America and World War I

USMC Memorial in France |

“Over There”—by George M. Cohan “Over there, over there, |

|

America is Drawn into the Conflict over Neutral Rights

When war broke out in August, 1914, consistent with the traditional national mood about such things, President Wilson quickly issued a proclamation of neutrality. He called for Americans to be neutral not only in their actions, but also in their thoughts, a very difficult task, given that about one-third of all Americans had very close ties to the Old World. As news from the warring nations reached this country, however, Americans found it difficult to ignore the reports of atrocities, the massive slaughters on the battlefields, the terrifying new weapons and the huge personal and social costs of the conflict of a magnitude never before seen. Both sides—the Allies, Great Britain and France; and the Central Powers, Germany and Austria—began economic warfare that soon affected the United States. Before long American cargoes were being captured, merchant ships diverted, and many of the older practices of war that had drawn us into the conflict in 1812 against Great Britain arose once more.

The American Civil War had seen advances in weaponry that began to redefine methods of ground combat; but the technology that affected the battlefields by the time World War I broke out was of a very different order of magnitude. Machine guns, barbed wire, poison gas, mechanized vehicles, long-range artillery, tanks, and aircraft were just some of the implements of war that transformed the battlefield. But the weapon that most directly affected America's entry into the war was “undersea boat” (U Boat) or submarine. Fragile and not very maneuverable, submarines on the surface of the water were almost defenseless even against armed merchant ships since they could easily be rammed and sunk. Thus the tactics which evolved called for submarines to shoot first and ask questions later; the traditional practice of firing warning shots and threatening the neutral vessel with a boarding party was no longer viable. Soon many ships were sunk, and civilian passengers were lost, including a number of Americans.

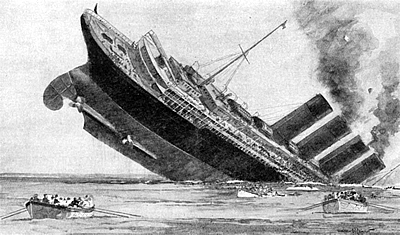

The most famous sinking was that of H.M.S. Lusitania in May 1915. The Germans had placed notices in American newspapers warning civilians to stay clear of the German declared war zone the Germans around the British Isles. When the Lusitania sailed she was outwardly a passenger ship, but her hold contained a large cargo of ammunition bound for Great Britain. The great ship was spotted off the Irish coast by a German submarine, and a single torpedo sent the Lusitania the bottom in 18 minutes. Over 1,100 passengers perished, including 114 Americans. Although many were outraged for humanitarian reasons, the United States did not immediately decide to go to war, as the ship was carrying military supplies.

The most famous sinking was that of H.M.S. Lusitania in May 1915. The Germans had placed notices in American newspapers warning civilians to stay clear of the German declared war zone the Germans around the British Isles. When the Lusitania sailed she was outwardly a passenger ship, but her hold contained a large cargo of ammunition bound for Great Britain. The great ship was spotted off the Irish coast by a German submarine, and a single torpedo sent the Lusitania the bottom in 18 minutes. Over 1,100 passengers perished, including 114 Americans. Although many were outraged for humanitarian reasons, the United States did not immediately decide to go to war, as the ship was carrying military supplies.

Soon after the Lusitania disaster President Wilson called upon the Germans to cease unrestricted submarine warfare; he insisted that they desist from sinking without warning ships which might be carrying neutral civilian passengers. In August 1915 the Germans sunk the Arabic, another British liner, and two more Americans were killed. The Germans, not wanting to draw America into the war, finally consented to issue warnings to civilian vessels, allowing passengers to be saved. In 1916, however, the Germans violated that pledge, sinking the French passenger ferry Sussex and causing 40 civilian deaths (none American), and President Wilson declared that a further violation would cause the United States to sever diplomatic relations with Germany, an act generally considered a prelude to war. The Germans thereupon issued the “Sussex pledge” not to continue the practice of unrestricted submarine warfare.

