Important Battles of World War II: Europe

It is worth keeping in mind that World War II was actually two wars fought simultaneously. The United States first declared war on Japan, and the fighting in the Pacific involved the United States Armed Forces along with those of China, the British Empire and the Netherlands, all of whom had extensive interests in Asia. Nevertheless, military and political leaders both in Great Britain and United States quickly concluded that the greater threat came from Germany and Italy, and additional planning led to the adoption of a "Germany first" posture. The fact that the Soviet Union was already engaged against Germany at the time when the United States entered the war meant that the Russians could absorb a major burden in the fighting while US and British Armed Forces prepared for their assault on Western Europe. Realizing that an invasion of the European continent was not possible in the first years of the war, the American and British staffs turned their attention first to Italian and German forces in North Africa.

The fact that the Soviet Union occupied the bulk of Germany's Armed Forces during the early war years made it possible for the allies to build up the forces preparatory to an assault on the European continent along the coast of France. Had Germany managed to conquer the Soviet Union, it is likely that the allies could not have succeeded in their invasion in 1944. Because the German threat against Stalin's armies was so severe, the Soviet Union did not enter the war against Japan until after Germany had surrendered. At the Yalta conference in 1945 Stalin agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan three months after Germany surrendered. Stalin kept that pledge, but by that time the first atomic bomb had already been dropped on Hiroshima.

The North African Campaign: Operation Torch: U.S. Troops Land in North Africa

Although the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor came as a shock to most Americans, it cannot be said that America was completely unprepared for war. The first peacetime draft in American history had been instituted in 1940, and the size of the army and navy were being expanded. New equipment was also being tested and built. Americans had watched nervously as Germany overran Poland, Denmark, Norway, and France and were then stunned when Germany turned and invaded Russia in the summer of 1941 just months before Pearl Harbor. Despite the growing America first movement, few thought that America would be able to avoid war indefinitely.

Although the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor came as a shock to most Americans, it cannot be said that America was completely unprepared for war. The first peacetime draft in American history had been instituted in 1940, and the size of the army and navy were being expanded. New equipment was also being tested and built. Americans had watched nervously as Germany overran Poland, Denmark, Norway, and France and were then stunned when Germany turned and invaded Russia in the summer of 1941 just months before Pearl Harbor. Despite the growing America first movement, few thought that America would be able to avoid war indefinitely.

Being somewhat prepared for war and being in a war are two different things. With the attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war on the United States a few days later, America and her British allies were facing a two-front war of huge proportions. The joint American and British staffs quickly adopted a policy of Germany first, based on a prior understanding between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill during their conference in Newfoundland and August, 1941Hitler’s Luftwaffe was pounding Great Britain. Although much of the British army had been spared by the “Miracle of Dunkirk,” Britain was stretched very thin.

Reluctantly or not, the United States and Great Britain had accepted the Soviet Union as an ally in the fight against Nazi Germany. From the beginning, Soviet Premier Stalin urged his American and British Allies to open a second front to take pressure off the Russian armies being driven back by Hitler’s legions. Plans called for an eventual cross-channel invasion against the continent of Europe, but in 1942 such a move was out of the question.

Reluctantly or not, the United States and Great Britain had accepted the Soviet Union as an ally in the fight against Nazi Germany. From the beginning, Soviet Premier Stalin urged his American and British Allies to open a second front to take pressure off the Russian armies being driven back by Hitler’s legions. Plans called for an eventual cross-channel invasion against the continent of Europe, but in 1942 such a move was out of the question.

Thus the background was established for Operation Torch. Lieutenant General Dwight Eisenhower, who had been a major only a few years before, suddenly found himself in command of the first American offensive operation against Hitler’s Germany in World War II. The British had been fighting the Italians and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps on that continent throughout 1942, and the joint staffs decided that the first American operation would be an invasion of western North Africa. Although North Africa was removed from the continent of Europe, control of the Mediterranean was considered vital to the British. Thus securing North Africa was strategically important.

The landings in North Africa began on November 8, 1942. At first the Americans fared badly. They were untested in battle, and had equipment that was not yet up to the combat standards of a fast, mechanized mobile war. At the Battle of Kasserine Pass the Americans suffered a humiliating defeat under poor leadership. Generals George S. Patton and Omar Bradley, however, set to weeding out incompetent commanders and began to restore the morale and combat effectiveness of the American troops.

With Field Marshal Montgomery’s great victory at El Alamein in May 1943 and the Americans applying more pressure on the German armies to the west, North Africa was finally secured. The fighting in North Africa for the American army can be seen as a sort of on-the-job training exercise, though it was fierce and brutal fighting all the same. General Rommel was taken back to Germany and eventually given command on the Western front. General Patton went on to command the U.S. Third Army, one of America’s superior fighting units during the war, and General Eisenhower rose to the position of Supreme Commander of all Allied Forces in Europe. With North Africa secured, the next target for the Allies was Italy, which would be reached via an interim assault on the island of Sicily.

Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944

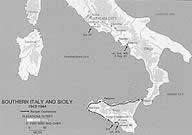

Because Italy’s military forces were far from as powerful as those of Germany, the decision to continue the advance through Italy—the so-called “soft underbelly” of Europe—made sense. The Italian Army had suffered large losses in North Africa, including a number of its best divisions. The Americans were less enthusiastic about attacking Sicily than the British, whose focus was on maintaining control of the Mediterranean to ensure contact with the Middle East. Sicily was heavily defended, and therefore the German staff was surprised when Sicily was attacked.

Operation Husky, the attack on Sicily, involved two airborne divisions and eight ground divisions that would land from the sea. The airborne operations, always complicated and difficult, did not fare well, but the landings on the south coast of Sicily were very successful. General Patton’s Third Army advanced up the western side of the island while British General Montgomery’s forces advanced east of Mount Etna; both armies were advancing toward Messina on the northeastern tip of the island of Sicily, just across the Strait of Messina from the toe of the Italian boot. German and Italian resistance was stiff in the mountainous terrain, which required the Allies to use a series of amphibious “hooks” to get around heavily defended areas. The campaign in Sicily began on July 9, 1943. By August 11 the German and Italian forces had evacuated their remaining troops and equipment to the Italian peninsula as Patton and Montgomery entered Messina.

The capture of Sicily did no serious harm to the German and Italian forces, most of which were evacuated, but it did cause the Italian government to rethink its loyalty to Hitler’s Germany. Not long after the fall of Sicily, the Italian government decided to throw in its lot with the Allies.

The Invasion of Italy. In September 1943 the Allies began their invasion of Italy when American troops landed at Salerno. Prior to that General Montgomery’s Eighth British Army had begun its invasion of the toe of the Italian boot just across from Sicily. General Marshall and the American staff in Washington had been hesitant to invest large forces in Italy. They believed that an invasion of northwestern Europe, which eventually took place on D-Day, June 6, 1944, was the quickest route to the defeat of Germany. But Hitler had sent substantial forces into Italy, and in order to keep them from reinforcing the western defenses, the Allied staffs felt it was necessary for the Italian operation to move forward to keep that portion of the German Army tied down.

Field Marshal Kesselring, the German commander in Italy, made excellent use of the rugged terrain of Italy, which favored the defense. The combination of mountains, rivers, and deep valleys made it very difficult for the Allies to advance against the well-placed defenders. The American Fifth Army under the command of General Mark Clark began advancing up the coast after the initially successful landings, but they were soon met by strong German counterattacks. As allied reinforcements continued to arrive, however, the Germans were obliged to withdraw to the north. In October the American Fifth and British Eighth Armies established a line across the Italian peninsula and began to advance on a united front.

The winter of 1943–44 proved a difficult one for the Allied forces as a combination of terrain and weather made the advance extremely slow and painful. In January 1944 the Allies executed a second landing at Anzio designed to disrupt the German forces from the rear. Impeding the Allied advance was the great fortress monastery of Cassino, which lay on the path to Rome. Throughout early 1944 the Allied advance in Italy was slow, and at times the entire operation seemed in jeopardy. During the spring, however, Allied commanders used a combination of maneuver and close air support, eventually captured Monte Cassino, and fought their way into Rome. They entered the Italian capital on June 4, 1944.

