Post-World War II Domestic Part 2

The Johnson and Nixon Years

The Johnson Years: America in Turmoil

Lyndon Baines Johnson was one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in American political history. He was a man of extraordinary talents, appetites and ambition. He first came Washington from Texas in 1931 as secretary to a Texas congressman, where he caught the attention of Franklin Roosevelt and was appointed as Director of the Texas National Youth Administration. He was elected to a full term in the House of Representatives in 1938 and served there until 1948, when he was elected to the United States Senate.

In 1951 Johnson was elected majority whip of the Democratic Party in the Senate, and in 1955 he became the Senate Majority Leader, a position he held until being elected vice president under John F. Kennedy in 1960. During the 1960 Democratic convention once Senator Kennedy was assured of the nomination, the question of his running mate arose. Although the negotiations were carried out in private, evidence exists that John Kennedy did not really want Johnson as his vice president, but since Johnson, as majority leader of the Senate, was the most powerful man in Washington in 1960, Kennedy and his aides felt that Johnson should be offered the job. They also counted on Johnson to deliver the electoral votes of his native Texas as well as other Southern states. The Kennedy team was apparently shocked when Johnson decided to accept the position. Although doubts were later raised about the process of selecting the vice presidential candidate, Johnson was placed on the Democratic Party ticket and was elected alongside Senator Kennedy.

The vice presidency of the United States has been described in less than glowing terms by more than one occupant of the office, and there is no question that Lyndon Johnson was frustrated over his lack of meaningful responsibilities while in that position. President Kennedy made him overseer of the American space program, but that did not really satisfy Johnson's longing to be in the center of political action in Washington. He was assigned several diplomatic missions, which gave him fresh insight into international affairs. Kennedy's closest advisers, however, including his brother Attorney General Robert Kennedy, did not care for Johnson's brusque, heavy-handed style, and openly showed their dislike for the vice president. Johnson's term in that office was largely a time of frustration for a man who had been so powerful in the Senate, as his attempts to increase his influence in the White House were rebuffed.

The Kennedy Assassination. Because of Johnson's influence in Texas, the president wanted Johnson to accompany him on his trip to the state in 1963. The vice president was therefore with President Kennedy on that fateful trip. After the shooting when it became clear that Kennedy would not survive, the vice president was immediately rushed from Dallas’s Parkland Hospital to Air Force One as a precautionary measure. As soon as they were aboard the aircraft Johnson was sworn in as president while First Lady  Jacqueline Kennedy, now a widow, stood by in her bloodied pink suit. (See image at left.)

Jacqueline Kennedy, now a widow, stood by in her bloodied pink suit. (See image at left.)

The transition from the Kennedy to the Johnson administration was understandably wrenching, first of all because Kennedy's cabinet and staff were in a state of shock following the sudden death of their leader. In addition, John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson were about as far apart as two politicians of the same party could get in style, background and personality. Kennedy, the wealthy scion of an old Boston political family and Harvard graduate, epitomized everything glamorous and attractive about Washington politics. Jacqueline Kennedy, a sophisticated and charming First Lady who had attracted considerable attention from the press, conducted herself with enormous dignity during the ceremonies following her husband's death. Pictures of her standing side-by-side with her two young children, her son John being too young to comprehend what was happening, deeply touched the American people.

Lyndon Johnson, by contrast, had come from humble beginnings, He attended Southwest Texas State Teachers College and, after teaching for a year, worked his way up through the political ranks by his own means. Whereas the Kennedys suggested candlelit tables with fine glassware and china, Lyndon Johnson and his family conveyed the image of a rousing Texas barbecue. Johnson moved slowly and carefully during the weeks and months following Kennedy’s death, looking forward to the election of 1964 as he renewed contacts with political colleagues in Congress and elsewhere. As president, with the full apparatus of the White House at his disposal, he commanded attention and demanded loyalty.

Johnson’s forte was not foreign affairs, but the Cold War was a continuing reality, and the situation in Vietnam following the assassination of Premier Diem was murky at best; he could not afford to ignore the realities of international events. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which had been passed in August, 1964, gave the president wide authority to prosecute the war in Vietnam as he saw fit. Johnson, however, preferred to focus on his domestic agenda and did not take any strong action in Vietnam until after he was reelected. Johnson later told biographers that his goal had been to dance with the lady he came to call the “Great Society,” but instead he was distracted by what he called that “bitch goddess of Vietnam.” Although his achievements in pursuit of his goals for domestic improvements were stunning, in the end his legacy was determined largely by the Vietnam War. (See separate section on Vietnam.)

