| INTRODUCTION TO AMERICAN HISTORY |

“History is our collective memory. If we are deprived of our memory we are in danger of becoming a large, dangerous idiot, thrashing blindly about, with only the dimmest understanding of the ideals and principles that formed us as a people, and that we have constantly to reinterpret and affirm if we are to preserve a sense of our own identity.” —Page Smith, from A People’s History of the United States |

“If you don't know history, you don't know anything; you're a leaf that doesn't know it's part of a tree.” —Michael Crichton in Timeline |

“I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided, and that is the lamp of experience." —Patrick Henry, Speech, 1775 |

“A nation that forgets its past can function no better than an individual with amnesia.” —David McCullough |

Why Study History?

Henry Ford once said, “History is more or less bunk.” To an industrialist who revolutionized the automobile industry by discarding old methods and creating new ones, the past may have seemed irrelevant. But it is clear that Henry Ford understood thoroughly what had occurred in industrial America before his time when he developed the assembly line and produced an automobile that most working Americans could afford. Whether he was aware of it or not, Henry Ford used his understanding of the past to create a better future. (In fact, what Henry Ford really meant was that history as being taught in the early 1900s was bunk.)

Ford’s opinion aside, history is about understanding. It would be easy to say that “in these critical times” we need to know more about our history as a nation. But even a cursory study of America’s past reveals that relatively few periods in our history have not found us in the midst of one crisis or another—economic, constitutional, political, or military. We have often used the calm times to prepare for the inevitable storms, and in those calm times we ought to try to predict when the next storm will arise, or at least consider how we might cope with it.

Because the best predictor of the future is the record of the past, we can learn much of value even when the need for such learning is not immediately apparent. Once the inevitable crisis is upon us, it may be difficult to reflect soberly on what we can learn from the past. As philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel said, “Amid the pressure of great events, a general principle gives no help.” A modern version of that dictum, often used in a military context, goes something like this: “It’s hard to remember that your mission is to drain the swamp when you’re up to your butt in alligators.” In any case, without looking backward, we may find the road ahead quite murky.

No matter how much American history keeps presenting us with trying new situations, we discover from looking backward even to colonial times that we have met comparable challenges before. Conditions change, technology provides new resources, populations grow and shift, and new demographics alter the face of America. Yet no matter how much we change as a nation, we are still influenced by our past. The Puritans, the early settlers, founding fathers, pioneer men and women, Blacks, Native Americans, Chinese laborers, Hispanics, Portuguese, eastern Europeans, Jews, Muslims, Vietnamese—all kinds of Americans from our recent and distant past—still speak to us in clear voices about their contributions to the character of this great nation and the ways in which we have tried to resolve differences among ourselves and with the rest of the world.

Everything we are and hope to be as Americans is rooted in our past. Our religious, political, social and economic development proceeded according to a pattern—whether random or cyclical—and those patterns are intelligible to us when we study our heritage. The men who wrote our timeless Constitution, the most profound political document ever produced by man, were acutely aware of what had gone before as they fashioned a document that would serve millions of Americans yet unborn. The power of our form of government comes from the fact that our fathers took the best of the past and built upon it.

Our success as a nation depends on how well we know ourselves, and that knowledge can only come from knowing our history. Without hindsight we are blind to the future; without comprehending our past—the positive and negative aspects—we can never truly know where we want to go. History is an essential element of the chain of events that defines our road ahead. As the quotations at the top of this section suggest, we are all part of the American tree, and its roots go very deep.

What Is American History About?

For most historians the fundamental question to be answered in the study of history is, "What really happened?" In studying American history we know a great deal about "what happened," and relatively few serious questions exist about the basic facts of American history. We have fought wars, elected presidents, built factories, cultivated millions of acres, produced enormous wealth, seen immigrants flock to our shores, driven the Indians off the plains and onto reservations, ended slavery, and so on. If our concern with history stopped there, we would mere chronology. The study of history goes beyond chronology and into the how and why things happened in the past. History, in other words, soon becomes complicated.

We know, for example, that the American Revolutionary War began when shots were fired at Lexington and Concord in 1775. We are still undecided, however, about the exact nature of that experience—was it really a revolution, or merely a transfer of power across the Atlantic Ocean? We know that the Japanese empire bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, but controversies have raged over the causes of that aggression, and about how much was known of the impending attack on that fateful morning. The real causes of the Civil War continue to be debated, and hundreds of books have been written about the events surrrounding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. As soon as we begin to ask how and why things happened, consensus disappears.

Sometimes explanations for historical events breed conspiracy theories. Did President Roosevelt really know about the impending attack on Pearl Harbor? Was the CIA involved in President Kennedy's assassination? Did we really land on the moon? Was the plot to destroy the World Trade Center really hatched in Washington by our government? Is the earth really round? Conspiracy theories spread rapidly and die hard even when overwhelming evidence to the contrary exists. (There really is a Flat Earth Society.) Our job as historians is to penetrate the myths about our past in order to discover the real truth of American history.

Our Roots Are Deep and Wide: America and the Rest of the World

American history did not occur in a vacuum. Thousands of years of human history preceded the discovery and colonization of the North American continent, and much of that prior history had a direct or indirect bearing on how this nation was formed. Some historians view American history as an extension of the history of Europe, or of the history of the “Western world.” On the other hand, some claim that American history tells a tale that has no real parallel in the histories of other nations, even though Americans have much in common with other peoples. That view is sometimes referred to as “American exceptionalism,” the idea that America’s history is unique. Both views have some merit, but the important point to remember is that Americans sometimes fail to see themselves in their proper relationship to the rest of the world, often at their own peril. In other words, we are not alone.

As we shall see, American history has strands that find their roots in the ancient worlds of Greece and Rome. Indeed, the “American Empire” has been compared—for better or worse—with the Roman Empire, and much of our political philosophy, as well as our literary and social concepts, can be traced to the ancient Greeks. The scientific discoveries associated with the Renaissance were frequently based in the work of Muslim scholars and historians, who kept classical ideas of the ancient world alive during Europe’s so-called Dark Ages. The advances of the Renaissance led in turn to the discovery and exploration of new worlds, of which our ancestors were the beneficiaries.

When the Europeans left their homes to come to America they did not leave everything behind, but brought with them their religions, their cultural ideas, their values and concepts of justice and freedom. They named their colonies, cities, towns, and villages after their Old World homes and in some measure tried to recreate them on virgin soil. For reasons we will discuss later, that attempt at re-creation was futile if not actually undesirable, for the movement to the New World was inevitably a transforming experience. But the colonizers felt their roots deeply, and those roots persisted in influencing their decisions for generations. American history was shaped by strong currents that go back hundreds or even thousands of years. We are connected to the past as surely as the roots of a tree are anchored in the ground. And while the investigation of all that prehistory is essential for a full understanding of the modern world, most of it necessarily lies behind the scope of this basic course. No matter how much we read or study, we are never capable of seeing more than a small portion of the great panorama that is the history of the United States, which, even for us, is just a small part of the greater history of the world.

Although America is necessarily connected with the rest of the world in profound ways, for significant periods in American history events in this country occurred without being influenced from without. The colonists who arrived here in the 17th century, for example, were largely untouched by events occurring elsewhere except as they stimulated further emigration from Europe. In the 18th century, however, a series of dynastic wars among the European powers were often played out on the battlefields of North America. In the latter decades of the century, the influences of the American and French revolutions were felt strongly on both sides of the Atlantic.

Later, as America filled up its frontiers, 19th-century Americans went about their business without much reference to the rest of the world, except, of course, for the influence of millions of refugees and immigrants who poured in through Ellis Island and other ports in the latter decades. Because the European world was relatively free from conflict during the so-called “Hundred Years’ Peace,” America was relatively untouched by major events beyond our shores. Eventually, perhaps inevitably, America was dragged into conflicts with foreign powers, but those periods were typically followed by periods of withdrawal—or isolation, as it is sometimes called. It was only during the 20th century, beginning with World War I, that the United States became a major player on the international scene. Since the end of World War II America has been a dominant force in international affairs.

To go back to our origins, however, we may start with the proposition that American history did not begin with Jamestown, nor the Spanish settlement of North America, nor Columbus, nor even with the arrival of the Native Americans. For America is a Western nation, a nation whose roots lie deeply in Europe, albeit with powerful strains of Native American, African, and Asian cultures mixed in. America is an outgrowth of the evolution of European society and culture. From our politics to our religion to our economic and social behavior, we follow patterns that emerged over time from the ancient civilizations of the Western world—Greece, Rome, the Middle East, and the barbarian tribes that ranged across northern Europe before the rise of the Roman Republic and the Greek city-states.

Our principal religion is Christianity. Our drama is tinged with the influence of Greek tragedy. Our laws have grown out of the experiences of the Roman Republic, the Greek city-state and English common law. Our philosophy is heavily derived from Plato and Aristotle, and our science and mathematics also stem from the ancient world, often via Islamic and African scholars who picked up long-lost threads and wove them into new shapes that were embraced by Europeans during and after the Renaissance. Those developments in science and mathematics made possible the great age of exploration, which led to the discovery of America (or “rediscovery” if you prefer) by Columbus and his successors.

Following are some of the ways in which the pre-Columbian world touched American history:

- Religious: The Judeo-Christian heritage of America is strong and still has enormous influence over our attitudes and beliefs. The Crusades, the Reformation, and the entire religious history of Europe are part of the background of America. Our religious heritage helps determine our relationships with the rest of the world.

- Political: Early concepts of democracy were Greek—the funeral oration of Pericles from Thucydides could be used at a present-day 4th of July celebration. The Roman Republic was the last great republic before the United States. The founding fathers were aware of that history and used it in making their revolution and writing our Constitution.

- Philosophical: As Alfred North Whitehead remarked, “The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” In other words, our ideas of self, society, and government, and the nature of our universe, have roots in ancient and medieval philosophies.

- Cultural: Our poetry, drama, music, literature, and language are all part of the Western European heritage. We formed our own culture, but it was informed by all that had gone before.

- Economic: From mercantilist beginnings America became the most successful capitalist nation in the history of the world, partly because of our adoption of the Protestant (Puritan) work ethic and the notion that God helps those who help themselves. Banks, publicly owned stock companies, corporations, insurance companies, and other economic enterprise systems had their roots in Europe, but were refined and expanded in America.

In beginning our study of American history, then, it is important to enter it with an open mind and a broad vision. This introductory text of necessity covers only the surface of America's past. As one delves deeper into the course our nation has taken from its origins to the present day, one's focus must narrow. More advanced courses in history dig deeper into history's different components. Many hundreds of historical works cover specific events and individuals in great detail. Political figures like Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Wilson, and both Roosevelts have attracted dozens of fine authors, as have inventors, scientists, artists, athletes and countless other figures. The American Civil War alone has bred tens of thousands of books, and they are still coming out. In studying history we quickly realize that the overall picture is even larger than it may at first seem; in our first journey through the past we will leave out many details. This is just the beginning.

Prehistory: The Origins of the Age of Discovery

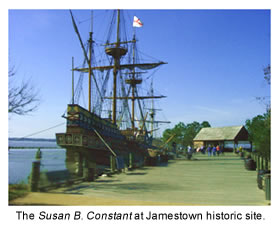

The year 1607, which marks the settlement of Jamestown, the first permanent English colony in North America, is certainly one of the more significant dates in early American history. It would be wrong, however, to think that American history started there—after all, many peoples were here before the English. Spaniards roamed parts of North America 100 years before the English arrived, and as is well known, Native Americans were here tens of thousands of years before that.

As we have already noted, the origins of American history go back in other directions besides those that lead to what actually happened on this continent. The explorations of Christopher Columbus began an earlier phase of the story of the settlement of the New World, but that story also had roots that go even further back in time. The scientific discoveries of the Renaissance that made oceanic travel possible are part of the background of the discovery story. The Crusades generated interest among the the European powers in trading with the Far East, which in turn led to the desire for better communication between Europe and Asia.

For reasons we will not take time to explore, Pope Urban II ordered the first Crusade in the year 1099. The Crusades lasted for about 200 years, and during part of that time the Holy Land, the area that is now Israel, was occupied by European princes and their followers who tried to organize a Christian empire in the midst of the Islamic world. One byproduct of that occupation was enhanced contact with traders and travelers from the Far East who journeyed overland to the Mediterranean region, bringing silks, spices and other goods. Much of the commerce between the Middle East and Western Europe went through Italy, where merchants found that dealing with goods originating in Asia was quite profitable. Thus it was no coincidence that the first mariner to set out for Asia across the Atlantic was Italian.