The winter of 1943–44 proved a difficult one for the Allied forces as a combination of terrain and weather made the advance extremely slow and painful. In January 1944 the Allies executed a second landing at Anzio designed to disrupt the German forces from the rear. Impeding the Allied advance was the great fortress monastery of Cassino, which lay on the path to Rome. Throughout early 1944 the Allied advance in Italy was slow, and at times the entire operation seemed in jeopardy. During the spring, however, Allied commanders used a combination of maneuver and close air support, eventually captured Monte Cassino, and fought their way into Rome. They entered the Italian capital on June 4, 1944.

The German Army under Kesselring continued to retreat northward and withdrew to a position 150 miles north of Rome. The Allies, however, were unable to pursue closely because Operation Overlord (D-Day) and Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France which was to serve as a distraction for the main D-Day operations, were about to get underway, and Allied troops were withdrawn from Italy to participate in those landings.

Operation Overlord: The Invasion of France, 1944

Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, commonly referred to as D-Day, was the largest amphibious operation ever conducted and perhaps the most complicated military maneuver ever undertaken. The mere numbers are staggering:

- The Allies landed 156,000 troops in one day, including 73,000 Americans, on the beaches, and dropped 15,000 airborne troops behind enemy lines.

- Operation Neptune, the naval component of D-Day, involved 7,000 vessels, including 4,000 transport ships, 1,200 warships, countless small landing craft, and about 200,000 personnel.

- Air support for the invasion involved 11,590 aircraft.

- Airborne (parachute and glider) drops involved 2,395 aircraft and 867 gliders of the RAF and The United States Army air Corps.

- Hundreds of thousands more military and civilian personnel supported the operation throughout the Allied nations, including underground resistance workers in France.

- By D-Day + 5, June 11, the Allies had landed 326,547 troops, 54,186 vehicles, and 104,428 tons of supplies.

Planning for the Normandy operation had been going on for months. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was in overall command of the Allied forces. British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery was in command of the Allied land forces. General Omar N. Bradley commanded the American forces. General George S. Patton’s Third Army was held out of the initial landings, partly as a scheme to confuse German intelligence, and partly because of his behavior problems, which irritated General Eisenhower. (Even following the incident of his slapping a soldier he accused of cowardice in an earlier campaign, General Patton had made a troublesome public speech about postwar issues that had reverberated all the way back to Congress, even after General Eisenhower had cautioned the outspoken general about such things.)

Planning for the Normandy operation had been going on for months. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was in overall command of the Allied forces. British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery was in command of the Allied land forces. General Omar N. Bradley commanded the American forces. General George S. Patton’s Third Army was held out of the initial landings, partly as a scheme to confuse German intelligence, and partly because of his behavior problems, which irritated General Eisenhower. (Even following the incident of his slapping a soldier he accused of cowardice in an earlier campaign, General Patton had made a troublesome public speech about postwar issues that had reverberated all the way back to Congress, even after General Eisenhower had cautioned the outspoken general about such things.)

During the buildup for D-Day, an entire phony army supposedly commanded by Patton was created, with hundreds of trucks tanks and aircraft, all of which were dummy balloon creations. Phony but realistic sounding radio traffic was generated, and Hitler was convinced that the invasion of Europe would not take place without Patton, whom he considered to be the most dangerous American general. He was sure that the invasion would come at the Calais instead of on the beaches in Normandy. The real Third Army landed several weeks later and assisted in the Allied breakout from the Normandy beachhead. (See the film Patton for more detail on his role in the battle against Germany.)

German commanders in France were Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. Prior to the invasion the Allies had engaged in extensive counterintelligence operations, including the creation of the phony army mentioned above. German intelligence was never quite sure exactly where the landings were to take place, and the foul weather preceding and following D-Day contributed to their suspicion that the Normandy landings were not the real thing. The German staff in Berlin was so uncertain about the scope of the Normandy landings that they failed to notify Hitler until hours after the invasion had begun. (By that time, Hitler's behavior had become so erratic that the generals were loath to confront him with anything that might be bad news.)