Looking back from our perspective beyond the history of Nazi Germany, it is hard for Americans today to imagine that early in the last century we might well have gone to war on the side of Germany against England and France, countries we now consider longtime friends. Yet in the early days of the war, British handling of neutral rights also angered the Americans, just as it had under the tenure of President Madison before the War of 1812. In addition, the background issues of World War I were little known to most Americans. Dealing with a huge influx of immigrants, ongoing industrialization, labor disputes and the great reform movement of the Progressive Era, Americans were little interested in foreign affairs, even after the successful Spanish-American War. When World War I broke out in 1914, the attitude of the typical American was probably something on the order of, “There they go again!”—although Europe had been relatively peaceful for the previous century.

This situation prevailed until after the election of 1916. Prior to that election Woodrow Wilson had pursued his progressive goals and had become an effective leader in domestic issues. In foreign policy, as has been seen in his actions regarding Mexico and South America, he was something of an idealist, and certainly an interventionist. Nevertheless, his lofty attitudes toward the European conflict seemed to sit well with Americans, and in the election campaign of 1916 the slogan that brought Wilson victory was, “He kept us out of war.” While that was technically true, Wilson himself knew that the Germans could draw us into war at any time, which they did.

Summary of the Conflict prior to American Entry

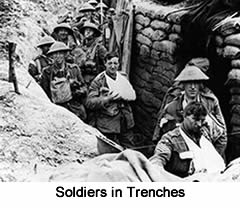

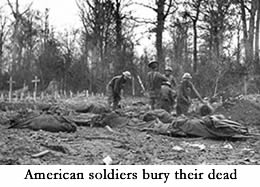

World War I was by many measures the worst war in the history of the world. It certainly was the worst for the fighting men, who for four long years existed in unthinkable conditions of deprivation, fear, discomfort and death. Millions of men lived in trenches and holes in the ground. They had few opportunities to spend the night in untroubled sleep, in a clean bed, with normal sanitary facilities and decent food. The fighting itself, rather than being long periods of boredom interspersed with short bursts of terror, was more like long periods of intermittent fear interwoven with sustained periods of unspeakable violence. Millions of men died horrible deaths, and many millions of others were wounded physically, mentally and spiritually to depths from which it was almost impossible to recover. Casualties in a single day of fighting often rose to the tens of thousands.

The French, on whose soil the worst of the war was fought, can be said never to have fully recovered from the conflict. They lost half a generation of young men, and memories of that conflict, along with its successor, World War II, are still rooted deeply in the French psyche. The Germans, Austrians, British, Russians and Italians also suffered grave damage and irreplaceable loss. Comparing relative suffering through comparative statistics is an empty exercise; every nation involved suffered immensely. There were no real victors.

The French, on whose soil the worst of the war was fought, can be said never to have fully recovered from the conflict. They lost half a generation of young men, and memories of that conflict, along with its successor, World War II, are still rooted deeply in the French psyche. The Germans, Austrians, British, Russians and Italians also suffered grave damage and irreplaceable loss. Comparing relative suffering through comparative statistics is an empty exercise; every nation involved suffered immensely. There were no real victors.

For America the war was relatively brief, and the casualties, while large, could not be compared with those of the other major nations. For America, however, the Great War was a turning point: for the first time American soldiers in significant numbers crossed the Atlantic to fight in a foreign war; for the first time America became deeply embroiled in European affairs; for the first time an American president helped shape the fate of a postwar world. For the first time America was part of the Western family of nations in the fullest sense, and the impact of the two million soldiers who fought in France remained for decades. President Wilson and the diplomats who negotiated the peace treaty in Versailles in 1919 changed the course of American diplomacy forever.