As president, Johnson planned an all-out assault on what he saw as America's social skills: racism, poverty, lack of opportunity for the poor, and a host of other issues first addressed by Franklin Roosevelt during the New Deal. Not long after the assassination the president addressed Congress and said that the best way to honor the memory of John Kennedy was the “earliest possible passage of the Civil Rights Bill for which he fought so long.” The goal of addressing civil rights issues was high on President Johnson’s agenda. Kennedy had initiated a civil rights program, but it was still far from completion upon his death. As a Southerner Johnson was in a strong position to push civil rights legislation.

Though it took all his powers of persuasion, Johnson's achievements in civil rights were of major significance. Therefore his first task once he returned to Washington following the assassination was gaining passage of the civil rights bill that had been introduced by President Kennedy in 1963. Johnson spent most of his time early in 1964 working to get Congress to pass the bill. The House passed the bill by a comfortable margin, but it faced an uphill fight in the Senate. Johnson was aware that Southern Senators would lead a filibuster against the bill, and a vote of two thirds of the Senate was required to end it. Johnson kept a list of where every member of the Senate stood on the issue, and pulled out all the stops in an effort to persuade his former Senate colleagues to come around. The filibuster lasted three months, the longest one in Senate history, but eventually the bill passed. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law on July 2.

The 1964 Election. For all his power and political savvy, Johnson was nervous about the coming election of 1964. Although there was a likelihood that he would benefit from the shock of Kennedy's assassination with a "sympathy vote," he was also afraid that Kennedy's supporters might desert him because he failed to name Robert Kennedy as his preference for vice president. Instead he named Senator Hubert Humphrey as his running mate and worked hard in the  campaign. The Republican Party, sharply divided between his conservative and liberal-moderate wings, chose conservative Senator Barry Goldwater over more moderate Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York. Some of Goldwater's positions were seen as extreme, and that fact along with the so-called sympathy vote led to a huge landslide for Johnson. With a margin of 61.1% of the popular vote, the largest margin in modern American history, along with 486 electoral votes, Johnson won in a landslide. Having comfortably won the election, Johnson retired to his ranch in Texas until the first of the year to plan his legislative strategy. He took no action regarding the Vietnam war until he returned to Washington.

campaign. The Republican Party, sharply divided between his conservative and liberal-moderate wings, chose conservative Senator Barry Goldwater over more moderate Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York. Some of Goldwater's positions were seen as extreme, and that fact along with the so-called sympathy vote led to a huge landslide for Johnson. With a margin of 61.1% of the popular vote, the largest margin in modern American history, along with 486 electoral votes, Johnson won in a landslide. Having comfortably won the election, Johnson retired to his ranch in Texas until the first of the year to plan his legislative strategy. He took no action regarding the Vietnam war until he returned to Washington.

Lyndon Johnson was one of the most powerful politicians in the nation's history. Now president in his own right, he brought all his skills to bear on the issues in which he believed. He could be cajoling, pleading, bargaining, threatening, or promising, sometimes, it seemed, all in the course of the same conversation. He was famous for what was known as the “Johnson Treatment.” He was a man not to be crossed with impunity. Although he was unfailingly gracious to Jacqueline Kennedy following JFK's assassination, the “Kennedy crowd,”or “Irish Mafia,” often left him feeling frustrated and angry. While he kept major Kennedy advisors such as Defense Secretary McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk, he often clashed with JFK's brother Robert, especially when the former attorney general began to challenge his Vietnam policy.

When issues were raised regarding possible conspiracies involved in president Kennedy's assassination, President Johnson quickly created an investigative body added by Chief Justice Earl Warren. The Warren commission studied the evidence and concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone in the assassination. Conspiracy theories persisted for years, however.

As discussed in detail in the Civil Rights section, two more major bills were passed during Johnson’s second term: the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Including the Civil Rights Act of1964, the three acts reflect Lyndon Johnson’s sincere commitment to racial equality. As a Texan, he had seen racial discrimination up close and detested its effects on blacks and Mexicans. As a Congressman and Senator, he had worked hard to see that minorities were fairly treated under federal economic policies. His achievements in this area provide a stark contrast to his unfortunate policy in Vietnam.

