zachary Taylor proposed to settle the controversy by admitting California and New Mexico as states without the prior organization of a territorial government, even though New Mexico had too few people to be a state. The South reacted angrily and called for a convention of the slave holding states to meet at Nashville. Their purpose was to discuss the issue of slavery, with some more radical elements prepared to consider secession. Because only the radical “fire eaters” were prepared to go that far, only nine states sent representatives to the meetings, which took place in 1850. Since what became known as the 1850 Compromise was already being debated in Congress, nothing was formally decided; yet the Nashville Convention was a harbinger of greater problems ahead.

On the eve of the new decade, the slavery issue, which had caused relatively few serious problems since the Compromise of 1820, was about to take center stage. The debate over the issue of slavery in the newly acquired territories would be the dominant issue during the 1850s. The decade would also see the demise of the greatest leaders of the second generation of American statesmen—Clay, Calhoun and Webster. A New generation headed by Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln, both of Illinois, would take their place.

(James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. This Volume VI of the Oxford History of the United States is considered the best single volume treatment of the Civil War.)

| Expansion_& Manifest Destiny Home | Updated October 1, 2019 |