Important Battles of World War II: The Pacific Theater

The literature on World War II is vast. The purpose of this section of the website is not to provide a detailed account of the monumental struggle that covered most of the globe. It is designed to provide a brief overview of the major battles and issues appropriate for an introductory course in American history. Throughout World War II portion of the site are references to published works, films and other websites pertaining to the issues being covered in each section. Additional material will be added as the site is updated from time to time.

As mentioned in the introductory pages, World War II can be considered to separate wars being fought at the same time. For example, the Soviet Union did not become engaged in a Japanese war until hours after Japan had surrendered. Conversely, Japanese forces did not participate in the European war, and German and Italian forces were not involved in the Asian theater. Nevertheless, there were overlapping concerns that covered both sections, such as the demands by area commanders for additional equipment, supplies, and men. There were also political issues that arose from time to time and were often discussed among meetings between men like Chiang Kai-shek, Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill, and de Gualle.

It is important to keep in mind that, therefore, that the European and Pacific wars were not fought in a vacuum. What incurred in one area often impacted another as dramatic changes in the situation on the battlefields frequently called for a realignment of available combat resources. In addition, many important if not crucial battles were fought all over the world before the Americans entered the war on December 8, 1941, or in in areas where Americans were not involved. A few examples would include:

- The Battle of Britain, the air war over the English Channel and the British Isles, about which Churchill said, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

- The Battle of Stalingrad, 1942–43, in which the Germans lost an army of 600,000—“The Forsaken Army”—at least partially because of Hitler’s refusal to let his generals pull back.

- The Battle of the Atlantic prior to America's entry. The Royal Navy against German submarines and surface vessels, of which the sinking of the Bismarck was a high point.

- The Battle of France, 1940, when the Germans went around the Maginot line and defeated France in a matter of weeks.

- The British Army with Australian and Indian divisions in South and Southeast Asia, and the fighting in China that went on until 1945.

First Strike in the Pacific: PEARL HARBOR

Japanese aggression began in the early 1930s as Japan sought to extend her influence throughout the Far East. Troubles between the United States and Japan had been brewing for some time, largely over the treatment of Japanese immigrants in America and the generally distant policy toward Japan pursued in Washington. The Japanese were determined to become a major sea power and renounced  the Washington Naval Conference agreements in the early 1930s. By 1937 Japan was conducting an aggressive war against China and was trading with the United States for steel and other raw materials she needed to fuel her war machine. An American ship was attacked by Japanese aircraft in 1937, but the Japanese apologized and paid reparations. Nevertheless, tensions continued to build throughout 1940 and 1941.

the Washington Naval Conference agreements in the early 1930s. By 1937 Japan was conducting an aggressive war against China and was trading with the United States for steel and other raw materials she needed to fuel her war machine. An American ship was attacked by Japanese aircraft in 1937, but the Japanese apologized and paid reparations. Nevertheless, tensions continued to build throughout 1940 and 1941.

As militarists took control of the Japanese government, Japanese policies in the Far East be-came even more aggressive. Japan sought to create what it called the Greater South East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, in which Japanese influence would extend throughout South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific region. The fancy name meant nothing more than the idea of a Japanese economic empire. Japan needed iron, oil, rubber, tin, and other raw ma-terials, and thus needed to control the economic resources of all of Asia in order to feed her appetite for war. As America became increasingly hostile toward Japanese ambitions and began to tighten trade restrictions, the Japanese warlords began to plot a strategy to con-front America. Because the Philippine Islands had become U.S. territory as a result of the Spanish-American War, that American possession due south of Japan lay smack in the middle of Japan’s area of interest. Japanese leaders believed it inevitable that conflict would eventually erupt between the Empire and the United States.

In order to get the upper hand quickly, Japan planned and executed a lightning strike against the Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The plan was agreed upon in late summer 1945, and soon the Japanese fleet was sailing across a remote area of the North Pacific, preparing to attack Pearl Harbor from the northwest. The story of the attack on Pearl Harbor has been told in detail, and assertions that President Roosevelt knew the attack was coming and did nothing about it have been laid to rest. No evidence supports such a claim, although there is substantial evidence that the United States should have been better prepared. In any case the attack came, and while it was a tactical victory, it was one of the worst strategic blunders in military history. Although American battleships and cruisers were badly damaged or destroyed, as luck would have it the aircraft carriers were at sea that day and thus were untouched. Because the aircraft carrier became the dominant naval weapon in the Pacific theater during the Second World War, the fact that the aircraft carriers were saved was a crucial factor in the future conduct of the war.

Pearl Harbor was not so much a battle as a one-sided attack that came with such shock and surprise that those being attacked were scarcely able to defend themselves. The historic controversies surrounding the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor have centered on the issue of who knew who knew about Japanese plans, and when they were revealed. University of Maryland historian Gordon W. Prange, working with associates Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, has covered the first six months of America’s involvement in World War II in considerable detail in four books:

- At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor. The New York Times called Prange’s At Dawn We Slept “impossible to forget.” Prange’s tireless research into the entire saga of Pearl Harbor leaves little doubt as to the validity of his conclusions. Includes photographs.

- Pearl Harbor: The Verdict of History. In this sequel to At Dawn We Slept, Prange goes into considerable detail to examine how the attack came about and whether there really was some sort of conspiracy involving the president to conceal knowledge of the attack in order to thwart the “America First” movement, whose members opposed American entry into the war.

- December 7, 1941: The Day the Japanese Attacked Pearl Harbor. By Donald M. Goldstein, based on the work of Gordon Prange. In this book Goldstein gets into the chronological details of the “date which will live in infamy.”

- Miracle at Midway. Prange’s history of the battle of Midway details the battle that marked the turning point of World War II against Japan. Prange examined both Japanese and American sources, eyewitness accounts, and so on.

What can we conclude about President Franklin Roosevelt and Pearl Harbor? We can certainly say that President Roosevelt knew that Japan was up to no good and that its war against China, which had been going on since 1937, was likely to expand into other parts of East and Southeast Asia. One glance at a map will show that the United States’ Philippine Islands, located squarely in the center of Japan’s sphere of interest (Indonesia, Indochina, and the surrounding regions) were likely to be attacked. It could, therefore, be assumed that any Japanese action would begin first against the Philippines, and General Douglas MacArthur’s preparations were receiving full support from Washington.

Defenses throughout the Pacific, in fact, were being beefed up in anticipation of possible Japanese action. But the charge that FDR knew that the December 7 attack was coming, leveled in part to deflect blame from the commanders on the scene in Hawaii, fails to stand up on many grounds.

First, if a conspiracy had existed to conceal knowledge of an impending Japanese attack, it would have had to involve top military leaders, including Admiral Leahy, FDR’s chief of staff, the secretaries of the army and navy (both Republicans), and other officials of medium to high rank, all of whom would necessarily have been aware of any communications revealing specific Japanese intentions. Second, Franklin Roosevelt loved the navy. He even took vacations on warships and guided Navy ships into waters off his beloved coast of Maine. That he would have deliberately sacrificed lives and ships to make what amounted to a political point is inconsistent with everything we know about Roosevelt.

Furthermore, if FDR had known the attack was coming and wished to allow a surprise attack to go forward, he could still have directed army and navy forces in Hawaii to be placed on high alert in a battle-ready status under secret orders, without revealing to the world that he knew the attack was coming. The surprise attack would still have had the same shock value to the American people, but it could have been far less devastating. Despite all the speculation, it is exceedingly doubtful that Roosevelt actually knew the time and location of the Japanese attack.

Certainly there is substantial evidence that a lot of people ignored warning signs. The Japanese aircraft were picked up and presumed to be B-17s coming in from the States, never mind that they would have been miles off course and going in the wrong direction; a Japanese submarine was spotted off the mouth of Pearl Harbor; a warning telegram went astray; and so on. All of those things amounted to massive failures of communication and intelligence, but they fall far short of creating evidence of a deliberate conspiracy. The United States was surprised, shocked, and embarrassed by Pearl Harbor.

As the Battle of Midway was soon to demonstrate, however, the United States was resilient, resourceful, and more than ready to take up the fight. Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, and Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King, begin organizing America’s military forces for action in coordination with their British counterparts. Marshall’s superb performance throughout the war and after has placed him with Washington and Grant as America’s most important military leaders. He later served as Secretary of State under President Harry Truman and was author of the Marshall Plan.

Coral Sea and Midway: The Tide Turns in the Pacific

The factor that kept the attack on Pearl Harbor from being a total disaster was that the American aircraft carriers were out at sea on December 7 and thus were not damaged. Although the shock and surprise of Pearl Harbor were deeply felt, the United States was not completely unprepared for war. President Roosevelt and Congress had begun beefing up the armed forces as early as 1940, but there was a lot of catching up to do. Both the Germans and Japanese had been fighting for years and were thus experienced in warfare.

Desiring to make at least a symbolic response to Japan for the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, the military command decided to make a daring raid on Tokyo in April 1945. A group of sixteen B-25 bombers were carried aboard the carrier U.S.S. Hornet far into the western Pacific, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle. From there they flew over Japan and bombed Tokyo, Yokohama and three other cities. Most of the planes crash landed in China. Although the damage was minimal, the raid boosted American morale. Most of the air crews made it to safety with the help of the Chinese. Three were captured and Executed by the Japanese and several more were imprisoned until 1945. Colonel Doolittle was awarded the Medal of Honor and promoted to brigadier general.

In May and June of 1942, two great sea battles marked the turning point in the war in the Pacific. On May 7 and 8 the Battle of the Coral Sea was fought, the first naval battle in history in which the surface ships were not within sight of each other and did not participate in the battle directly against the opposing fleets. Although some of the navy aircraft squadrons suffered losses, naval aviators took the fight to the Japanese, sinking one Japanese aircraft carrier and damaging two others along with several other ships.

In May and June of 1942, two great sea battles marked the turning point in the war in the Pacific. On May 7 and 8 the Battle of the Coral Sea was fought, the first naval battle in history in which the surface ships were not within sight of each other and did not participate in the battle directly against the opposing fleets. Although some of the navy aircraft squadrons suffered losses, naval aviators took the fight to the Japanese, sinking one Japanese aircraft carrier and damaging two others along with several other ships.

Although the Americans lost the aircraft carrier Lexington at Coral Sea, the battle prevented the Japanese fleet from continuing its advance into the southern Pacific, by which it had hoped to cut the American supply lines to Australia.

Following Coral Sea the Japanese attempted to seize Midway Island in June 1942, but again the United States Navy rose to the occasion. The Americans suffered heavy losses early in the engagement when they had trouble locating the Japanese carrier force, but they finally caught a glimpse of the Japanese carriers while they were rearming and refueling their planes between strikes. The dive bombers swooped down through the clouds and dealt a crippling blow to the Japanese fleet, sinking four aircraft carriers and destroying 275 planes. (See Gordon W. Prange, Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, Miracle at Midway, London: Penguin Military Classics, 2002.)

The twin defeats at Coral Sea and Midway meant that the Hawaiian Islands remained secure and placed the U.S. Navy in a position where it could begin to carry the battle to the enemy instead of fighting a defensive war. Although Japan’s naval strength caused further extensive damage to the U.S. Navy, Midway was the turning point of the Pacific War.

The Battle for Guadalcanal: The First U.S. Ground Offensive of World War II

Believing that Germany was a greater threat to the future of the West than was Japan, the British and American Joint Staffs adopted a policy of “Germany first” in early 1942. Although Hitler’s armies were already deeply engaged in the Soviet Union, Germany still had powerful armies available in Italy and France for the defense of the Western front. But even as plans were underway for the invasion of North Africa, a dangerous situation arose in the Pacific, and the U.S. had to divert its attention to Japanese action in the South Pacific.

Believing that Germany was a greater threat to the future of the West than was Japan, the British and American Joint Staffs adopted a policy of “Germany first” in early 1942. Although Hitler’s armies were already deeply engaged in the Soviet Union, Germany still had powerful armies available in Italy and France for the defense of the Western front. But even as plans were underway for the invasion of North Africa, a dangerous situation arose in the Pacific, and the U.S. had to divert its attention to Japanese action in the South Pacific.

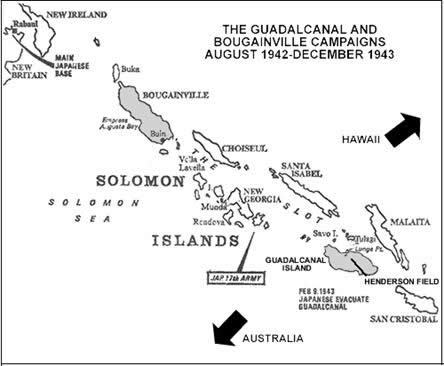

Hawaii would clearly be used as a major staging base for American forces making their way into the South Pacific to attack the Japanese. General MacArthur had evacuated from the Philippines to Australia, which was the obvious best location for the buildup of forces for the campaign against Japan. But along the sea lanes from Hawaii to southern Australia lay the island of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Island chain. In the summer of 1942 American intelligence discovered that the Japanese were preparing an airfield on the Guadalcanal Island from which they could easily attack American shipping en route to Australia.

The island was lightly defended, and the First Marine Division under General A. A. Vandegrift landed on Guadalcanal to hold that vital spot against further Japanese development. In August 1942 the marines went ashore against light resistance, but the Japanese were not willing to give up Guadalcanal without a fight, and Japanese air attacks hindered the landing of equipment and materiel. By August 20 marines had completed construction of the Japanese airfield, renamed Henderson Field, which gave the troops close air support. (Richard Tregaskis, Guadalcanal Diary, now in a Modern Library edition, is a classic of wartime journalism.)

The Japanese fleet, skilled at night warfare, cruised up and down the island chain, wreaking havoc on the American troops ashore with heavy bombardments. They also drove off the American fleet, leaving the marines temporarily short of supplies. Japanese infantry repeatedly attacked the marine positions, and an extensive battle involving the marines and a Japanese division raged during October 1942. Reinforced by units from the Second Marine Division, General Vandegrift expanded the marines’ perimeter, pushing the Japanese out of artillery range of the airfield. The bloody struggle went on until February 1943 when Guadalcanal was finally secured, though the Japanese were able to evacuate 13,000 troops from the island.

The Japanese fleet, skilled at night warfare, cruised up and down the island chain, wreaking havoc on the American troops ashore with heavy bombardments. They also drove off the American fleet, leaving the marines temporarily short of supplies. Japanese infantry repeatedly attacked the marine positions, and an extensive battle involving the marines and a Japanese division raged during October 1942. Reinforced by units from the Second Marine Division, General Vandegrift expanded the marines’ perimeter, pushing the Japanese out of artillery range of the airfield. The bloody struggle went on until February 1943 when Guadalcanal was finally secured, though the Japanese were able to evacuate 13,000 troops from the island.

The fighting on Guadalcanal was a new experience for the marines, who were not as familiar with jungle warfare as their Japanese opponents. They quickly became acquainted with Japanese tactics, their ferocity, their use of stealth in probing and raiding defensive positions, and their grim determination to fight to the death. The battle for Guadalcanal went down in the annals of the Marine Corps’s most famous battles as it became the first stepping stone in the march across the Central Pacific toward the Japanese homelands.

The Central Pacific Drive

The American drive across the Central Pacific against Japan was led by the navy under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, at the center of which were the six marine divisions and additional army units. Once Guadalcanal was secured, planners came up with an idea of leapfrogging across the string of defended Japanese islands, not wanting to use valuable resources to capture every stronghold along the way. Starting with each secured island they drew a circle out to the maximum range of adequate air support for the ground troops and selected a target on the outer rim.

The strategy of “island hopping” had benefits. Once the remote island was secured, any Japanese forces remaining on the intermediate islands had been effectively neutralized. Without air support of their own, there was no way they could impede the Allied advance. The strategy also aided a more rapid advance, because larger areas of the South Pacific were brought more quickly under control. During the advance the United States Navy was waging its own campaign against the Imperial Japanese Navy, fought heavily with carrier aircraft. Meanwhile American and Japanese submarines played their roles in attempting to neutralize the opposing fleets.

That effective island-hopping strategy, however, did not mean that taking the islands themselves was any easier. Although the marines perfected their amphibious techniques further with each landing, the Japanese were well dug in and defended their island strongholds with ferocity.

Bougainville

The next stop for the marines in the Pacific once Guadalcanal was secured was the island of Bougainville at the other end of the Solomons chain. The strip of ocean running down the center of the Solomon Islands was known as “the Slot.” Fleets of Japanese ships called the “Tokyo Express” moved up and down the Slot regularly, threatening American forces on the islands. The capture of Bougainville further neutralized the Japanese fleet and advanced the campaign toward the overall objective of Japan itself.

On November 1, 1943, marines went ashore at Empress Augusta Bay for the landing on the island of Bougainville. The Japanese had 60,000 troops on the southern part of the island who were supported by air and naval forces from Rabaul on New Britain Island. Shortly after the landings, the navy under Admiral Halsey launched an air strike from carriers against Rabaul, relieving the pressure on the American troops. Bougainville was a battle that saw some of the fiercest fighting of World War II, and after the Americans left for their next operations, Australian troops continued to fight Japanese on Bougainville until the war ended.

The Gilberts: Makin and Tarawa

As army forces under General Douglas MacArthur moved along the northern coast of New Guinea, the navy and marines prepared for an assault on the Gilbert Islands to the north of Guadalcanal. Tarawa Atoll itself is a collection of coral islands in a triangular shape roughly 12 by 18 miles. Its location made it a major steppingstone on the drive toward the home island of Japan. Japan had seized the Gilberts in 1941 and had been busily building defenses since that time. The islands of Makin and Betio are also part of the Gilberts.

As army forces under General Douglas MacArthur moved along the northern coast of New Guinea, the navy and marines prepared for an assault on the Gilbert Islands to the north of Guadalcanal. Tarawa Atoll itself is a collection of coral islands in a triangular shape roughly 12 by 18 miles. Its location made it a major steppingstone on the drive toward the home island of Japan. Japan had seized the Gilberts in 1941 and had been busily building defenses since that time. The islands of Makin and Betio are also part of the Gilberts.

Tarawa became one of the bloodiest battles fought by the Marines during the war. The island was very heavily fortified, and several days of naval bombardment failed to dislodge most of the defenders.

The Second Marine Division landed on Betio, the main island of the Tarawa Atoll, on November 22, 1943, after a three-hour bombardment. Betio was a strong fortress of bunkers made from coconut logs and coral cement. It contained the only airfield on the atoll and was defended by well-trained Japanese soldiers. The landing area was protected by intersecting fields of fire. Hampered by coral reefs that required the marines to wade for long distances to get to shore, the first wave of attackers suffered almost 100 percent casualties. Once ashore, marines used flamethrowers to drive defenders out of underground bunkers as they worked their way painfully along the atoll. The final victory at Tarawa followed the repulse of a “Banzai” or suicide attack by the fierce Japanese defenders. Although the Japanese commander had claimed that it would take years for an enemy to capture Tarawa, the American marines accomplished it in seventy-six hours.

Although the fighting in Tarawa lasted only four days, 1,000 Marines were killed and 3,000 wounded. Back in the United States, the government had restricted newsreels in movie theaters, the primary source of visual news in an era preceding television, from showing American casualties. But as the telegrams continued to arrive to the families of fallen fighting men, the restrictions were lifted, and the first newsreels showing American casualties were those from the Battle of Tarawa. The action at Tarawa continued to place pressure on Japanese defenders as the drive through the Southwest Pacific along the New Guinea coast was taking shape, and the Japanese found it increasingly difficult to defend both areas.

The Marshalls: Kwajalein

The assault of the Marshall Islands opened a new phase of the Pacific war, for now the Americans were attacking islands that had been awarded to Japan at the end of the First World War and that they had occupied long before 1941. The target selected for the main assault on the Marshalls was the Kwajalein Atoll, which was in the center of the islands. It was located approximately six hundred miles northwest of Tarawa.

A secondary objective was the Eniwetok Atoll. Knowing that the Japanese defenders had possessed the Marshall Islands for twenty years prior to the start of the war made American planners aware of the fact that the landing would not be easy. Everything they had learned from Guadalcanal and Tarawa would be considered in planning the assault.

In addition to the transports that would carry the troops, aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers also supported the assault with air attacks and naval bombardment prior to the landings. The overall commander of the operation was Major General Holland M. Smith, Commander of the Marine V (Fifth) Amphibious Corps, known within the Marine Corps as “Howlin’ Mad” because of his ferocious temper. The main elements of the assault force would be the Fourth Marine Division and the Seventh Infantry Division of the United States Army.

D-Day for the invasion of the Marshalls was January 31, 1944. Following a heavy pre-landing bombardment, marines and army troops landed on various islands of the Atoll and set up artillery batteries to support the landings on more heavily defended beaches. Because the Kwajalein Atoll is very narrow, the Japanese defended close to the beaches, using strong counterattacks.

After days of fierce fighting, almost all of the Japanese defenders had been killed, and within days of the first invasion marine ground troops had repaired the Japanese airfield for use by marine aircraft. By mid-February the first Japanese “mandated” islands (those awarded to Japan at Versailles) were in American hands.

Next, it was on to Saipan and the Marianas, another step closer to Japan itself. Note: For links to maps of the Pacific Theater visit academicamerican.com/worldwar2.

The Southwest Pacific Drive: Allied Forces Move Toward the Philippines

Of all the quotations attributed to famous military leaders, General Douglas MacArthur’s “I shall return” ranks with the best known. General MacArthur had been the American military commander of forces in the Philippines since 1935 and had grown to love the Islands and the people. In March 1942 President Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to remove himself and take command of operations in the Southwest Pacific area, MacArthur vowed to come back to liberate the Philippines from Japanese control.

Immediately after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, they had turned on the Philippines, and despite heroic resistance by the Americans and the Philippine army, the Islands finally fell in April 1942. MacArthur was evacuated secretly by a patrol torpedo boat and made his famous promise upon his arrival in Australia. Meanwhile the Americans, who had established a final line of defense at Bataan, were forced to surrender to superior Japanese forces. Many prisoners suffered and died during the infamous Bataan death march, and many more spent three gruesome years in Japanese prison camps.

MacArthur’s plans to move back toward the Philippines were hampered by the fact that the American and British staffs in Washington and London were struggling to allocate scarce resources while honoring their joint commitment to conquer Germany first. The attack on Guadalcanal had been necessitated by the threat of the Japanese airfield that was under construction, and the Pacific commanders insisted on keeping the pressure on Japan, a decision that was finally agreed upon by Allied leaders during the Casablanca Conference of January 1943. At that same conference, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill agreed on the policy of “unconditional surrender.”

While the navy and marines under Admirals Nimitz and Halsey and army units under General MacArthur moved through the Solomon and Gilbert Islands, MacArthur’s troops and Australian forces were preparing to advance toward the Philippines along the northern coast of New Guinea. MacArthur had pointed out the advantage of that second route in that it would provide for land-based air cover along the way. The double-pronged advance—the Southwest Pacific route and the Central Pacific drive—had the dual merits of keeping Japanese forces divided and of providing opportunities for surprise.

The advance through New Guinea began in April 1944. MacArthur followed the same general strategy adopted by Halsey and Nimitz in the Central Pacific—leapfrogging over lesser points of resistance to cut them off, leaving them for Australian forces to neutralize. After several initial landings, MacArthur’s troops established a large base at Hollandia in Dutch New Guinea. From there they moved westward up the coast, gradually getting closer to their objective of the Philippines.

As the Japanese moved to reinforce western New Guinea with aircraft from the Marianas, they discovered that the Americans were preparing to attack the Marianas, leaving the Japanese forces stretched very thin. By late July 1944 Allied forces were at the western tip of New Guinea and began planning for the assault on the Philippines, just as the marines and army were capturing Saipan, Tinian, and Guam in the Marianas.

The Mariana and Palau Islands: Saipan, Tinian, Guam, and Peleliu

The Mariana Islands, which include the islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian, lie about 1,200 miles west northwest of Kwajalein and about 1,350 miles south of Tokyo. The decision to attack the Marianas was based upon a desire to keep pressure on the Japanese in the Central Pacific and to create air bases from which bombers could attack Japan directly. With the Marshalls as a base from which to operate, the attack on the Marianas was feasible. The leapfrog strategy was beginning to pay off.

The United States had acquired the island of Guam as a result of the Spanish-American war, but the remainder of the Marianas had been in Germany’s possession until after the First World War, when they were awarded to Japan. One of Japan’s first objectives after the outbreak of World War II was the capture of Guam. The Japanese had also constructed two air bases on the island of Saipan. Because the United States forces had been advancing so rapidly through the Central Pacific, the defenses on Saipan were not as well developed as the Japanese had hoped, though the Japanese had substantial troop concentrations totaling about 29,000 throughout the Marianas.

The United States had acquired the island of Guam as a result of the Spanish-American war, but the remainder of the Marianas had been in Germany’s possession until after the First World War, when they were awarded to Japan. One of Japan’s first objectives after the outbreak of World War II was the capture of Guam. The Japanese had also constructed two air bases on the island of Saipan. Because the United States forces had been advancing so rapidly through the Central Pacific, the defenses on Saipan were not as well developed as the Japanese had hoped, though the Japanese had substantial troop concentrations totaling about 29,000 throughout the Marianas.

A task force of approximately eight hundred vessels was assembled to carry soldiers and marines from bases more than one thousand miles away to the Marianas landings. Both navy and marine planners had continued to refine the techniques of amphibious warfare, and improvements in supporting equipment and landing craft had continued apace. The overall commander of the operation was Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, U.S.N., commander of the Fifth Fleet. Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith was in command of the entire landing force for the attack on the Marianas.

Coordination of the invasion itself was complex, as troops came from as far away as Hawaii. Prior to the invasion, as was done at the previous objectives, naval gunfire and aircraft were used to soften up the defenses of the islands. Saipan was bombed heavily on June 12 and 13, 1944, and naval gunfire operating directly against the shore targets began on the 13th. As had been the case in the past, however, many heavily fortified and well dug in Japanese defensive positions remained intact.

On June 15 and 16, the Second and Fourth Marine Divisions and the 27th Army Division landed on Saipan. With a large number of troops in a relatively confined area, confusion ensued on the beaches as units became mixed up. But the marines were aware of their objectives and advanced resolutely in the face of heavy defensive fire. During the first night ashore the landing force encountered Japanese counterattacks, which were successfully repulsed. On D-Day plus 1 additional troops were landed, and the advance continued relentlessly for more than three weeks until the island of Saipan was secured.

Within a few days after the end of the Saipan operation, the Second and Fourth Marine Divisions moved on the neighboring island of Tinian, which was taken in a matter of approximately two weeks. By the middle of August the island of Guam was also secured. The recapture of Guam, a former possession of the United States, was a high point of the Pacific war.

Once the islands were secured a large air base was prepared from the Japanese base that had existed prior to the American invasion, and B-29 bombers were soon using Saipan as a launch point for raids on the home islands of Japan. On August 6, 1945, the B-29 named the “Enola Gay” took off from Saipan and dropped the first atomic bomb in history on the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

Peleliu

The island of Peleliu in the Palau Islands lies between the Mariana Islands and the Philippines and was initially considered an important objective in the Western Pacific. In retrospect it has been suggested that it might have been well to bypass the Palau Islands, but Admiral Nimitz never canceled the operation, and it went forward.

Initial intelligence suggested that Peleliu would be a relatively easy target, but such was not the case. The terrain on the island consisted of coral ridges in which caves had been dug and reinforced with concrete and other obstacles. Thus the pre-invasion bombardments did little damage to the Japanese defenders.

The First Marine Division landed on September 15, 1944, and the marines found the going extremely tough. Fighting in extreme heat with temperatures well over 100 degrees, Marines found advancing physically troublesome over the sharp coral, which could even cut through boots. Marines had captured the airfield that was the main objective by September 30, but many Japanese were still on the island and the fighting continued into November. The assault on Peleliu cost more than 1,000 killed and 5,000 wounded. The job of the Americans was made slightly easier because the Japanese were beefing up defenses in the Philippines and the Ryukus (Okinawa); nevertheless, the fighting on Peleliu was some of the most brutal of the war.

MacArthur Returns to the Philippines

As American forces began to move near the Philippines in late 1944, Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet conducted a lengthy battle against Japanese carrier- and shore-based aircraft. But the Japanese Navy, which had suffered continuous losses since the battles of Coral Sea and Midway, was not the same navy and naval air force that had attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. Japanese losses during this phase of fighting were more than five hundred aircraft, considerable shipping, and damaged base facilities. Japanese reporting on the battle, however, was wildly exaggerated, leaving Japanese commanders in the Philippines to think it was American naval and air power that had been severely damaged. In fact, the opposite was true.

As American forces began to move near the Philippines in late 1944, Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet conducted a lengthy battle against Japanese carrier- and shore-based aircraft. But the Japanese Navy, which had suffered continuous losses since the battles of Coral Sea and Midway, was not the same navy and naval air force that had attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. Japanese losses during this phase of fighting were more than five hundred aircraft, considerable shipping, and damaged base facilities. Japanese reporting on the battle, however, was wildly exaggerated, leaving Japanese commanders in the Philippines to think it was American naval and air power that had been severely damaged. In fact, the opposite was true.

When the force assembled at Hollandia in October 1944 for the invasion of Leyte Island, the initial objective in the Philippines, it was one of the most powerful naval and military assemblies in history. The Allied force consisted of more than 700 ships and 160,000 troops, including battleships, cruisers, escort carriers, and destroyers, as well as the amphibious assault vessels.

On October 20, 1944, the assault force approached the Philippines through Leyte Gulf. The VII Amphibious force began its landings at 10 o’clock, and at one that afternoon General MacArthur left the U.S.S. Nashville to go ashore, wading through the surf with his staff in their freshly pressed khaki uniforms. Although fighting raged nearby, General MacArthur ignored it and announced over the radio: “People of the Philippines, I have returned! By the grace of Almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil.” Two days later General MacArthur and Philippine President Osmeña announced that civilian government had been restored to the Philippines. MacArthur had fulfilled his promise.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf: Beginning of the End

Meanwhile, as the American forces in the Philippines expanded from their initial beachhead, a Japanese fleet under Admiral Kurita was heading for the island of Leyte. For three days, October 23–26, 1944, what remained of the Imperial Japanese fleet engaged the American fleet under Admiral Halsey in the Battle of Leyte Gulf. During the action the Japanese lost four aircraft carriers, three battleships, ten cruisers, eleven destroyers, and one submarine, and virtually every Japanese ship engaged in the battle was damaged. The Japanese also lost 500 aircraft and 10,000 sailors and airmen. As the Allies consolidated their positions in the Philippines, the Japanese navy retreated northward in the direction of Japan in preparation for the assault on Okinawa in the Ryukyu Islands, which would be the last step before the Allies were in a position to invade Japan itself.

Fighting continued in the Philippines throughout 1945. In early January, General MacArthur’s forces on Leyte approached the main Philippine Island of Luzon. In a series of landings American troops went ashore and closed in on Manila Bay and the capital city. In late February, as the Americans were closing in, the Japanese commander ordered a fierce suicidal defense that resulted in the destruction of many buildings in the city of Manila. By the time the American army had driven all the Japanese out, more than sixteen thousand Japanese soldiers had been killed. Although the Americans now controlled the Philippine Islands, various strong points remained in Japanese hands until the end of the war in August 1945.

Battle of the Philippine Sea: “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”

The irreverent name given to the Battle of the Philippine Sea in the Marianas reflects the fact that by the end of the battle in June 1944, Japanese naval air power had been virtually neutralized. It was a process that had begun at Midway in 1942. Japanese losses throughout the Pacific campaign had been growing greater ever since the latter days of the Guadalcanal campaign.

By the spring of 1944 Japan had rebuilt its navy with newly trained pilots and felt prepared to embark upon an operation designed to regain the balance of power vis-à-vis the American navy. Japanese Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, in command of six aircraft carriers, five battleships, seven heavy cruisers, in addition to destroyers and support vessels, headed for the Marianas.

By the spring of 1944 Japan had rebuilt its navy with newly trained pilots and felt prepared to embark upon an operation designed to regain the balance of power vis-à-vis the American navy. Japanese Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, in command of six aircraft carriers, five battleships, seven heavy cruisers, in addition to destroyers and support vessels, headed for the Marianas.

Ozawa had certain advantages over the Americans, including the fact that his aircraft had a much greater range than those of the U.S. Navy. Since Admiral Spruance’s naval forces had the primary mission of protecting the American troops on Saipan, Spruance was limited in his ability to maneuver to intercept Ozawa. The inexperience of the Japanese combat pilots, however, more than offset Spruance’s limitations.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea took place on June 19–21, 1944, and June 19 became a memorable date in U.S. naval history. Admiral Ozawa was planning to get assistance from land-based aircraft on the island of Guam, still under Japanese control. On the morning of June 19 his carrier-based aircraft were launched for their first mission against the U.S. fleet. By about 10 o'clock on June 19, U.S. Navy radar located the Japanese fleet and launched interceptor aircraft. As the Japanese warplanes approached the American fleet for their attack, the Americans pounced on them and immediately destroyed more than fifty aircraft. None of the attacking Japanese planes ever reached the American aircraft carriers, their primary objective.

While the air battle was going on, two United States submarines, the Albacore and the Cavalla, sank two of the Japanese aircraft carriers, the Taiho and Shokaku. The Taiho had been the largest and newest Japanese aircraft carrier.

The second Japanese air raid involved 130 Japanese airplanes, and the American defenders shot down 98 of them. About twenty Japanese planes got through and closed on the American battle fleet, but most were destroyed by antiaircraft fire from destroyers and battleships. A third raid resulted in no Japanese losses as the pilots failed to locate the American fleet. Later that morning the Japanese launched a fourth large raid consisting of 82 aircraft, but only nine of them survived. Meanwhile U.S. naval aircraft attacked Japanese facilities on Guam.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea was the largest aircraft carrier battle of the World War II and was significantly larger than the Battle of Midway. In the “Great Marianas turkey shoot,” Admiral Ozawa’s forces lost 346 aircraft and two aircraft carriers; 30 American planes were shot down and one battleship was struck by a bomb that did minor damage.

The first four raids of the battle occurred on the first day, and thereafter the American navy was in pursuit of the Japanese. In the ensuing fights the Japanese lost 65 more aircraft that had survived from the first day's fighting. By June 22, when the Japanese fleet retreated to the anchorage in Okinawa, they had only 35 aircraft left out of the 430 they had at the onset of the assault on the American navy. Three aircraft carriers had been sunk and, most important, more than 400 new aviators had been lost and could not be replaced in time for the next battle, which was that of Leyte Gulf.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea solidified the Allied hold on the Marianas Islands. Once Saipan was secured, Marines quickly captured Guam and Tinian. The 77th Infantry Division of the United States Army also participated in the invasion of Guam. Those terrible losses of the Marianas and a major portion of the Japanese navy led to the resignation of General Tojo and his cabinet on July 18, 1944. Although the invasions of the Philippines, Okinawa, and the home islands of Japan lay ahead, it was clear that the momentum was overwhelmingly on the side of the Allies.

The Capture of Iwo Jima: “Uncommon Valor was a Common Virtue.”

Not long ago the film Flags of our Fathers, about the battle of Iwo Jima, was released. A Japanese film about the same battle soon followed. Because of the famous photograph by Joe Rosenthal of the flag raising on Mount Suribachi and the corresponding statue by Felix de Weldon that overlooks the Memorial Bridge and the District of Columbia, Iwo Jima is one of the most famous battles of World War II and probably the most famous battle fought in the Asian theater.

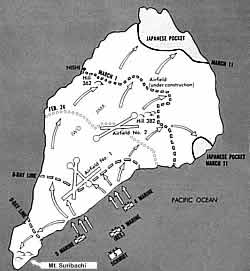

The fame is well deserved, for it is clear that Iwo Jima was one of the toughest battles fought by the Marines in World War II. The small island of Iwo Jima lies about six hundred miles south of Tokyo. The island is mostly flat. But at its southern tip Mount Suribachi, an extinct volcano, rises more than five hundred feet ,from which the entire island and its beaches can be observed. For that reason, it was a particularly difficult island to capture.

The fame is well deserved, for it is clear that Iwo Jima was one of the toughest battles fought by the Marines in World War II. The small island of Iwo Jima lies about six hundred miles south of Tokyo. The island is mostly flat. But at its southern tip Mount Suribachi, an extinct volcano, rises more than five hundred feet ,from which the entire island and its beaches can be observed. For that reason, it was a particularly difficult island to capture.

By February 1945, Iwo Jima was one of the chief Japanese defensive strongholds that had not yet been captured. Its capture was designed to help bring the Pacific war to a successful conclusion. Most important, the Bonin Islands, of which Iwo Jima was a part, lay directly between Saipan and Tokyo. The planned attack on Iwo Jima had four objectives:

- To provide fighter cover for bombing missions against Japan

- To deny this strategic outpost to the enemy

- To create defensive airbases to protect positions in the Marianas

- To provide air fields for staging heavy bomber raids against Japan

Prior to the landing on Iwo Jima, the navy conducted the longest and most intensive bombardment given any ground objective during the Pacific war. Starting with air strikes in 1944, which may have driven the Japanese defenders deeper underground, the blasting of the island continued through the morning of February 19, 1945.

The Japanese commander on Iwo Jima recognized that the volcanic soil on the island could be mixed with cement to form a very strong concrete. The Japanese had more than 21,000 men on the island and about 500 heavy weapons, all of which were positioned in reinforced concrete bunkers and caves. Because Iwo Jima was actual Japanese territory, the American commanders knew that it would be defended as fiercely as anything they had previously encountered.

The marine units in the invasion of Iwo Jima were the V Amphibious Corps, which consisted of the Third, Fourth and Fifth Marine Divisions. Navy ships, including five battleships, bombarded the island of Iwo Jima heavily for three days before the landings began. Nevertheless, it became clear once the marines were ashore that many of the defenses had been untouched. Because the Japanese defenders had dug so deeply into the earth, the bombardments had not damaged them.

On the morning of February 19, 1945, an additional heavy bombardment commenced in advance of the landings, which began at around 8:30. As the troops went ashore they immediately encountered soft volcanic ash, which made advancing very tedious. But because the bombardments had neutralized the defenses close to the beaches the initial assault was not heavily defended. The farther the marines got inland, the more deadly the defensive fires became. Japanese mortar and artillery fire rained shells on the beach, causing casualties even among men who were already wounded and who had been evacuated back to the beach.

Despite those difficulties the marines landed 30,000 men on the first day of the invasion. Mount Suribachi, the lonely height on the southern end of the island of Iwo Jima, was the objective of the 28th Marine Regiment. Japanese observers on the top of the mountain were using their advantageous position to direct artillery onto the marine invaders. On the second day of the assault, the 28th Marines attacked the mountain, which was covered with defensive bunkers, machine gun pillbox positions, and caves. After three days of difficult fighting, the marines finally reached the top of the mountain and raised a small flag.

The photographer who took the picture of the first flag raising had his camera knocked out of his hand and destroyed by a grenade, but he saved the film. As he was heading down the mountain looking for another camera, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal arrived and discovered that the marines were about to raise a larger flag that could be seen all over the island and by the offshore ships. Rosenthal snapped the picture of the second flag raising, and it became one of the most famous photographs of war ever taken and the model for the bronze statue that stands near Arlington Cemetery just outside Washington. Stories that the second flag raising was staged were put to rest long ago. Rosenthal was lucky to be in the right place at the right time. (The official U.S. Marine Corps history of the Iwo Jima campaign confirms that the second flag raising was not staged.)

The photographer who took the picture of the first flag raising had his camera knocked out of his hand and destroyed by a grenade, but he saved the film. As he was heading down the mountain looking for another camera, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal arrived and discovered that the marines were about to raise a larger flag that could be seen all over the island and by the offshore ships. Rosenthal snapped the picture of the second flag raising, and it became one of the most famous photographs of war ever taken and the model for the bronze statue that stands near Arlington Cemetery just outside Washington. Stories that the second flag raising was staged were put to rest long ago. Rosenthal was lucky to be in the right place at the right time. (The official U.S. Marine Corps history of the Iwo Jima campaign confirms that the second flag raising was not staged.)

Those unfamiliar with the history of Iwo Jima are inclined to believe that the flag raising was the culmination of a battle, but it was only the beginning. In the three weeks of fighting to take the island, almost 7,000 marines were killed and almost 20,000 were wounded: a majority of those casualties occurred after the marines raised the flag on Mount Suribachi. Almost all of the 21,000 Japanese defenders were killed in the battle.

One of the main objectives of taking Iwo Jima had been to capture the airstrips. Engineers and navy Seabees began working on the airfields even before the island was fully secured. But soon after the fighting ended the airfield on Iwo became operational as an emergency landing strip. B-29 bombers that had been flying from Saipan to bomb the home islands of Japan could now land there. By the time the war was over, more than 2,400 emergency landings had taken place on Iwo Jima and many fliers’ lives had thus been saved.

When the fighting on Iwo Jima was over, Admiral Nimitz wrote, “Among the Americans who served on Iwo island uncommon valor was a common virtue.” When considering that the island of Iwo Jima is only 7½ square miles in size, it is clear that a great deal of heroism occurred in a very small place.

During the Battle for Iwo Jima Marine Corps Navajo code talkers used their skills to help ensure success of the operation. The Marines had begun recruiting and training Navajo Indians in 1942. The code they used was based on the Navajo language—the code talkers could encode and transmit secret messages by radio faster than any mechanical coding device. Following Iwo Jima a Marine communications officer stated, "Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima." Six Navajo code talkers on Iwo sent and received over 800 messages during the battle, all without error. Some 400 Navajos served as code talkers with the Marines during the war.

The Battle for Okinawa

The battle for Okinawa was the largest battle in the Pacific in World War II, and the landings on the island were supported by the most powerful fleet ever assembled. The invasion of Okinawa was set for April 1, 1945, and pre-invasion bombings from Saipan had been going on for weeks.

The battle for Okinawa was the largest battle in the Pacific in World War II, and the landings on the island were supported by the most powerful fleet ever assembled. The invasion of Okinawa was set for April 1, 1945, and pre-invasion bombings from Saipan had been going on for weeks.

The island of Okinawa itself is larger than many of the islands that had previously been attacked. It is shaped something like a large combination banana and hourglass, with thick, uninhabited tropical jungle in the northern half and a heavily populated built-up area in the south. At the center of the populated south is the capital city of Naha, which lies below a mountain topped by Shuri Castle. The population of Okinawa in 1945 was approximately half a million Okinawan natives, mostly civilians, who, although Okinawa was part of Japan, are a separate race from the Japanese.

Given the size of the island the invasion force was large, consisting of three marine divisions and four U.S. Army infantry divisions with a fifth U.S. infantry division in reserve, in all approximately 300,000 combat and support troops. Marine Lieutenant General Roy Geiger and Army Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner, who commanded the army divisions, were both experienced combat commanders and got along quite well, in contrast to the friction that had occurred during some previous army and marine joint operations.

The supporting fleet for the battle of Okinawa consisted of forty large and small aircraft carriers, eighteen battleships, and hundreds of destroyers and cruisers.

There were several airfields on the island, and the Americans anticipated that they would be fiercely defended by the 100,000 troops in the Okinawa garrison. The Japanese plan was to let the Americans get ashore and then lure them into situations in which they could not be well supported by naval gunfire. The low mountains and gullies, in which natural and artificial caves had been prepared for defensive positions and headquarters, made such a plan practical. The Japanese had also learned the lesson that defending against landings in close proximity to the beach areas was extremely costly.

The initial landings near the center of the island were virtually unopposed, and by the evening of the first day 50,000 troops were safely ashore. During the first few days of the invasion, the resistance remained light. Within a matter of hours, Americans had captured two of the airfields at Yonton and Kadena. But by the end of the first week, the Army troops ran into fierce resistance north of the city of  Naha. For days the American soldiers and marines hammered at the heart of the Japanese defenses. Fierce Japanese counterattacks were repulsed with heavy casualties among the Japanese, but the defenses around the Shuri Castle mountain remained extremely strong.

Naha. For days the American soldiers and marines hammered at the heart of the Japanese defenses. Fierce Japanese counterattacks were repulsed with heavy casualties among the Japanese, but the defenses around the Shuri Castle mountain remained extremely strong.

While the fighting went on ashore, the navy had to deal with the latest wave of Japanese defensive tactics, that of the fanatical kamikaze aircraft. Hundreds of kamikaze pilots flew their planes directly into the American ships, causing heavy casualties, especially among the ring of destroyers on picket duty around the invasion force. In addition to the kamikaze attacks the Japanese sent the giant battleship Yamato against the Americans in a desperate attempt to protect the island, which lay only a few hundred miles from Japan.

The fighting on land continued throughout May and into the middle of June until the army and marines finally secured the islands. By the 21st of June 7,000 U.S. soldiers and marines had been killed, including General Buckner. Five thousand sailors died in the kamikaze attacks and thousands more were wounded. On the islands 70,000 Japanese soldiers had died as well as 80,000 Okinawan civilians. An entire Japanese army had been destroyed and hundreds of planes and the battleship Yamato had been sunk. There was little sense of relief for Americansbecause the battle had been one of the most costly of the war on both sides.

Now that Okinawa and the Philippines had been secured, the Central Pacific forces under Admiral Nimitz and the Southwest Pacific forces under General MacArthur were converging on a joint objective: the invasion of Japan. Tensions would grow between army and navy staffs, both of which had developed their own strategic, tactical, and supply methods during the course of the war. With guidance from the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, however, the staffs of Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur began to plan for an invasion of Japan.

Meanwhile B-29 bombers from the island of Saipan continued to rain destruction on the Japanese homeland. Although the Japanese still had an army of hundreds of thousands on the Chinese mainland, their navy had been reduced to the point that even moving soldiers back to Japan would have been extremely difficult. Although the invasion of Japan never actually took place, the initial assaults on the southern island of Kyushu would have involved more 700,000 men, and casualties were expected to be in excess of 200,000.

Meanwhile B-29 bombers from the island of Saipan continued to rain destruction on the Japanese homeland. Although the Japanese still had an army of hundreds of thousands on the Chinese mainland, their navy had been reduced to the point that even moving soldiers back to Japan would have been extremely difficult. Although the invasion of Japan never actually took place, the initial assaults on the southern island of Kyushu would have involved more 700,000 men, and casualties were expected to be in excess of 200,000.

The first operation against Japan was scheduled for November 1945, and the main invasion of the large island of Honshu was scheduled for February or March 1946. The two operations combined would have involved more than one million men. The Japanese were prepared to defend their homeland by all means available, including the employment of “all able-bodied Japanese regardless of sex.” Every Japanese citizen was commanded to be prepared to sacrifice his or her life in suicide attacks against the invaders, and explosives such as Molotov cocktails and other improvised weapons were being prepared.

But as the invasion of Okinawa was being wrapped up, final preparations were underway in Alamogordo, New Mexico, for the testing of the first atomic bomb. The B-29, pictured at the left, was one of the largest aircraft used in World War II. It could fly at 40,000 feet at 350 miles per hour. The most famous aircraft of World War was the B-29 Enola Gay, that plane that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

As part of the debate over whether or not President Truman should have dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, estimates of the possible costs of the invasion of Japan. The Japanese government fully intended to employ as many of its citizens of all ages who were capable of fighting as possible in preparation for the feared invasion. Training of young boys, young men and women was organized. As Japan was running short of Kamekazi aircraft and pilots, young men were being trained as human torpedoes. They would take tiny submarines full of explosives under the Allied landing ships and set them off. Since the entire United States fleet was in Asian waters, the preinvasion and bombardments by dozens of battleships, heavy cruisers and destroyers would have wreaked havoc on Japanese defenses, not to mention further bombings by B-17 and B-29 bombers as well as naval aircraft.

Estimates as to the total number of casualties on both sides have ranged as high as one million. Whether or not that figure is accurate, of course, is beside the point. The invasion would be costly, there was no question of that, and dropping the bombs rendered that planned final attack unnecessary. V-J Day had arrived.

| World War II Home | European War | The Air War over Germany & Japan | Updated April 2, 2020 |