Among Lyndon Johnson's additional goals related to the three acts above was what he called his War on Poverty, which took a variety of legislative forms. Johnson's achievements toward that end included bills to establish the Medicare and Medicaid programs; the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964; creation of the Job Corps, a sort of domestic Peace Corps; the Elementary and Secondary Education Act; and the Head Start program. Johnson also sponsored legislation that revised immigration policies, toughened anti-crime systems, and sought to improve public housing and clean up urban slums and the environment at large. Johnson used every aspect of his powers of persuasion, including legislative arm-twisting devices, to get his programs through Congress.

The assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert F Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. raised concerns about the lack of effective gun control in the country. Several attempts had been made to tighten gun laws in the United States, but they met with fierce opposition. The Gun Control Act of 1968 was finally passed as a result of the latter assassinations and signed by President Johnson in October, 1968. The purpose of the act was to regulate interstate commerce in firearms by prohibiting that traffic except among licensed manufacturers and gun dealers. Part of the motivation came from the fact that President John Kennedy was shot and killed with a rifle that was purchased by mail order from an ad in a magazine. Following the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan and the injury to Press Secretary James Brady, the act was strengthened in 1993.

President Johnson also made two important appointments that further advanced his civil rights agenda. Thurgood Marshall was appointed as the first African-American justice on the Supreme Court, and Robert Weaver, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, was the first African-American cabinet secretary in American history. Although many of Johnson's programs failed to fully meet their objectives, it was the greatest reform movement since the early days of FDR’s New Deal. Lyndon Johnson presided over much of the “the sixties,” however, and the times were indeed a-changing.

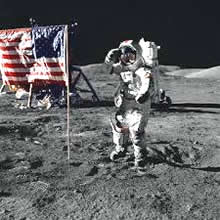

America Goes to the Moon. Having launched the country on a quest to put an American on the moon by 1970, President Kennedy committed the nation to exploration of the heavens. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration mobilized the American scientific and engineering communities in a remarkable  program to realize Kennedy’s vision. The seven Mercury astronauts made flights in the early 1960s, and then the Gemini and Apollo programs began to prepare for an eventual lunar landing. With the assistance of former German V-weapon rocket scientists and an aviation industry with much talent, the Apollo program moved forward smartly as NASA administrators kept a close eye on Soviet developments. In July 1969 the U.S. space program reached Kennedy’s goal: Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon. With millions listening, Neil Armstrong announced, "That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind."

program to realize Kennedy’s vision. The seven Mercury astronauts made flights in the early 1960s, and then the Gemini and Apollo programs began to prepare for an eventual lunar landing. With the assistance of former German V-weapon rocket scientists and an aviation industry with much talent, the Apollo program moved forward smartly as NASA administrators kept a close eye on Soviet developments. In July 1969 the U.S. space program reached Kennedy’s goal: Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon. With millions listening, Neil Armstrong announced, "That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind."

The Apollo achievement was remarkable in that virtually every piece of equipment used for the flight had to be created from scratch. The challenges were large; three astronauts died in a fire early in the program, and three more nearly perished when the Apollo 13 spacecraft was damaged in an internal explosion. NASA eventually oversaw six landings on the moon, the last of which took place on December 11, 1972. Since then all space flights have been limited to low orbits. The Space Shuttle program, which followed Apollo, accomplished much but was plagued by accidents. The Challenger shuttle was destroyed during a launch in 1986, and the Columbia was destroyed during re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere in 2003.

NASA eventually oversaw six landings on the moon, the last one on December 11, 1972. Since then all space flights have been limited to low orbits. The Space Shuttle program, which followed Apollo, accomplished much but was plagued by accidents, as the Challenger shuttle was destroyed during a launch in 1986, and the Columbia was destroyed during re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere in 2003. NASA retired the remaining shuttle craft in 2010 and replaced them with a new vehicle, the Orion, designed to take astronauts back to the moon and perhaps beyond by the year 2020.

Although the manned spaceflight programs have received most of the public attention, unmanned satellites have made enormous strides in advancing communications, meteorology and discoveries about the origins and nature of the universe. Many products now in use in everyday life and in fields such as medicine are products of the space program. Everything from Velcro to heart monitors had its origins in the quest to explore the heavens. The Hubbell telescope has provided scientists with detailed pictures of distant galaxies and start systems.

See Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff and the film of the same title; Norman Mailer, Of A Fire on the Moon; Also dramatic and historically sound are the Tom Hanks film Apollo 13 and his HBO series, From the Earth to the Moon. The NASA site is one of the most popular and frequently visited on the World Wide Web.

The decade of the 1960s began chronologically on January 1, 1961, a month that saw John F. Kennedy inaugurated as president of the United States. Kennedy’s inaugural address was highlighted by the memorable call to arms, “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” In those early days of the Kennedy administration the world seemed relatively calm. Still, the shooting down of the U-2 aircraft over Russia, the continuing threat of nuclear war, and the Cold War environment kept people on edge. The Bay of Pigs fiasco, the erection of the Berlin wall, the Cuban missile crisis and Kennedy’s confrontations with Khrushchev added to the tension that people felt, but the storm had not yet struck. Issues in French Indochina, rioting in the streets, and all the turmoil that has come to characterize the 60s was hardly a whisper on the horizon.

The sixties—as we have come to call the period of upheaval that began in that decade—really began on November 22, 1963, when President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, by Lee Harvey Oswald. Young and vibrant, with a lovely wife and two small children, the President was extremely popular among young Americans. With his untimely death the nation began a descent into one of the most chaotic decades in American history. Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy’s successor, was a powerful President who achieved a great deal of what Kennedy had intended, and much more. His “Great Society” even went a step or two beyond the New Deal in terms of fundamental reform, but lingering doubts over Kennedy’s death remained alive.

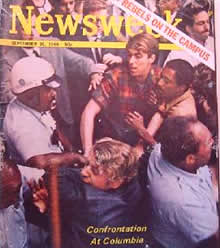

While the fifties were a “laid back” decade, the 1960s were in many ways the opposite. Whereas in the 1950s a popular television program proclaimed that “Father Knows Best,” by the end of the 1960s young people had convinced themselves that father did not know much of anything. Beginning with the “free speech” movement at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1964, a series of rebellions spread from campus to campus. The issues included such matters as women’s rights, the Vietnam War, and the nature of the university itself. Although in retrospect people think of those rebellions in terms of the “anti-war” movement, the student protests were much wider in their scope. In fact, Vietnam protests comprised only a minority of campus disturbances, many of which were directed at societal problems in general.

The more strongly the police reacted to the outbreaks of violence, the more rebellious the students became, and the larger their numbers grew. Across the nation, at hundreds of campuses, buildings were damaged or even destroyed, offices were ransacked, and professors unsympathetic to the students demands were driven from classrooms. In many cases the university was obliged simply to shut down. Following the invasion of Cambodia in 1970, hundreds of campuses were shut down because of student protests.

The more strongly the police reacted to the outbreaks of violence, the more rebellious the students became, and the larger their numbers grew. Across the nation, at hundreds of campuses, buildings were damaged or even destroyed, offices were ransacked, and professors unsympathetic to the students demands were driven from classrooms. In many cases the university was obliged simply to shut down. Following the invasion of Cambodia in 1970, hundreds of campuses were shut down because of student protests.

While cynics may have noted that the level of student protest seemed to rise the closer it got to exam time, the students were often addressing serious issues in a thoughtful manner. On the other hand, many leaders of the student movement—men and women whose names became well known beyond their own campuses—had fairly obvious political agendas; they sometimes seemed to be exploiting the rebellious conditions for their own purposes. The Students for a Democratic Society, SDS, had chapters on many campuses and often orchestrated demonstrations and other disruptive activities.

While often high-minded, the student demonstrations were frequently violent, and they triggered responses from university officials that ranged from acquiescence, to forcible resistance, to what many students perceived as outright oppression, especially when university officials called for help from beyond the campus. When college police forces proved inadequate to handle the growing level of disruption, local police forces and even National Guard troops were called in, with predictable results. Taunted by what they viewed as foul-mouthed, “spoiled brats” of the upper classes who shouted epithets such as “pigs,” and worse, at them, the police often reacted with violence of their own, and the riots often turned bloody, even deadly.

In the best sense, the students and their sympathizers were trying to bring about positive change in American society. They saw themselves as friends of the working classes, a voice for the oppressed, and many of them made positive contributions to the civil rights movement. In the South, black students led the sit-ins and freedom marches and were on the front line when things got rough, as they usually did. For many white students the Vietnam War, while not the only issue, was the biggest issue. Their feelings were probably complicated by the fact that as college students they were deferred from the draft. Draft eligible young man had to remain in good standing, however, and professors often went out of their way to see to it that they did by guaranteeing males with low draft numbers an A grade. The Vietnam protests also called attention to what many saw as an unholy alliance between universities and government, more particularly the military establishment. President Eisenhower had warned the American people of the military-industrial complex in his final address to the nation, and the students recalled that warning. Weapons research, for example, was attacked by students who felt that such work was morally objectionable in a university setting.

