|

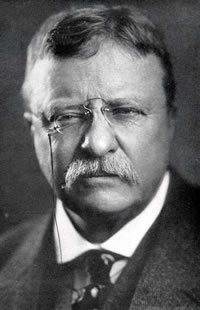

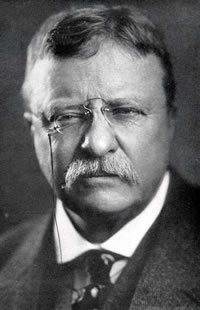

The “Roosevelt

Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine

When

the Venezuelan government stopped paying back its debts to European bankers

in 1902, “naval forces of Britain, Italy, and Germany erected a blockade

along that country's coast.” As rumors spread that Germany was going to

establish a permanent base in the region, President Theodore Roosevelt grew

alarmed and warned the Germans to withdraw. This incident prompted Roosevelt

to update the “Monroe Doctrine” with the new corollary that he announced

in a 1904 message to Congress. Roosevelt, like his later rival, Woodrow Wilson, sometimes had difficulty distinguishing between legitimate influence and unwarranted meddling in the affairs of others. No doubt the intentions of both presidents were good, but that was not always the perception in nations who felt the heavy hand of American interference. Not until the Good Neighbor policy was begun under Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt did relations with our Latin neighbors improve substantially.

It is not true

that the United States feels any land hunger or entertains any projects as regards

the other nations of the Western Hemisphere save such as are for their welfare.

All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly,

and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon

our hearty friendship. If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable

efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and

pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic

wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties

of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention

by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the

United States to the Monroe Doctrine may lead the United States, however reluctantly,

in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international

police power. If every country washed by the Caribbean Sea would show the progress

in stable and just civilization which with the aid of the Platt amendment Cuba

has shown since our troops left the island, and which so many of the republics

in both Americas are constantly and brilliantly showing, all question of interference

by this Nation with their affairs would be at an end. Our interests and those

of our southern neighbors are in reality identical. They have great natural

riches, and if within their borders the reign of law and justice obtains, prosperity

is sure to come to them. While they thus obey the primary laws of civilized

society they may rest assured that they will be treated by us in a spirit of

cordial and helpful sympathy. We would interfere with them only in the last

resort, and then only if it became evident that their inability or unwillingness

to do justice at home and abroad had violated the rights of the United States

or had invited foreign aggression to the detriment of the entire body of American

nations. It is a mere truism to say that every nation, whether in America or

anywhere else, which desires to maintain its freedom, its independence, must

ultimately realize that the right of such independence can not be separated

from the responsibility of making good use of it. It is not true

that the United States feels any land hunger or entertains any projects as regards

the other nations of the Western Hemisphere save such as are for their welfare.

All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly,

and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon

our hearty friendship. If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable

efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and

pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic

wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties

of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention

by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the

United States to the Monroe Doctrine may lead the United States, however reluctantly,

in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international

police power. If every country washed by the Caribbean Sea would show the progress

in stable and just civilization which with the aid of the Platt amendment Cuba

has shown since our troops left the island, and which so many of the republics

in both Americas are constantly and brilliantly showing, all question of interference

by this Nation with their affairs would be at an end. Our interests and those

of our southern neighbors are in reality identical. They have great natural

riches, and if within their borders the reign of law and justice obtains, prosperity

is sure to come to them. While they thus obey the primary laws of civilized

society they may rest assured that they will be treated by us in a spirit of

cordial and helpful sympathy. We would interfere with them only in the last

resort, and then only if it became evident that their inability or unwillingness

to do justice at home and abroad had violated the rights of the United States

or had invited foreign aggression to the detriment of the entire body of American

nations. It is a mere truism to say that every nation, whether in America or

anywhere else, which desires to maintain its freedom, its independence, must

ultimately realize that the right of such independence can not be separated

from the responsibility of making good use of it.

In asserting the

Monroe Doctrine, in taking such steps as we have taken in regard to Cuba, Venezuela,

and Panama, and in endeavoring to circumscribe the theater of war in the Far

East, and to secure the open door in China, we have acted in our own interest

as well as in the interest of humanity at large. There are, however, cases in

which, while our own interests are not greatly involved, strong appeal is made

to our sympathies... In extreme cases action may be justifiable and proper.

What form the action shall take must depend upon the circumstances of the case;

that is, upon the degree of the atrocity and upon our power to remedy it.

|

It is not true

that the United States feels any land hunger or entertains any projects as regards

the other nations of the Western Hemisphere save such as are for their welfare.

All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly,

and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon

our hearty friendship. If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable

efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and

pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic

wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties

of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention

by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the

United States to the Monroe Doctrine may lead the United States, however reluctantly,

in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international

police power. If every country washed by the Caribbean Sea would show the progress

in stable and just civilization which with the aid of the Platt amendment Cuba

has shown since our troops left the island, and which so many of the republics

in both Americas are constantly and brilliantly showing, all question of interference

by this Nation with their affairs would be at an end. Our interests and those

of our southern neighbors are in reality identical. They have great natural

riches, and if within their borders the reign of law and justice obtains, prosperity

is sure to come to them. While they thus obey the primary laws of civilized

society they may rest assured that they will be treated by us in a spirit of

cordial and helpful sympathy. We would interfere with them only in the last

resort, and then only if it became evident that their inability or unwillingness

to do justice at home and abroad had violated the rights of the United States

or had invited foreign aggression to the detriment of the entire body of American

nations. It is a mere truism to say that every nation, whether in America or

anywhere else, which desires to maintain its freedom, its independence, must

ultimately realize that the right of such independence can not be separated

from the responsibility of making good use of it.

It is not true

that the United States feels any land hunger or entertains any projects as regards

the other nations of the Western Hemisphere save such as are for their welfare.

All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly,

and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon

our hearty friendship. If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable

efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and

pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic

wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties

of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention

by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the

United States to the Monroe Doctrine may lead the United States, however reluctantly,

in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international

police power. If every country washed by the Caribbean Sea would show the progress

in stable and just civilization which with the aid of the Platt amendment Cuba

has shown since our troops left the island, and which so many of the republics

in both Americas are constantly and brilliantly showing, all question of interference

by this Nation with their affairs would be at an end. Our interests and those

of our southern neighbors are in reality identical. They have great natural

riches, and if within their borders the reign of law and justice obtains, prosperity

is sure to come to them. While they thus obey the primary laws of civilized

society they may rest assured that they will be treated by us in a spirit of

cordial and helpful sympathy. We would interfere with them only in the last

resort, and then only if it became evident that their inability or unwillingness

to do justice at home and abroad had violated the rights of the United States

or had invited foreign aggression to the detriment of the entire body of American

nations. It is a mere truism to say that every nation, whether in America or

anywhere else, which desires to maintain its freedom, its independence, must

ultimately realize that the right of such independence can not be separated

from the responsibility of making good use of it.