Few observers expected the war to last more than a year or so. The German General staff had devised a plan which might, in fact, have brought a swift conclusion to the war. Count Alfred von Schlieffen of the General Staff had devised a plan early in the 20th century. Addressing the possibility of fighting against both France and Russia at the same time, the Schlieffen Plan called for the German army to block the Russians in the East with a modest force while throwing most of its weight into a sweeping movement through northwestern France to capture Paris. To weaken French resistance against the main thrust, German defenses along the upper Rhine in southern Germany were to be light in order to draw the French army in at that point, thus enabling German forces to advance more rapidly towards Paris. Over the years, however, the plan was modified, and in the event, the German General staff overestimated the Russian force in the East and strengthened that front at the expense of the West. Some historians believe that had the Germans carried out their original plan, the war might have been over within the first few months. Instead, within months of the outbreak of fighting between Germany, France and Great Britain, the western front settled into a stalemate fought across trenches that stretched from the Swiss border to Belgium.

As mentioned above, the technology of the weapons of World War I far outstripped traditional military tactics and made old practices irrelevant and deadly. The armies were huge: the Germans mobilized 5 million men, and 4 million Frenchmen were available for the conflict. Russia had even more, but was slow to mobilize. The principle of mass was still seen as the key to victory, but the new weapons—machine guns, barbed wire, artillery, hand grenades, poison gas—made mass attacks a little more than suicide charges. In between the fruitless attacks, the soldiers had to endure the horrors of the trenches: the heat of summer and the wet and cold of winter. Millions of soldiers lived in little more than holes in the ground, where, in addition to the terror of enemy artillery, they had to endure mud, disease, rats, the stench of human waste, gas, constant fear, and shell shock. A British staff officer from London visiting the front broke down in tears and said, "My God, have we sent men to fight in this!”

Throughout 1914, 1915 and 1916 the fighting raged on both Eastern and Western fronts. In September 1914 the first Battle of the Marne was fought with 1,000,000 men participating on each side of the line. Within a matter of days the Allies lost 250,000 men, and the Germans lost even more. This was the most decisive battle since Waterloo. Afterwards the trenches extended from Switzerland to the North Sea/English Channel, and for the next four years neither side was able to break the other.

The Naval War in 1914. Sea power, unappreciated by the French, soon began to make itself felt. The British and German navies fought it out on just about every ocean of the world; colonies would become bargaining chips later. By the end of 1914 Great Britain was in command of the seas, and a naval blockade soon began to pinch the Central Powers; the German submarine, “U-Boat,” was the only effective weapon left to the Germans.

The Russians advanced rapidly westward to assist their French allies in 1914 but were decisively defeated by the Austrians at Lemberg and the Germans at Tannenberg. The Germans defeated the Russian army decisively, taking 90,000 prisoners; the results could have been worse for the Russians, who were poorly led and equipped. German General Ludendorff took command, with Field Marshall Hindenburg as the nominal head, and cut off the Russian “steamroller.” The Russians had terrible counterintelligence; they sent teletype messages in the clear, allowing them to be easily intercepted, and were otherwise careless of military security. Nevertheless, the German General Staff had greatly overestimated the military power of the Russians, whose vast numbers proved ineffective in modern war.

By end of 1914 it was apparent that huge economic resources had been expended, and much more would be required. It had become a war of money and supplies, which affected, among other things, the position of America. The United States was a huge, wealthy industrial giant that had the means to supply the warring parties with much of what they needed to prosecute the war. The Morgan bank, which had historic ties (and offices) in England, loaned large sums of money to the Allied side. According to British historian Liddell Hart, prewar economists were “dumbfounded” by the economic demands of the conflict.

1915. The German strategy for 1915 was to hold the French and the British in the West and achieve a decisive victory in East, knocking Russia out of the war. Renewed offensives in the West, however, included the battles of Ypres and Artois. Poison gas was used for the first time by both sides, but it was hard to use effectively because of wind shifts, etc. Still, it was a horrifying weapon, and thousands of soldiers coughed out their lives. The French mounted major offensives in the summer and fall. There were huge costs, but no results, except recriminations among the British and French generals who blamed each other for the failures.