The actual operation began just after midnight on June 6, 1944, when British and American airborne forces landed behind the German defenses known as the Atlantic Wall on the Cherbourg Peninsula. At daybreak the U.S. First Army and British Second Army as well as Canadian, Polish, and French troops stormed the beaches of Normandy. The landings for the most part went more smoothly than had been hoped, but the V Corps of the First U.S. Army on Omaha Beach met fierce resistance. Initial casualties on the beaches were horrific, with some units experiencing almost 100% losses and thousands of men died without ever reaching the beach or firing a shot. Despite that resistance they managed to get a foothold about one mile deep by the end of the first day. (Steven Spielberg’s 1998 film Saving Private Ryan graphically depicts the action on Omaha Beach during the initial landing.) American casualties on Omaha Beach were about 3,000 killed, wounded or missing.

When General Eisenhower received the first reports of the landings, his main concern was linking the American units that had landed on Omaha and Utah beaches and connecting them with the 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions, whose drops had been widely scattered. Eisenhower visited with the British and American ground commanders regularly and established a headquarters in Normandy early in July. The successful Allied counterintelligence operations had led the Germans to believe that the Normandy invasion was not the main assault, with the result that an entire German army was held in reserve for several weeks, significantly aiding Allied efforts.

When General Eisenhower received the first reports of the landings, his main concern was linking the American units that had landed on Omaha and Utah beaches and connecting them with the 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions, whose drops had been widely scattered. Eisenhower visited with the British and American ground commanders regularly and established a headquarters in Normandy early in July. The successful Allied counterintelligence operations had led the Germans to believe that the Normandy invasion was not the main assault, with the result that an entire German army was held in reserve for several weeks, significantly aiding Allied efforts.

While British forces tied up the main German resistance in the Caen area throughout June and early July, American forces consolidated their hold on the Cherbourg Peninsula. The port of Cherbourg was needed for the unloading of supplies. In July the American forces were ready to attempt a breakout from the positions they had gained since D-Day. General Patton’s Third Army had been moved into France, and the American First and Third Armies were reorganized for tactical advantage. By late July the Allies were well on the move toward Paris.

As the American armored units, which consumed huge quantities of ammunition and fuel, continued to drive the Germans back, keeping the advanced combat units supplied remained a huge challenge. Special motor transport units were established with trucks of fuel and supplies being driven virtually nonstop by teams of drivers who were organized into a unit known as the “Red Ball Express.” The fact that American units were filled with bright young men with varying skills was a positive factor in solving various logistical and technical problems.

One example of American ingenuity came to the fore when it was discovered that tanks had difficulty traversing the irrigated agricultural areas because of lack of traction. A young engineer in the ranks suggested that much of the defensive material on the beaches that had been dismantled by engineers could be used to solve the problem by welding onto the sides of the tanks strips of metal that would dig into the turf and give the tanks better traction.

Also apparent during the massive offensive was the force of matériel supplied by American factories. Countless tons of ammunition, spare parts, vehicles, communications equipment, weapons, and every other conceivable item needed for soldiers in battle arrived in huge quantities. An apocryphal story told of an incident during a German counterattack that had briefly captured an American position. A German intelligence officer inspecting captured material noticed a package containing a birthday cake that had been mailed to a soldier from his family in Boston. Furious at the implication, he demanded to know of his commander how Germany could hope to win a war when they were running short of fuel while the Americans could manage to get a fresh birthday cake to the front lines in a matter of days.

Tensions existed from time to time between General Montgomery and the American commanders, and General Eisenhower often found himself acting as referee in what can be described as politico-military squabbles. Not only did he have to deal with strong-willed, hotheaded generals such as George Patton, he also had to deal with the French forces under General Charles de Gaulle.

The Liberation of Paris. By August allied forces had penetrated well into France. Eisenhower's plan was to bypass Paris for the time being, but Charles de Gaulle would have none of it. He was determined that the French capital be liberated and that he would be a part of it. The battle for Paris lasted a week, and it was finally liberated on August 25, 1944. The attack was preceded by the actions of the French resistance, who did everything they could to disrupt German communications. Although he had been commanded by Hitler to destroy the major monuments in Paris and set the city on fire, German General Cholitz refused to follow the order. The French Second Armored Division entered the city and Charles de Gaulle took head of the provisional government of the French Republic.

