| The Native American Story | |||

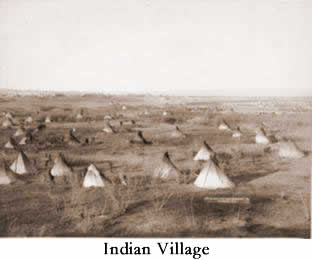

Cowboys and Indians. Of all the tragedies that have befallen America, from slavery to debacles in foreign policy, none is perhaps as relentlessly sad as the plight of the Indians. In 1860 the territory west of the Mississippi contained 60% of America’s land but only 4% of the population. Some 250,000 Indians roamed the Great Plains or lived in settled communities in that area. Before the Civil War they were able to stave off some of the advance of the white man, or at least to keep certain areas to themselves; but once the Civil War ended, the great land rush began to overwhelm them. The history of the interaction between Indians and whites began with Columbus. The story is a long, tragic tale of duplicity, greed, relentless shoving, land grabs, insensitivity, xenophobia and ultimately genocide. The Indians were not without their admirers and defenders, but even “humanitarian” plans to assist Indians often backfired by giving them what they did not want or need. The Indians could have defended themselves, and often tried to do so. Yet they were unable to unify because of their cultural diversity, and thus were divided and conquered. Europeans and Americans made many mistakes in dealing with Indians. They never fully understood the Indians, and many whites still don’t to this day. |

|||

First, whites never understood the complexity and diversity of Indian life and culture. There were hundreds of tribes in North America. They differed more from each other in many cases than did the various ethnic groups that came to America from Europe. Second, whites never fully understood the Indians’ relationship to the land. For many Indians the concept of land “ownership” was foreign or even profane. Indians felt land was there for use, not abuse (although some tribes practiced “slash and burn” agriculture.) They might fight over the use of a piece of land, but not over permanent ownership. Unlimited right of occupancy is not the same thing as sovereignty, a concept alien to Indian thinking. The building of the transcontinental railroads and their branches was the beginning of the end for the Indians’ way of life. By 1900 they had been reduced to often pitiful relics of a once free and proud people. What happened was not unavoidable, but there was a certain inevitability about the tragedy stemming from cultural insensitivity. Misunderstanding and error existed on both sides, and although the moral claim against the white settlers and the government is strong and irrefutable, the Indians managed at times to make things worse for themselves. That is not to say in any way that the Indians were responsible for what happened—they were victims by any definition—but if they had been more clever, or perceptive, or if they had put aside inter-tribal animosities and organized themselves, they might have been able to reduce the damage. The Indians have told their own story—sadly and eloquently—but perhaps the best thing that can be said about the history of the American Indian is that it is not yet over. (See Indian Stories, Appendix.) Indian warfare operated under different rules from those of Europe, and that created further misunderstanding and hatred. Indians were hard fighters who felt that a brave enemy was a worthy opponent, and that those who could withstand pain were the bravest of all. That aspect in Indian fighting often struck the Europeans as torture. Captured enemy warriors were “allowed” to die in painful ways in order to demonstrate their courage. Further, the wearing of enemy clothing was for Indians a sign of respect, but it was seen by American soldiers as a sign of contempt or mockery when Indians donned the uniforms of captured or slain U.S. Army troops or officers. Capturing enemy women and children was a method Indians sometimes used to increase their own tribes, a practice they felt necessary as a result of losses from warfare or disease. Paradoxically, Indians loved children, but often kidnapped them. Captured women, including whites, were often welcomed into the tribe as brothers or sisters and were generally treated kindly. Trying to convert Indians to agriculture was often a failure. Many Indian males considered farming women’s work, and refused to do it. (That fact also made Indians in colonial times quite useless as slaves; they were quick to escape and difficult to recover.) Those who tried farming, for example, were scorned and even attacked by others. In one case when government agents tried to teach a tribe how to plow up the ground in order to plant crops, the Indians rejected the advice. The tribe worshiped the earth, and their leaders responded, “Would I stick a knife in my mother’s breast?” The agent tried another tack by suggesting burning off the surface grass before planting. To that suggestion the Indians responded, “Would we set fire to our mother’s hair?” Many attempts were made to convert Indians to Christianity, sometimes with apparent success. But in the end, as one historian of Indian culture has said, it is very difficult to convert Indians into anything other than Indians! Just as Indians have been called “Americanizers” of the European settlers, so were the Indians profoundly changed by their contact with whites. The four factors introduced by whites that most influenced the Indians were:

None of those were necessarily deliberately introduced to hurt or help Indians, except for alcohol. American “diplomacy,” however, was deliberate. It failed by treating Indian tribes as if they were sovereign, European-style nations. Chiefs were not “political” leaders in the sense that presidents and kings are political leaders. True, they often followed quasi-democratic processes in electing chiefs or sachems, but the chiefs did not have the power (nor the right, perhaps) to sign treaties that bound all the members of their tribes. Even if they wanted to, Indian chiefs who signed treaties could not enforce them, nor could they control all their members, any more than the U.S. government could keep miners and settlers off the reservations. Because they were an additional obstacle to further white migration, the Native Americans lost their lands despite their attempts to defend it, and their cultures were radically changed by the end of the 19th century. By 1867 many of the nearly a quarter of a million Indians in the western half of the U.S. were originally from the East, displaced by relentless waves of settlers. Others were native to the region, with cultures suited to their environments. By the 1880s, confrontations with still more white settlers had driven the Indians onto increasingly smaller reservations, and diseases introduced by whites had decimated the California Indians and others. By the 1890s the Indian cultures had crumbled. Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce. The Nez Perce (Indian name Nimi'ipuu) were a peaceful tribe. Although they considered themselves warriors, they did not practice scalping. They lived in northern Idaho and sometimes functioned as intermediaries between western coastal tribes and prairie Indians. They had very strong feelings of attachment to their land, which included the belief that cultivating the earth was wrong. When pressured to move, they refused to give up their territory in Idaho. An old Nez Perce chief named Joseph had a son named Chief Thunder Rolling in the Mountain. who became Young Chief Joseph. One of the most dignified Americans ever, he was a wise and gentle man. When one of his braves was murdered, Joseph pronounced a “life” sentence on the murderer; that is, he pardoned the enemy brave, who would otherwise have been killed. An early treaty had awarded the Wallowa Valley to the government, but Young Joseph did not want to leave. He had thousands of horses, which equated to wealth, and there was no room for them on the reservation. Joseph agreed to leave the reservation, but hundreds of his horses were stolen, and in retaliation, 18 whites were killed. Joseph turned out to be a prodigious fighter who was pursued by General O. O. Howard. Joseph finally decided to lead his band to Canada, and fought his way over 1000 “mountain miles.” Joseph’s chiefs included Looking Glass, White Bird and Ta Hool Hool Shute. Although the Nez Perce fought with great skill, they were finally obliged to surrender about 30 miles from the Canadian border. Finally willing to stop fighting, Joseph made a speech that was recorded by an Army officer in General Howard’s command. |

|||

|

Chief Joseph’s Speech “Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. Ta Hool Hool Shute who led the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have some time to look for my children, and see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.” Chief Joseph |

Today the population of the Nez Perce tribe is approximately 3,400. The tribal reservation is located in Lapwai, Idaho. You can find information about the Nez Perce on their website (www.nezperce.org), as you can for hundreds of other Native American tribes as well. |

Sitting Bull in 1878 |

| On the Nez Perce tribal reservation in Lapwai, Idaho, the tribe has developed a new breed of horse in recent years, a cross between an appaloosa mare and a rare central Asian breed. Indians were among the finest horse people on Earth, sometimes called the finest light cavalry in the history of warfare. | |||

Little Bighorn. In 1876 one of the most famous Indian battles took place along the Little Bighorn River in Montana. Colonel George Armstrong Custer attacked a band of Sioux Indians under Chief Sitting Bull, not realizing that he was badly outnumbered. Custer had divided his command into three groups, and his 210 troops of the 7th Cavalry became isolated. They were overrun by a combined force of Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. Custer and all of his men were killed in one of the worst defeats in the history of the U.S. Army. For years the Indian side of the battle was not well known, and the historic site was known as the Custer Battlefield. The story was passed down orally among Sioux and Cheyenne tribesman, however, and in 1996 the National Park Service, recognizing the need to honor Native American history, changed the name of the site of the Little Bighorn Battlefield. Today visitors to the site can hear stories told by Native Americans as part of the presentations of the historic event. Three excellent books on the epic battle:

|

|||

| Chronological Summary of the Native American Story | |

1850 |

Whites outnumber Indians by 20 million (mostly east of the Mississippi) to about 360,000. By now the idea of a well-defined reservation is accepted, but railroads cut into reservation territory. Gold rushes also put whites and Indians into conflict, as do growing numbers of immigrants who cross the Atlantic by steamship. |

1851 |

Great Council at Fort Laramie arranged by Thomas Fitzpatrick (Broken Hand). Attended by 8-12,000 Indians—Shoshone, Sioux, Crow, Arikara, Assiniboins, Arapahoes, etc. Twenty days of meetings. Indians warned not to attack settlers on Oregon Trail, avoid fights with each other. U.S. will maintain forts along the trail and provide $50,000 per year in food, etc. Chiefs accept boundaries and promise to be tolerant of settlers, but then the gold rush gears up. |

1853 |

Ft. Benton Conference. When peace is urged, Chiefs say young braves need to fight to demonstrate heroism. Hunting tribes asked to become farmers—they say it won't work. Blackfoot Treaty is the result. |

1861-65 |

Civil War. The Five Civilized Tribes join the Confederacy (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, Choctaw, Seminole.) The Indians confuse the issues of war somewhat, are apt to change sides, shoot prisoners, etc. They pay a price after the war. During the Civil War Indian policy is run by the military. |

1864 |

The Sand Creek Massacre by Colorado militia led by Colonel John Chivington, a Methodist minister. The Colorado Third Regiment is organized to fight for the Union, but Colorado settlers are being bothered by bands of Cheyenne, Arapahoes and Utes. The Fort Wise Treaty is signed, but the Indians later complain of abuse by settlers—horse stealing, etc. Indians approach army for relief, but get none and go on warpath. Chivington’s expedition is deliberately punitive, one of the ghastliest of the whole period. The Cheyennes under Black Kettle try to negotiate, but Colorado governor declares state of war. Cheyennes told to wait at Sand Creek. Guides tell Chivington to use discretion, but he attacks; Indians show great bravery, but 450 are killed, including women and children, all under a flag of truce. Charles Bent, a Cheyenne, spends the rest of his life hunting down, torturing and killing whites. Chivington later shows off his collection of 1,000 scalps in Denver. |

1865-70 |

Radicals in Congress try to resolve Indian question fairly. Reformers, many of them former abolitionists, see Indians as "noble savages" and reservations as "prisons" into which civilization cannot penetrate. Others feel Indians can be assimilated like other nationalities. But a majority of Americans feel a reservation policy is the only feasible solution. Regional attitudes toward Indians differ. Westerners just see the savage and are furious at "the foolishly sentimental attitude of eastern reformers." They have seen Indian barbarity first hand—stripping bodies, torture, rape, kidnapping children. Easterners do not blame Indians alone. |

1866 |

The Fetterman massacre. Fort Kearney is built on the Bozeman Trail to protect it. Red Cloud attacks wood gathering parties to lure soldiers out of the fort. When 80 soldiers under Captain Fetterman chase the raiding Indians they are surrounded by 2000 Sioux, and all are killed. |

1867 |

Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho, Cheyenne accept lands in Oklahoma. Sioux agree to live in Black Hills, which they consider sacred. Congress publishes "Report on the Condition of the Indian Tribes," which leads to creation of the Indian Peace Commission. The Commission undercuts the Army. There is also much debate over whether the Indian Bureau is to be in the Interior Department or the Army. |

1872-74 |

Nine million buffalo are killed by white hunters for furs, trophies. Carcasses left to rot after valuable parts removed. Piles of buffalo skins hundreds of yards long are stacked next to railroad pickup locations. |

1870 |

Red Cloud and Red Dog make speeches at the Grand Opera House in NYC. Other visits follow—much support gained for reforms in Indian affairs. |

1871-1872 |

Modoc Wars in California. The Modocs have been shuttled to many reservations. They rebel and fight out of lava beds. Modoc Chief Kintpuash (Captain Jack) kills many soldiers, including a peace commissioner and General Canby; Kintpuash then wears Canby's uniform. Kintpuash is hanged after artillery drives Indians out of village. Commissioner Meachem, who was left for dead, later speaks in Boston. |

1874-75 |

Red River War. General Philip Sheridan uses convergence tactics to scatter Southwest Indians; terms reached in 1875. |

1876-77 |

The Great Sioux War. After forts destroyed, new one to be built in Black Hills by Custer's command. Their discovery of gold triggers a new rush by settlers. |

1876 |

Battle of the Little Big Horn. Custer's 250 against 2500. Indians fail to capitalize on victory, scatter. Sitting Bull escapes to continue the Indian wars. After the Great Sioux War virtually all the Indians are gathered in Indian Territory (Oklahoma.) By 1879 President Hayes announces that the policy is to Americanize all Indians, thus eliminating the need for reservations. |

1879 |

Utes give up land in Western Colorado. |

1881 |

Indians have 155 million acres of land for about 190,000 Indians. By 1900 it is down to 84 million acres. |

1884-86 |

Supreme Court says Indians are not citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment. |

1886 |

Capture of Geronimo, a Chiricahua Apache. He had continued to cause trouble in the Southwest. |

1887 |

The Dawes Severalty Act: Meant to introduce Indians to individual land culture. "Disastrous" results. Communal land stifles self-improvement, it is thought. Indians given 160-acre lots, supposedly protected for 25 years by the government. Fifty years later 2/3 of Dawes land grants owned by whites. |

1890 |

Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Paiute shaman Wovoka practices mysticism, teaches the ghost dance, calls himself the Indian messiah, promises to lead Indians out of bondage and says whites will be destroyed. As movement spreads, white fear grows. Sitting Bull arrested and killed. Soldiers surround Indian camp, shooting breaks out and over 300 Indians are killed, including women and children. |

1901 |

Citizenship extended to the Five Civilized Tribes in Oklahoma: Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole. |

1906 |

Burke Act. Indians can be instant citizens when they “voluntarily take up a residence separate and apart from any tribe of Indians therein and adopt the habits of civilized life.” |

1887-1934 |

Indians lose 86 million acres of land. |

1980 |

Two million Indians exist in the U.S., 7 million Americans claim to have Indian blood. Today the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs provides various services directly or through contracts, grants, or compacts to 562 Federally recognized Indian tribes who have a population of about 1.9 million American Indian and Alaska Natives. (www.doi.gov/bia/index.html.) |

Gilded Age Home | The American West | Indian Stories by Indians | Reading About Indians | Native American Web Sites | Updated January 28, 2018 |

|