The difficulty with trading with the Far East was that the overland routes were long and tedious, and caravans were subject to various taxes and raids along the way. Conducting commerce with the Far East by ship was faster and safer, though the trip was long. For a time traders seeking to deal with Asia sailed around the Horn of Africa, along its East Coast and then across the Indian Ocean until they reached ports and East and Southeast Asia.

Sea borne travel was at that time still dangerous because of limited knowledge of celestial navigation and the lack of accurate timepieces, which combined to make any ocean voyage that got outside the sight of land quite precarious. But with the Renaissance came advances in knowledge of navigation and the ability to determine longitude, which meant that vessels could proceed farther out to sea and maintain some sense of their whereabouts. Since the trip around Africa was long and difficult, and since it was known (despite myths to the contrary) that the world was round, sailors came to imagine traveling to the far east by sailing west.

Those ideas, of course, led to Columbus’s discovery of what he thought was a direct route to India, but which was actually the ocean path to America.

The Crusades influenced events America's roots in another way. In our discussion of the Reformation we will point out that Martin Luther's frustrations with the Roman Church were a product of corruption which had in part begun during the time of the Crusades. Crusaders who died fighting in for Christ were granted by Pope plenary indulgences, which meant that they had a direct, rapid path to heaven in case of their death while fighting for God.

Since the Crusades were expensive, in order to raise funds to support those journeys, indulgences were eventually offered to those who supported the Crusades financially. That idea soon evolved into the concept of granting indulgences for other good works, such as supporting the building of St. Peter's in Rome. By Luther's time, indulgences were being sold with all the crassness that suggested the church was selling tickets to heaven.

Martin Luther found those and other practices of the church corrupt and issued his famous complaints against the church; thus began the Protestant Reformation. It often happens that once a revolution has begun, it is difficult to contain it, and from Martin Luther's first break with the Church of Rome, various other reformers took his ideas off in even more radical directions. Even in his own lifetime, Martin Luther was involved in disputes with other reform theologians, not only with Catholic authorities.

One of the defenders of the church against what was seen as the heresies of Martin Luther was King Henry VIII of England, who, in appreciation for his writing of a defense of the Roman Church, was granted the title of “Defender of the Faith,” an appellation which British monarchs carry to this day. For reasons explore more fully below, Henry eventually became disgruntled with the pope, and therefore separated his church from Rome, an event known as the English Reformation. But some of the advocates of Protestant Reformation ideas took more extreme positions, saying that the Anglican Church had done little to reform itself except to replace the Pope as the head of the church with the King of England. Some of those reformers were upset by what they called “remnants of popery,” and sought to purify the Anglican Church from its “Romish” influences. Important among such groups were the Puritans who would eventually settle Massachusetts Bay.

The colonization of North America by the English which took root at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 was also driven by additional forces emanating from the Crusades, namely, the Spanish and Portuguese conquests of Central and South America which had brought them enormous wealth. As more and more nations sought to expand trade as the key to national wealth, and saw acquisition of colonies as a way to facilitate that trade, exploration and colonization were advanced by ideas that have come to be identified as capitalism.

Along with the events described above are, of course, other major factors such as the religious movement begun by Mohammed which resulted in the religion of Islam; the rise and decline of the Roman Empire, which included the spreading of Christianity throughout most of the European world; the Viking explorations and Norman conquest of England. All those things and more have contributed to the chain of events which resulted in the nation we see today.

A Beginning, A Middle and an End

One way to look at history—perhaps the easiest way—is to view it as a narrative. Rather than trying to learn history as a series of more or less unconnected events, if we see it as a story with a plot, much as a novel or a movie, we can grasp the big picture as a frame in which we can look at particular events.