The Liberation of Paris. By August allied forces had penetrated well into France. Eisenhower's plan was to bypass Paris for the time being, but Charles de Gaulle would have none of it. He was determined that the French capital be liberated and that he would be a part of it. The battle for Paris lasted a week, and it was finally liberated on August 25, 1944. The attack was preceded by the actions of the French resistance, who did everything they could to disrupt German communications. Although he had been commanded by Hitler to destroy the major monuments in Paris and set the city on fire, German General Cholitz refused to follow the order. The French Second Armored Division entered the city and Charles de Gaulle took head of the provisional government of the French Republic.

The rapid advance of the American and British forces in August and September 1944 led to critical shortages of supplies, especially gasoline. Tanks, armored vehicles, and trucks were consuming millions of gallons, but transporting it strained the resources of the quartermaster troops to their limit. As Allied staffs studied plans for the advance toward the Rhine, tensions arose again as different commanders put forth plausible plans for the advance. There were not enough supplies to go around, and General Eisenhower was faced with the problem of deciding where to allocate resources. He was in a no-win situation—no matter who received the lion’s share of troop replacements, ammunition, and gasoline, field commanders like Patton and Montgomery were sure to raise objections and complain about alleged favoritism.

Operation Market Garden. Heading nto the month of October various strategies were considered to defeat the Germans, and major units underwent frequent reorganizations to take advantage of the abilities of the different divisions. One of those operations, Market Garden, proposed by Field Marshal Montgomery, called for an attack through Belgium into northern Germany and across the Rhine. The objective was to capture a series of bridges across the river enabling the Allied forces to advance toward Berlin. The attack involved a combined Allied Airborne Army and a Corps of the British Second Army. The attack was launched in September 1944. The main part of the battle took place at Arnhem, where Allied forces failed to dislodge the Germans defending the bridge. The allies were unable to secure a bridgehead across the river, and the attack was a failure that cost a large number of Allied casualties. As winter approached, the Allies settled down to prepare for the final assault on Germany itself. The crossing of the Rhine would not take place until March 1945. (A film about the oeration, A Bridge Too Far, tells the story.)

The Battle of the Bulge, 1944–45

Disappointed by his generals’ inability to defeat the Allied landings in Normandy or to retard their advance across France and through Belgium and the Netherlands, Hitler ordered a massive counterattack against the Americans and British in December 1944. German planners did their best to conceal the impending attack and to confuse Allied defenders once the fighting had begun. They used English-speaking German soldiers dressed in American uniforms and other forms of deception to divert Allied traffic and sow confusion.

The Americans and British had advanced rapidly and had been slowed down mostly by lack of gasoline and other supplies, as opposed to German resistance. Thus they had perhaps grown complacent, believing that the German army was ready to fold. Through a combination of faulty intelligence and bad weather, which hampered the operation of reconnaissance aircraft, the Germans were able to strike the Americans completely by surprise.

What became known as the Battle of the Bulge began on December 16, 1944, as German divisions attacked on a sixty-mile front. Because American divisions had suffered substantial losses and were therefore manned with many inexperienced troops, the Germans were able to advance rapidly. Many small units were cut off and surrounded, though they continued to fight courageously.

What became known as the Battle of the Bulge began on December 16, 1944, as German divisions attacked on a sixty-mile front. Because American divisions had suffered substantial losses and were therefore manned with many inexperienced troops, the Germans were able to advance rapidly. Many small units were cut off and surrounded, though they continued to fight courageously.

General Eisenhower rushed an airborne division into the Belgian city of Bastogne, which had been surrounded. Closing in on the Americans, the Germans sent an envoy to the airborne commander, General Anthony C. McAuliffe. As the German officer made the offer known, General McAuliffe uttered his famous one word response: “Nuts!” When the German negotiator asked the American major for a clarification, not fully understanding what the word “nuts” meant, the American offered a more blunt translation: “Go to hell!”

As the weather cleared, the Germans were hampered by air attacks and their own shortage of supplies. At one point German tanks ran out of fuel within a few hundred yards of a fuel dump containing thousands of gallons of gasoline. The difficult engagement cost the Americans heavily, and they suffered approximately 77,000 casualties. The result of all the fighting was a large bulge in the American lines, from which the battle took its name.

The German counteroffensive had a sobering effect on the American unit commanders, who now realized that the Germans were by no means through fighting. A rapid shift in the attacking direction of the Third Army relieved Bastogne, and the American advance toward the Rhine resumed. By the end of January all the lost territory had been recaptured and additional German counterattacks had also been blunted. The advance on the Rhine resumed.

Germany Conquered. On March 7, 1945, members of the Ninth U.S. Armored Division discovered that the Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine River at Remagen and had not been destroyed by the Germans, and thus a foothold across the river suddenly became available. Americans fought their way across the bridge under intense fire, and following counterattacks the Germans attempted to destroy it. Although the bridge eventually collapsed from the demolitions placed on it, pontoon bridges were set up alongside the railroad bridge, and within a week elements of several army divisions had crossed to the east bank and were fighting on German soil. The end was in sight. By April 20 the Soviet Army was on the outskirts of Berlin, and American units were advancing on the city.

On April 30 Hitler committed suicide, and Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, which became known as V-E Day. General Esienhower accepted the German surrender from General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Operations Staff in the German High Command. Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel surrendered to the Soviets in Berlin. Preparations for the post war division of Germany had been made at Yalta by Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin. For all practical purposes, Germany ceased to exist as an independent nation. Many of its cities were in ruins, and it would take years, even decades, for Germany to return to something approaching its prewar existence.

Casualties & Costs. The exact number of dead and wounded in World War II can only be approximated. It is likely that the European war cost between 40 and 50 million lives. The physical destruction of toewwns and cities took years to repair, and the signs linger to this day. Millions more died in China and Japan. In the months and years following the war millions of Europeans separated from their homes struggled to put their lives back together. For many, the worst suffering of the war came after the fighting had ceased, as food, shelter and medical aid were often in short supply. Occupying forces did what they could to aid the conquered peoples, but it took years for full recovery to be achieved. And, of course, the millions of deceased persons remained gone.

While the war against Germany was being fought on land, on sea, and in the air, another struggle was going on inside the Third Reich, the grisly details of which did not emerge faithful until after the war was over. Indications of what was coming or apparent, well before the war began. In Mein Kampf Hitler made it clear that he considered the Jewish people to be lesser beings, not entitled to the rights of other citizens. Anti-Semitism had been around for centuries, but never before had the atrocities carried out by the SS been so widespread and brutal.

The first signs were discriminatory acts carried out upon the Jewish population, depriving him of certain rights and privileges. Then in November, 1938, on what became known as Kristallnach—the "night of broken glass." Nazi leaders engineered a widespread assault on Jewish homes, hospitals, synagogues and businesses, smashing windows, destroying the contents of buildings and knocking down walls. Hundreds of Jews were murdered, and thousands were incarcerated and sent to concentration camps. There were no legal proceedings or trials involved; once a person was identified as a Jew, he or she was subject to arrest with no attendant judicial process. Nazi propaganda tried to make the case that the violence was a spontaneous uprising by the people in protest against Jewish influences. He action which spread throughout Germany, Austria and occupied Czechoslovakia was clearly engineered by the SA storm troopers and the SS.

The first signs were discriminatory acts carried out upon the Jewish population, depriving him of certain rights and privileges. Then in November, 1938, on what became known as Kristallnach—the "night of broken glass." Nazi leaders engineered a widespread assault on Jewish homes, hospitals, synagogues and businesses, smashing windows, destroying the contents of buildings and knocking down walls. Hundreds of Jews were murdered, and thousands were incarcerated and sent to concentration camps. There were no legal proceedings or trials involved; once a person was identified as a Jew, he or she was subject to arrest with no attendant judicial process. Nazi propaganda tried to make the case that the violence was a spontaneous uprising by the people in protest against Jewish influences. He action which spread throughout Germany, Austria and occupied Czechoslovakia was clearly engineered by the SA storm troopers and the SS.

The actions outlined above were just the beginning. In addition to the tens of millions of people both military and civilian who died in the war, millions more were put to death in Nazi concentration camps in Germany and Poland. The majority of the deaths casualties were directly attributable to the war itself, but millions more were caused by an evil even greater than war: the deliberate murder of human beings as a matter of national policy. Although he did not spell out the details of his plaanfor the Jews, Hitler proposed a radical solution to what he called the “Jewish problem” in Mein Kampf. Although his book was widely sold, it was not widely read, and in any case even those who read it would have had difficulty foreseeing what actually occurred.

The Nazi government had started creating concentration camps as soon as it came to power in 1933. By 1939, six large camps existed, including Dachau (1933), Sachsenhausen (1936) and Buchenwald (1937). The most notorious of the concentration camps, Auschwitz, was created after the Germans invaded Poland in 1939. Those who were fit for work were used as forced labor from the beginning of the war. Those who were sick or infirm or otherwise incapable of being productive were summarily executed. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Hitler’s generals and officials expected a rapid end to the war and gave little thought to the ultimate disposition of the Jewish and other prisoners in the concentration camps. Early in 1942, however, with the United States in the war and German armies bogged down in Russia, a conference was called at Hitler’s direction to establish a “final solution” for the Jewish problem.

The Head of the Gestapo, Reinhard Heydrich, issued an invitation to representatives of all German major government departments to a conference at Wannsee in January, 1942. Aming those in attendance were representatives of the departments of Justice and the Interior. The recording secretary was Adolf Eichmann. Heydrich ran the meeting with ruthless efficiency and issued blunt instructions to all attendees to cooperate in the extermination of the entire Jewish population of Germany and Eastern Europe. By 1942 hundreds of large and small concentration camps existed in every German occupied territory.

Although killings were carried out by shooting early in the war, the large number of prisoners to be killed required more efficient methods. Poison gas and exhaust fumes from diesel trucks were the methods most commonly used. Bodies were disposed of in mass graves or burned in crematoria. Many Jews and other prisoners died on their way to concentration camps as they were locked in rail cars without food or water, often for days or even weeks at a time. As the German army advanced in the East, special SS units were deployed to round up Jews and other “undesirables” and execute them on the spot. Prisoners were ordered to dig mass graves in the earth and were then shot. Bulldozers were used to push bodies into the graves and cover them with dirt.

Although killings were carried out by shooting early in the war, the large number of prisoners to be killed required more efficient methods. Poison gas and exhaust fumes from diesel trucks were the methods most commonly used. Bodies were disposed of in mass graves or burned in crematoria. Many Jews and other prisoners died on their way to concentration camps as they were locked in rail cars without food or water, often for days or even weeks at a time. As the German army advanced in the East, special SS units were deployed to round up Jews and other “undesirables” and execute them on the spot. Prisoners were ordered to dig mass graves in the earth and were then shot. Bulldozers were used to push bodies into the graves and cover them with dirt.

The literature on the Holocaust is vast. The total number of Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, communists, people with mental and physical handicaps, and others will never be reckoned, but the total was at least 10 million, of whom 6 million were Jews. The Holocaust was deliberate, state-sponsored genocide, one of the greatest humanitarian tragedies and most horrific acts in the history of the world. Despite massive evidence in the form of documents, photographs, films, and the testimony of survivors, there are still those who doubt that the holocaust occurred, or who claim that the number of people killed has been hugely exaggerated. Institutions like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC attempt to tell the real story of what happened, but there are still those who doubt.

At the rear entrance to the Museum is a plaque with a quote from General Eisenhower, who visited the concentration camps after the war was over. He told General Marshall:

“The things I saw beggar description….The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty, and bestiality were…overpowering….I made the visit deliberately in order to be in a position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to ‘propaganda.’”

General Eisenhower was wise enough to foresee what actually came about. The above quote is on a plaque in the Plaza on the 15th street side of the museum, shown in the photo above left.

| World War II Home | Updated April 3, 2020 |