The invasion of Gallipoli in the Dardanelles, the Strait between Greece and Turkey, was Winston Churchill's brainchild. His idea was to assist Russia, open a second front, and use the “indirect approach” to get at the “soft underbelly” of Europe. There was much resistance to the plan, but it was overcome. A huge expeditionary force landed in the Dardanelles, but it got stranded and eventually had to withdraw. Critics thought Churchill’s reputation had suffered irreparable damage.

The invasion of Gallipoli in the Dardanelles, the Strait between Greece and Turkey, was Winston Churchill's brainchild. His idea was to assist Russia, open a second front, and use the “indirect approach” to get at the “soft underbelly” of Europe. There was much resistance to the plan, but it was overcome. A huge expeditionary force landed in the Dardanelles, but it got stranded and eventually had to withdraw. Critics thought Churchill’s reputation had suffered irreparable damage.

In 1915 Italy turned sides and declared war on Austria. Italy wanted territory, and to regain her “historic traditions.” The Italian commander lost over 250,000 men by December to the Austrians waiting in the mountains with their machine guns. By August 1917 the Italians had fought 11 “Battles of the Isonzo River”—and were still on the Isonzo.

In the East the Russians tried to defend against a German offensive. The Germans, however, won a major battle at Masurian Lakes, taking another 90,000 Russian prisoners. Although the Russians were able to advance against the Austrians, by September, 1915, the Germans broke through, and the whole Russian front was soon in a state of collapse. Russia lost 2 million men, half of them captured. Facing critical shortages of supply, the Russian army was no longer a serious threat. At the same time, the coming Communist revolution was undermining Russian unity and demoralizing the Russian army.

Fighting also occurred in Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia. The British needed to protect their source of oil supplies in the Persian Gulf region. In 1916 Colonel Thomas E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”) emerged as a spectacular war hero; he led Arab forces in their revolt against the Ottoman Turks. Using guerrilla tactics, Lawrence and his Arab soldiers destroyed railroads and other installations. In a daring aid across an “impassable” desert, he captured the city of Aqaba. Serbia was also conquered by Germany and Austria in 1915-16. (See the film Lawrence of Arabia with Peter O'Toole. Lawrence published an autobiographical account of his exploits in the war, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, in 1920.)

Net result of 1915 fighting: 600,000 German casualties, 1,300,000 French, 279,000 British with “no appreciable shift in the lines.”

1916. It was now thought that the Western front was crucial and that the allied effort should be focused there. The Germans reversed their 1915 strategy and tried to crack the Western front, thinking that the French had suffered huge losses and might crack under a strong blow. The year marked the first appearance of tanks, created as mobile pillboxes to serve as a countermeasure against machine guns and barbed wire, which had chewed up men by the thousands. Major battles included Verdun and the Somme. At the Somme a seven-day artillery bombardment was followed by an attack on a 14-mile front. The deadly machine gun led to 60,000 British casualties (19,000 killed) in one day. Total losses in the campaign reached about 600,000 on each side. A French counterattack to retake ground lost in Verdun offensive cost about 500,000 losses on each side.

The Battle of Jutland in 1916 was the high point of the war at sea. The British fleet numbered 151 vessels, the German fleet 99. The fighting went on for two days and a night, and the British lost 14 ships, the Germans 11, but the results were negligible in terms of overall war gains. The decisive battles were fought on land.

Germany issued the Sussex pledge, promising to end unrestricted submarine warfare.

In 1917 the United States entered the war as the situation of the Allies was growing increasingly worse. American troops, however, did not begin to arrive in Europe until late 1917 and early 1918. The Battles of Passchendaele and Cambrai saved the French army from total defeat but otherwise produced no positive results. Also in 1917 the Germans provided safe passage for Bolshevik leader Lenin from Switzerland to Russia in the hope that a communist revolution would permanently remove Russia for the war. The Germans got their wish, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed on March 3, 1918, ending fighting on the Eastern front.

America Goes to War

Germany breaks the Sussex Pledge. The costs of the war, as has been stated elsewhere, were horrendous. Soldiers died by the tens of thousands; millions of bullets and artillery shells were fired; poison gas, barbed wire, the machine gun and heavy artillery made the life of the infantryman a hellish nightmare. Miles of trenches with very poor sanitation and few comfort facilities bred disease and despair. By 1917 both sides had bled and suffered almost unbearably—it seemed as though the carnage would never and end. Germany finally decided to try to achieve victory with one big push. Russia, apparently neutralized by both the ineffectiveness of the Tsarist army and by the impending Bolshevik Revolution, was no longer a serious factor in the East. So the German high command decided to focus attention upon the West and planned a  huge offensive for 1917 and 1918 to try to end the war once and for all. As part of that plan, they made a decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, breaking their Sussex pledge of 1916.

huge offensive for 1917 and 1918 to try to end the war once and for all. As part of that plan, they made a decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, breaking their Sussex pledge of 1916.

When news of the German decision reached Washington, President Wilson was pushed to his limit, as he had warned Germany in 1916. The situation was exacerbated by the infamous Zimmermann telegram, in which the foreign ministry in Berlin instructed its minister in Mexico to approach the Mexican government and urge them to join Germany in a fight against the United States. In exchange, Germany would help Mexico redeem the territory it had lost to the United States as a result of the Mexican War: most of the southwestern United States, including California. British intelligence had broken the German codes and thus had the Zimmermann message, which they withheld from the United States, not wanting to reveal their coup. But they finally decided that having the United States in the war was more important than guarding intelligence secrets, and the message was forward to Washington.

Reluctantly, President Wilson went before Congress and asked for a declaration of war. He told Congress, “It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance.” His speech was greeted with applause, causing him to remark to an aide as he was leaving the chamber that he found it strange for men to applaud a decision which would send thousands of other men to their deaths.

To get a good feel for President Wilson’s handling of the war issue, one should read carefully the excerpts from his speeches, including his Neutrality Address, the Fourteen Points, and his Peace without Victory speech and his War Message. See also Senator Norris's speech in opposition to the war.

Over There

As soon as Congress declared war, America started mobilizing resources in preparation for joining the conflict in Europe. The task was daunting, as America had continued to embrace neutrality and was woefully short of military supplies and weapons. Recruiting efforts supported by a draft, however, saw the U.S. Army grow from 200,000 to 4 million men. By the summer of 1918 some two million Americans had reached Europe with no casualties, a credit to the U.S. Navy, which mobilized 800,000 officers and sailors to man the fleet. The U.S. dispatched 42 Army Divisions of 26,000 to France—a total of 1 million combat soldiers. When the American divisions began to arrive, the French high command was desperate because of near mutinies, casualties and desertions among its soldiers. French generals wanted to feed the American soldiers into the lines piecemeal, but General John J. Pershing, the American commander, insisted that American units fight together under American officers.

In addition to building up an effective ground force, the American command began creating aviation units, which by 1918 were beginning to have a significant impact on the ground action. American pilots were trained and led in many cases by veterans of the Lafayette Escadrille and the Lafayette Flying Corps. They were American volunteers who had flown with the French since 1916. (Their motto was, “God forget us if we forget/The sacred sword of Lafayette,” reference to the French hero of the American revolution.)

In the spring of 1918 American units entered the fight in small numbers, and by summer American soldiers and Marines of the U.S. Second Army Division joined the battle at Chateau-Thierry and participated in the 2nd Marne counteroffensive. Later that summer nine American divisions took part in the Meuse-Argonne campaign, and the Allies began to advance across the entire western front. Among the American officers serving in France were colonels Douglas MacArthur, George Marshall, and George Patton, as well as Captain Harry S. Truman, whose artillery battery fired thousands of shells during the summer’s fighting. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt visited the American front lines and was deeply affected by the sight of troops coming out of the battle zone. Those images were burned into his memory, as he recalled in a speech some two decades later. In a speech in Chautauqua, New York, in 1936, FDR said, “I have seen war. … I have seen 200 limping, exhausted men come out of line—the survivors of a regiment of 1,000 that went forward 48 hours before. … I hate war”.

In the spring of 1918 American units entered the fight in small numbers, and by summer American soldiers and Marines of the U.S. Second Army Division joined the battle at Chateau-Thierry and participated in the 2nd Marne counteroffensive. Later that summer nine American divisions took part in the Meuse-Argonne campaign, and the Allies began to advance across the entire western front. Among the American officers serving in France were colonels Douglas MacArthur, George Marshall, and George Patton, as well as Captain Harry S. Truman, whose artillery battery fired thousands of shells during the summer’s fighting. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt visited the American front lines and was deeply affected by the sight of troops coming out of the battle zone. Those images were burned into his memory, as he recalled in a speech some two decades later. In a speech in Chautauqua, New York, in 1936, FDR said, “I have seen war. … I have seen 200 limping, exhausted men come out of line—the survivors of a regiment of 1,000 that went forward 48 hours before. … I hate war”.

Although new to the action, American combat troops fought fiercely during the four months of action they saw. According Marine Corps lore, the Germans called American Marines “Teufelhunde”—“Devildogs.” Likewise, American soldiers were seen by the Germans as men who would smile one minute and bayonet an enemy the next. Without doubt the fresh American forces turned the tide. Although previously untested, the Americans quickly grasped the tempo of modern warfare and became a significant factor in holding back and eventually repelling the German onslaught. It must be noted, however, that the Germans had been fighting for four long, bitter years; they were mentally and physically exhausted, though they continued to fight valiantly.

By late September and early October, 1918, the Germans, although still on French soil, were in full retreat, and in late October the German high command sued for peace based upon Woodrow Wilson's 14 Points. Thus, although Americans had participated in the war for only the few final months of the long and terribly bloody four-year conflict, they made a significant contribution to the outcome of the war. It is entirely feasible that the Germans would have won had the Americans stayed out.

German General Ludendorff had tried to end the war with a massive campaign before Americans got into the fight. The Germans launched their Great March Offensive in 1918, breaking through in several locations. Paris was bombarded by artillery from a distance of 65 miles, and over 800 were killed in that city. German bombers actually reached England, causing minor damage even while shocking the population. But with the arrival of fresh American troops, the German plan to end the war in their favor collapsed. Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated and fled to Holland, where he died in 1941. At the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month—November, 1918—the guns fell silent and the lights went on again all over Europe. But there was little joy, only relief. For years thereafter, November 11, today’s Veterans Day, was celebrated as Armistice Day.

World War I on the Home Front

When he set out to create an army “to make the world safe for democracy,” Wilson kept his progressive ideals in mind. He worried about American people’s willingness to accept the war, and he did everything possible to sell the war to the American public. He instituted a draft rather than relying on volunteers, simply because it was more efficient. He created a Committee on Public Information that provided for posters bearing patriotic mottoes, speeches in theaters, and so on. Wilson also called for legislation to prevent dissent and sabotage—the Espionage Act, the Trading with the Enemy Act, and the Sedition Act. Section 3 of the Sedition Act reads, in part: “

Whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully make or convey false reports or false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces of the United States, or incite insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States, or ...shall willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States ... shall be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both.”

Civil libertarians have found such measures excessive, but they are typical in wartime. The American people probably supported the war far more willingly than Wilson imagined, perhaps because he had doubted the wisdom of taking America in for so long himself. In any case American civilians got into the war mood with a vengeance, making life difficult for German-Americans and any American whose patriotism did not measure up.

Despite progress made in American military organization since the time of the Spanish-American war, America was in many ways ill-prepared to enter the First World War. Army-Navy cooperation was not all that it should have been. