The Manhattan Project: Dawn of the Atomic Age

Copyright © Henry J. Sage, 2012, 2017

In 1939 scientist Leo Szilard approached Albert Einstein with disturbing news. Szilard had heard from scientists in Europe that Germany might be attempting to build a powerful bomb from the element uranium. Szilard wanted Einstein to urge President Roosevelt to initiate research into the matter. After reviewing several drafts with the cooperation of fellow scientist Enrico Fermi, Einstein sent a letter to Franklin Roosevelt in which he described the possibilities that might result from the unleashing of atomic energy. He noted that Germany might already be engaged in such a project and suggested that the president appoint administration officials to consider increasing America’s supply of uranium, the critical ingredient for the construction of an atomic weapon. The President appointed a “Uranium Committee,” but it was provided with only limited resources. As the Germans gained victories in Europe, however, and as it became ever more likely that the United States would become involved in the war, the possibility of developing an atomic weapon became more urgent.

President Harry Truman, who became president upon FDR’s death in April 1945, was unaware of the Manhattan Project at the time of his accession, having been left in the dark by President Roosevelt. Shortly after Truman was sworn in, Secretary of War Henry Stimson approached him with details of the ongoing  project. He described the work on a weapon of terrible destructive power, which had not yet been tested. While the President, along with Secretary Stimson and other top advisors, was attending a conference at Potsdam, Germany, in July 1945 where he met with Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill, he received word that the A-bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico. (Stalin, who already knew of the project thanks to Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, was not surprised when Truman gave him the news.) Truman then sent a message to the Japanese demanding that they surrender or face untold death and destruction. The Japanese never responded to the message, so Truman authorized the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

project. He described the work on a weapon of terrible destructive power, which had not yet been tested. While the President, along with Secretary Stimson and other top advisors, was attending a conference at Potsdam, Germany, in July 1945 where he met with Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill, he received word that the A-bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico. (Stalin, who already knew of the project thanks to Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, was not surprised when Truman gave him the news.) Truman then sent a message to the Japanese demanding that they surrender or face untold death and destruction. The Japanese never responded to the message, so Truman authorized the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

President Harry Truman, who became president upon FDR’s death in April 1945, was unaware of the Manhattan Project at the time of his accession, having been left in the dark by President Roosevelt. Shortly after Truman was sworn in, Secretary of War Stimson approached him with details of the ongoing project. He described the work on a weapon of terrible destructive power, which had not yet been tested. While the President, along with Secretary Stimson and other top advisors, was attending the conference at Potsdam, Germany, in July 1945 where he met with Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill, he received word that the A-bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico. (Stalin, who already knew of the project thanks to Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, was not surprised when Truman gave him the news.) Truman then sent a message to the Japanese demanding that they surrender or face untold death and destruction. The Japanese never responded to the message, so Truman authorized the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. President Truman’s decision has been criticized in hindsight, but the decision never seemed to trouble him, even years after. The president had been advised that an invasion of the Japanese homeland, which was scheduled to begin in November 1945, would cost thousands of American and Japanese casualties.

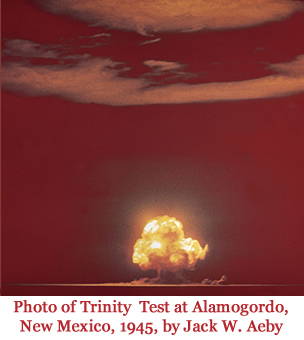

The atomic bomb promised to bring an end to the fighting immediately. After debate among his advisers and objections from some of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project, President Truman decided to go ahead with the attack. On July 25 the decision was made to order the dropping of atomic bombs on selected Japanese cities. Secretary Stimson and General Marshall sent the order to drop the bombs to Army Air Force’s special air group on Saipan. Physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (left) had managed the Manhattan project since 1943 and had overseen the successful Trinity test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, in July.

The first atomic weapon was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Authorization for further attacks was included in the initial directive. The Hiroshima explosion cut off all communication from the city. It was only after a special air reconnaissance from Tokyo had returned from Hiroshima that officials in Tokyo were aware of the damage. Japanese authorities did not meet until August 8 to discuss a response, and opinion was divided. Some Japanese officers doubted that another bomb existed and argued that Japan should fight on. On August 9 the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and launched an attack on Manchuria. Later that day the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

The first atomic weapon was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Authorization for further attacks was included in the initial directive. The Hiroshima explosion cut off all communication from the city. It was only after a special air reconnaissance from Tokyo had returned from Hiroshima that officials in Tokyo were aware of the damage. Japanese authorities did not meet until August 8 to discuss a response, and opinion was divided. Some Japanese officers doubted that another bomb existed and argued that Japan should fight on. On August 9 the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and launched an attack on Manchuria. Later that day the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

Refusing to admit defeat, the Japanese generals argued for a fight to the death, and an attempted military coup was narrowly averted. But within hours of the Nagasaki attack, Japanese Emperor Hirohito, refusing to accept any further destruction of his land and his people, decided to surrender. Despite a last minute rebellion by some generals, the emperor broadcast his decision to the Japanese people on August 14. The long and bloody conflict was finally over.