President Johnson marked time until his overwhelming reelection over Barry Goldwater in 1964, and then all hell began to break loose. As American troops were sent to Vietnam in ever-increasing numbers, as the civil rights demonstrations grew ever more bloody and violent, and as protests seem to erupt almost on a daily basis, mostly on college campuses, the 60s turned into a time of turmoil and trouble. Although a few early campus rallies were held to support the troops, their days were numbered.

The focus of much unrest on the campuses often dealt with civil rights. For example, in the spring of 1968, Columbia University in New York City erupted in part over plans by the University to build a facility in a housing area in neighboring Harlem. Although the design had been hailed as progressive, it was later judged to be discriminatory, as local residents were to be permitted to use only part of the building. Students soon took over the campus. They occupied administration offices, and eventually caused the university authorities to call for the assistance of the New York City police. Today, in the aftermath of September 11, policemen and firemen and other “first responders” are generally viewed favorably by most Americans of all generations. During the 60s, however, student protesters saw cops, whom the called “pigs,” as the enemy. During an uproar at Boston University, the Boston tactical police were called in and blood was shed as the students resisted the police. At the University of Maryland in College Park, a campus generally not known for political activism, students shut down the main traffic artery of U.S. Highway 1 during rush hour. Fire bombs thrown at ROTC buildings, mass protests, break-ins at draft boards, and marches on the Pentagon and other government officesbecame part of the culture of the 60s.

The year 1968 was the peak of the turmoil as violence broke out in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention. The Chicago police under Mayor Daley carried out what came to be known as a “police riot.” Protesters threw rocks, chunks of concrete and bags of urine at police, and the police responded with force. Blood was shed by demonstrators and occasional innocent bystanders. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy were both assassinated in 1968; it seemed to many that the country had not only lost its moral compass, but was rapidly running amok. The year 1969 saw the inauguration of President Richard Nixon, and as he seemed to be working to try to end the war, the turmoil also seemed to abate for a year.

The year 1968 was the peak of the turmoil as violence broke out in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention. The Chicago police under Mayor Daley carried out what came to be known as a “police riot.” Protesters threw rocks, chunks of concrete and bags of urine at police, and the police responded with force. Blood was shed by demonstrators and occasional innocent bystanders. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy were both assassinated in 1968; it seemed to many that the country had not only lost its moral compass, but was rapidly running amok. The year 1969 saw the inauguration of President Richard Nixon, and as he seemed to be working to try to end the war, the turmoil also seemed to abate for a year.

That period of relative quiet did not last, however. In 1970 when President Nixon authorized an invasion of Cambodia in 1970 to attack communist sanctuaries, four students were shot by National Guard troops at Kent State University in Ohio, and the protests erupted anew. Then came the confusing and frustrating end of the American involvement in Vietnam, followed closely by the growing Watergate scandal, and it seemed that once again, things were as bad as ever. (See The Nixon Years section.)

In 1973 the American POWs came back from Vietnam, Senator John McCain among them, and the escalating Watergate crisis led to Richard Nixon’s resignation in August of 1974. Although South Vietnam fell to the Communists in 1975, and the city of Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City, most Americans viewed it from a distance. In 1976 the country rallied from its despondency in order to celebrate the bicentennial of American independence, and it seemed that by then the 60s were well over. But the nation did not go back to the way it had been in the 1950s—too much had changed. Civil rights legislation opened doors that had been closed for a century. Women had begun to assert themselves and move into areas previously unheard of for the “gentle sex.” Coed dormitories were common on college campuses, thus indicating that the sexual revolution had been, in effect, rubber stamped by university authorities. If parents were distressed, there wasn't much they could do about it; and, in fact, they had lived through the 60s themselves and had been changed by the experience, as had all Americans.

The outcomes are hard to assess. The Vietnam War did come to an end, and substantial progress was made in civil rights and other areas. Perhaps those changes would have come about anyway, maybe more slowly, but maybe without arousing as much resentment. One outcome is certain: the university was changed forever. In the 1950s the university stood in loco parentis—in the place of the parent, knowingly accepting the responsibility not only for students’ education, but for their moral behavior as well. Dormitories were segregated by sex, use of alcohol and drugs was at least officially frowned upon, and male students were allowed to visit females in their dormitories only under controlled conditions. Students were expected to behave in class, obey the college rules and the law, and generally to conduct themselves as ladies and gentlemen.

By 1966 or 1967 all that had begun to change. Although the memory of the student protests seems retroactively to have centered on the Vietnam War, the students were angry about many more things. The university was now obliged to recognize that its students were adults, that they had rights, and that it was not proper for college officials to dictate student lifestyles, no matter how well intentioned such guidance might have been.

Events:

- The Port Huron Statement: Students for a Democratic Society create an agenda.

- The 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago

- The Shootings at Kent State University

College students were not the only ones who rebelled in the 1960s. The civil rights movement raised the consciousness of women as well. When one views the long history of relationships between males and females in various cultures, it becomes immediately apparent that only in recent years has anything like true equality between men and women begun to emerge. Though advances for women in American society have been notable, many other cultures still lag behind—in parts of the world, little progress for women has been made. The history of women in Western society has provided innumerable examples of women who have achieved remarkable things, up to and including the running of entire nations, as was done by Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, who ruled England while her son King Richard Lionheart was off on the Crusades, Queen Elizabeth the Great of Great Britain, Catherine the Great of Russia, and many others. In modern times women like Margaret Thatcher an Angela Merkel have led their nations. Those women are exceptional by almost any definition.

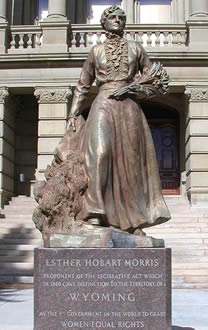

You may recall from early American history the Seneca Falls Convention organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others in 1848. They stated in their declaration that “all men and women are created equal,” a radical notion in its time. From that juncture it took 70 years before women were granted the right to vote in the United States, although some states such as Wyoming, Utah and others afforded women the elective franchise decades before the 19th Amendment was passed.

|

Left: Alice Paul, President of the National Women's Party, salutes the suffrage flag at the 75th Anniversary of the seneca Falls Convention in 1923. She wrote the text of the first Equal Rights Amendment and read it at that meeting. |  |

HBO Iron Jawed Angels Site. Alice Paul's story is portrayed in the film Iron Jawed Angels, with Hillary Swank as Alice Paul. Link to Video Clip of Trailer (apologies for the commercial.) Link to the Women's Rights National |

||

| Right: A statue of Esther Hobart Morris graces the front of the Wyoming State Capitol in Cheyenne. The inscription proudly proclaims that Wyoming was “the first government in the world to grant women equal rights.” |

Alice Paul, pictured above left, was instrumental in the women’s suffrage movement. She and her colleagues worked tirelessly and courageously, even to enduring harsh treatment in prison, to get the 19th (Women’s Suffrage) Amendment passed. Part of her story is portrayed in the film Iron Jawed Angels, with Hillary Swank as Alice Paul.

Giving the women the right to vote, however, did not nearly make women equal in other respects. As late as the 1950s, as one can judge from old television programs, commercials, and newspaper and magazine advertising, women’s roles were decidedly different from those of men in the judgment of a majority of Americans. The appearance of Betty Friedan’s book, The Feminine Mystique, in 1963 began to change those perceptions, however. A few years after the book was published a group of women that included Catherine East (an alumna of Northern Virginia Community College) got together and formed the National Organization for Women. The modern feminist movement was underway.

The majority of Americans probably felt that opportunities for women ought to be expanded, and few could quarrel with the notion of equal pay for equal work, but the feminists had an uphill fight in achieving full equality. The best example of their difficulty is the fact that a constitutional women’s rights amendment, the Equal Rights Amendment, or ERA, although passed by Congress in 1972, was ratified by only 35 states, 3 short of the requisite 38.

Some objections to the equal rights amendment could were unconvincing. For example, some were concerned that privacy issues such as separate public restrooms might be negated by an equal rights amendment. Others argued that the Fourteenth Amendment, although it did not include women at the time it was passed, rendered the necessity of an equal rights amendment extraneous. Article 1 of the Amendment states:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Opponents of the equal rights amendment argued that women were indeed persons and citizens and therefore were fully protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The National Organization for Women argued, on the other hand, that women’s equality needed to be made explicit. The most outspoken opponent of the ERA was conservative lawyer Phyllis Schafly. She argued that ratification of the amendment would mean that women would have to register for the military draft, and that they might lose Social Security benefits for wives and widows. Schafly has been credited with defeating the amendment.