Early American history is indeed a story with a beginning, a middle and an end. The plot of the story is full of interesting characters, conflict, resolution of conflict, more conflict and more resolution. Since we know the end of the story of early America, as it turned out in 1865, the dramatic tension may be slight. But while it was happening, the outcome was uncertain, and in no way inevitable. In the beginning they came—in a trickle at first, and then a growing tide of humanity escaping from the frustrations of life in the old country. They saw—they liked what they saw, and more came and spread inward and up and down the coasts, along rivers, into the valleys and over the mountains. They conquered—they conquered their loneliness, they conquered the land, they conquered the rivers and the fields and the forests, and they conquered the natives. And within 150 years the first part of the American story was ending, and a new chapter was beginning |

The Plot Thickens

The second part of the story is that of revolution, which began when the frustrations of Europe reached America’s shores. The new country in the old country had parted ways—partly because of distance and the newness of life in America, but also because the old systems did not work here. Life was different, labor was more valuable, land more plentiful, opportunities less restricted. Although the differences between the Old World and the New were not at first irreconcilable, they were sharp. Had relations been managed better from the British side, and had Americans been less impatient, things might have been resolve peacefully, although the eventual independence of America over time must be seen as having been inevitable. In any case, the protest began, spread to open defiance and finally to armed rebellion, and the war came.

The revolutionary war was not the bloodiest in American history in absolute terms, but in terms of its impact on the population, the percentage of people who participated and died, it was a great war. It was fought badly for the most part on both sides, and although George Washington was not a great general on the model of Napoleon or Caesar or Lee, he managed to hold the cause together until the British tired of the game. With help from the French and pressure from the other European nations, the British let go of their rebellious cousins.

The second part of this chapter was the creation of a government and a nation. Compared with conditions which have accompanied most modern revolutions, the Americans had the extraordinary luxury of a period of six years during which Europe ignored the new nation. Absent any threats from without, America was allowed to find its own constitutional destiny. The original government created, the Articles of Confederation, could not have lasted as the nation expanded—there was too little power at the center; something more substantial, more permanent, more profound was required, and in Philadelphia in 1787 what has been called a “miracle” was wrought, and the Constitution was written.

Under Washington’s leadership the new ship of state found its way, though the waters were often rough and choppy. Turmoil erupted in Europe just as the new government under the Constitution began, and the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars threatened the stability of the nation, But with firm hands on the helm, the ship kept on course and did not founder.

The first great test came in 1800, when political power changed hands peaceably for the first time in the modern world. So tense had been the politics in the 1790's that at least one historian has opined that the nation might have descended into Civil War had Jefferson's Republicans not won the election of 1800. With that victory a new phase of American history began—the Jeffersonian-Jacksonian era.

During Jefferson’s two terms as president the nation spread and prospered, but also slowly drifted towards war. His successor, James Madison, challenged the British, and the War of 1812, sometimes called the second war for independence, was fought. Again, it was fought badly if valiantly by the Americans, but the British, fatigued from years of struggling against Napoleon, were willing to call it quits with after having punished the Americans by burning their capital.

Then follow what has become known as the “era of good feelings,” although sectional tensions over economic issues, including slavery, were developing underneath the placid surface. In 1828 a new revolution was underway. The “Age of Jackson” is also known as the age of the common man—American democracy spread from wealthy landowners to virtually all adult white males. During the 1820s and 30s American democracy move forward at a steady pace, even as it left women and blacks behind. In 1831 Alexis de Tocqueville visited America and wrote his famous “Democracy in America,” an explanatory history of the nation which emphasized the spirit of egalitarianism that pervaded everything American, with the notable exception of slavery.

The final chapter in early American history began with expansion, which led to further struggles over slavery and how to deal with the peculiar institution. War with Mexico expanded the country to the coast and opened new areas of conflict. The most difficult issue to resolve—largely because it was embedded in the Constitution—continued to be slavery. Through the 1850s virtually every public issue of national import was related to it, and as 1860 approached, the tension on both sides became unbearable.

The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 signaled the beginning of the end of early American history, and the greatest war our nation has ever indulged in began. It was fought with the ferocity only possible when brother fights brother and friend fights friend. The devastation in the South was enormous, the losses grievous on both sides, but in 1865 the end of the end came when Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox.

Thus the first half of American history drew to a close, and as northerners and Southerners buried their dead, they looked ahead to new and unforeseen challenges as America entered the modern world.

| Take a Trip from Coast to Coast over America |

| Sage History Home | Colonial America | Colonies & Empire | American Revolution |

| Updated November 3, 2021 | |||