President Truman’s decision has been criticized in hindsight, but the decision never seemed to trouble him, even years after. The president had been advised that an invasion of the Japanese homeland, which was scheduled to begin in November 1945, would cost thousands of American and Japanese casualties.

The Manhattan Project was officially launched in August 1942. Work on the project took place at 30 sites in the United States and in Great Britain. Production of usable uranium was carried out in the states of Tennessee and Washington, but the main work on the actual construction of a bomb was conducted at Los  Alamos, New Mexico, under the leadership of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Under a cloak of the heaviest secrecy, Oppenheimer assembled a team of brilliant scientists and engineers to tackle the many problems of making an atomic bomb. Few people outside the project were aware of the work, and even those working at different locations were not privy to information about the ultimate purpose of their work. By the time Germany capitulated in May, 1945, Oppenheimer’s team was confident about producing a bomb that could be used in the war against Japan. The bomb was successfully tested on July 16, 1945, at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

Alamos, New Mexico, under the leadership of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Under a cloak of the heaviest secrecy, Oppenheimer assembled a team of brilliant scientists and engineers to tackle the many problems of making an atomic bomb. Few people outside the project were aware of the work, and even those working at different locations were not privy to information about the ultimate purpose of their work. By the time Germany capitulated in May, 1945, Oppenheimer’s team was confident about producing a bomb that could be used in the war against Japan. The bomb was successfully tested on July 16, 1945, at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

President Harry Truman, who had become president upon FDR’s death in April 1945, was attending a meeting at Potsdam, Germany, with Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill when he received word that the A-bomb test had been successful. (Stalin, who already knew of the project thanks to Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, was not surprised when Truman gave him the news.) Truman then sent a message to the Japanese demanding that they surrender or face untold death and destruction. The Japanese never responded to the message, so Truman ordered the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Truman’s decision has been criticized in hindsight, but the decision never seemed to trouble him, even years after. The president had been advised that an invasion of the Japanese homeland, which was scheduled to begin in November 1945 and be followed up in February 1946, would cost thousands of American and Japanese casualties. The atomic bomb promised to bring a swift end to the fighting, as indeed it did. After debate among his advisers and objections from some of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project, President Truman decided to go ahead with the attack, and the first atomic weapon was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, by the B-29 bomber named Enola Gay. The Japanese, in shock, were unable to respond, and a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki a few days later. Japanese Emperor Hirohito, refusing to accept any further destruction of his homeland and his people, ordered the military to end the war, and thus the long and bloody conflict finally ended in August 1945.

An excellent film about the last days of the war, viewed from both the American and Japanese side, is Hiroshima, directed by Roger Spottiswoode and Koreyoshi Kurahara, a joint production of Canada and Japan.

Fears of radiation pollution of the atmosphere finally led to a cessation of nuclear testing. (Raising concerns over the development of nuclear weapons in countries such as Iran and North Korea have raised concerns as well, although no above-ground testing has occurred in recent years.) In addition to state sponsored nuclear weapons programs, concerns exist about the possibility of a terrorist organization not necessarily under the government of an existing state have also raised concerns. Upgrading of older nuclear bombs and missiles is necessary as a matter of course because they are subject to deteriorationAtomic or nuclear power can be used, of course, for civilian as well as military purposes. Nuclear power plants up and functioning in the United States for some time, as well as in other countries. When constructed with safety features in mind, nuclear power plants such as the one pictured on the leftcan operate without doing the same kinds of damage to the environment caused by fossil fuels. On the other hand, health kinds such as the one that happened in Chernobyl in Russia or Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, have led to a halt the construction of new nuclear power facilities. Movies such as "The China Syndrome" heightened public concerns about the dangers of nuclear power. Whether a nuclear power generator can be constructed a small his glove size to power an interplanetary spaceship remains to be seen, the research into the uses of nuclear power will no doubt continue despite reservations.

Fears of radiation pollution of the atmosphere finally led to a cessation of nuclear testing. (Raising concerns over the development of nuclear weapons in countries such as Iran and North Korea have raised concerns as well, although no above-ground testing has occurred in recent years.) In addition to state sponsored nuclear weapons programs, concerns exist about the possibility of a terrorist organization not necessarily under the government of an existing state have also raised concerns. Upgrading of older nuclear bombs and missiles is necessary as a matter of course because they are subject to deteriorationAtomic or nuclear power can be used, of course, for civilian as well as military purposes. Nuclear power plants up and functioning in the United States for some time, as well as in other countries. When constructed with safety features in mind, nuclear power plants such as the one pictured on the leftcan operate without doing the same kinds of damage to the environment caused by fossil fuels. On the other hand, health kinds such as the one that happened in Chernobyl in Russia or Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, have led to a halt the construction of new nuclear power facilities. Movies such as "The China Syndrome" heightened public concerns about the dangers of nuclear power. Whether a nuclear power generator can be constructed a small his glove size to power an interplanetary spaceship remains to be seen, the research into the uses of nuclear power will no doubt continue despite reservations.

| World War II Home | Updated April 30, 2017 |