The women’s rights movement has in any case had an enormous impact on opportunities for women. For example, in 1980 approximately 8% of practicing attorneys were women. Today the figure is close to 30%, but almost half of all students in law schools are women. A similar situation exists for women in medicine, where less than 30% of practicing physicians are female, but about half of all medical students are female. Women’s opportunities in the armed forces have expanded enormously, and women comprise well over half of all students in enrolled in colleges and universities. With the exception of the Roman Catholic Church, major religious denominations now regularly ordain women as priests or ministers.

The debate over the proper roles and functions of women is by no means over, however. Attempts to reintroduce an equal rights amendment have occurred, although the issue is clouded by recent debates over the issue of same sex marriages. Both men and women will continue to discuss and argue over the proper roles for females. Social relations between males and females are the product of thousands of years of evolution, and inborn genetic tendencies cannot be wiped out by social action or legislation. When I was teaching a course in Women in American History several years ago (100% of the students in the class were women) I asked the question, “If a boy and girl child were raised in a totally gender neutral environment, would they still gravitate towards traditional male and female roles?” The unanimous response of the class was that they would. Anecdotal evidence, to be sure, but nevertheless interesting.

Although the history of the women’s movement continues, one thing is clear: women in the year 2006 have far more to look forward to in terms of professional and other opportunities than women did in 1960. At that time most Ivy League colleges and the American service academies, Annapolis, West Point, and the Air Force Academy, were still male only. Women have indeed come a long way, but full equality remains to be achieved. They still face the dilemma of the necessity of dual incomes for a family to prosper, even as most women remain the primary caregivers to family members.

Richard Milhous Nixon was elected to Congress from California in 1946 and to the United States Senate in 1950. Selected as General Eisenhower's vice presidential running mate in 1952, Nixon served eight years in that office and was narrowly defeated by John F. Kennedy for President in 1960. Nixon then ran for governor of California in 1962 and was defeated once again. In a bitter farewell to the media he proclaimed that, “You won’t have Richard Nixon to kick around anymore.” Nixon's comeback, however, began when he made a rousing nomination speech for Barry Goldwater for president at the Republican National Convention in 1964.

Following Goldwater's landslide defeat, Nixon worked quietly within the Republican Party and in 1968 was able to secure the nomination for president, running against incumbent Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Humphrey was saddled with Lyndon Johnson's Vietnam War legacy, but the election was nevertheless very close. Former Governor George Wallace of Alabama created a diversion for frustrated Southern conservatives and carried five states in the Electoral College as he ran on the American Independent Party.

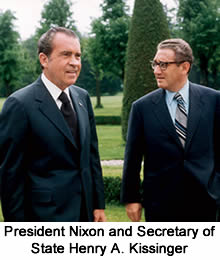

Richard Nixon campaigned on what he called a secret plan to end the Vietnam War, which was in fact nothing more than turning the conduct of the war over to the Vietnamese, in other words “Vietnamization.” He eventually got the United States out of Vietnam and achieved what he called “peace with honor.” (See Vietnam Section.) He and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger, who later became his Secretary of State, saw the Vietnam War as something of a sideshow to the larger issue of the Cold War tension between the United States and Russia and China.

Richard Nixon campaigned on what he called a secret plan to end the Vietnam War, which was in fact nothing more than turning the conduct of the war over to the Vietnamese, in other words “Vietnamization.” He eventually got the United States out of Vietnam and achieved what he called “peace with honor.” (See Vietnam Section.) He and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger, who later became his Secretary of State, saw the Vietnam War as something of a sideshow to the larger issue of the Cold War tension between the United States and Russia and China.

Pursuing a policy which they called “détente,” Kissinger and Nixon sought to reduce tensions among the three major powers. Nixon made a famous visit to Communist China in 1972, the first step in establishing formal diplomatic relations between the two nations. He also had a summit conference with Soviet Premier Aleksey Kosygin in 1972, at which various diplomatic agreements were reached. During his meeting with the Soviet Premier, President Nixon said in a toast, “We should recognize that great nuclear powers have a solemn responsibility to exercise restraint in any crisis, and to take positive action to avert direct confrontation.”

The U.S. entered several treaties with the two Communist nations during Nixon’s first term and supported China’s admission to the United Nations. A Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty was also signed in Moscow. Better relations between the U.S. and China and the Soviets may also have facilitated the end to America’s participation in the Vietnam War. Just after 1972 presidential election Kissinger signed a peace agreement with Le Duc Tho, the North Vietnamese negotiator. Whatever flaws Richard Nixon may have had, his foreign policy achievements have been considered notable. Although tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union remained high, neither side wanted a nuclear war. The consensus among both the American and Russian people was that Nixon's policies had made the world safer.

Watergate. Like his predecessor, Richard Nixon was distracted by the Vietnam War. Well versed in foreign policy matters, Nixon made considerable progress in that area. He instituted a policy that became known as détente, improving relations with the Soviet Union. He also made a well-publicized visit to Communist China, opening a door to further negotiations. He also streamlined many Great Society programs and attempted to shift the burden of and responsibility for much government action from the federal government to the states. As the Vietnam War seemed to be winding down in 1972, and Nixon's “Vietnamization” program was bringing American fighting men home, Nixon was a strong bet for reelection, which he won by a huge landslide. Like Lyndon Johnson's Vietnam policy that overrode his major accomplishments to some extent, one incident in the Nixon administration became the defining episode of his presidency. That episode became known as “Watergate,” named for the office complex and hotel in Washington where a crime was committed.

In June, 1972, a group of overzealous Republican underlings broke into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate office building in Washington in order to bug the phones and were caught and arrested. The actual events of the burglary had little if any impact on the election results, and if the incident had been handled swiftly and properly, the story almost surely would have diewd rapidly. Nixon's staff, however, panicked and began what  eventually became a massive cover-up of the “Watergate” events and their aftermath, and the President himself became deeply involved, even though he apparently had nothing to do with the break-in beforehand.

eventually became a massive cover-up of the “Watergate” events and their aftermath, and the President himself became deeply involved, even though he apparently had nothing to do with the break-in beforehand.

Two Washington Post reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who had covered the original break-in, stayed with the story even after it stopped being interesting to the general public. Following President Nixon's landslide reelection and inauguration on January 20, 1973, the break-in offenders were found guilty and sentenced to jail terms. It was, however, obvious to many, including Woodward and Bernstein, that the story did not end there. The two reporters dug deeper and followed every lead, eventually uncovering the details of what had happened. As additional White House staff members were found to have been involved in the process, the story began to grow. By June, 1973, the Senate had convened a special committee under the leadership of Senator Sam Ervin to investigate the Watergate charges and the White House involvement.

The hearings were broadcast live on television and widely watched—as if it were a live, ongoing soap opera. Top Nixon officials were called the Senate committeeto testify, many were forced to resign, and a number of them eventually served jail terms for obstruction of justice or related offenses. Following the lengthy Senate hearings and subsequent debates in the House, it became clear that President Nixon would be impeached and perhaps convicted of various “high crimes and misdemeanors.” In order to avoid the embarrassment and distraction of a House impeachment process and Senate trial, President Nixon resigned in August, 1974. Thus Vice President Gerald Ford, Whom Nixon had selected to replace vice president Spyro Agnew, who had resigned over financial improprieties, became president of the United States.

Washington Post reporters Woodward and Bernstein were widely praised for their dogged persistence in following the story, the Post won a Pulitzer Prize, and many young Americans came to see investigative journalism as a career that they hoped to pursue. (See Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, All the President’s Men. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974) and the 1976 film of the same name starring Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford, directed by Alan J. Pakula.)

On May 31, 2005, the identity of Woodward and Bernstein's confidential informant known as “Deep Throat” was revealed. He turned out to be W. Mark Felt, deputy director of the FBI at the time. Thus some 30 odd years after the original story broke, Watergate was once again front-page news.

The Watergate episode was the last in a series of events that had begun with Kennedy's assassination in 1963. The Vietnam War, campus revolts, chaos in major cities, two more assassinations and a turbulent political environment were all part of a very troubled decade. In Gerald Ford's address after being sworn in, he stated "My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over... Our Constitution works; our great Republic is a government of laws and not of men." The post-Watergate era had begun, and the 60s were done.

| Postwar Home | Postwar Domestic | Cold War | Updated May 8, 2017 |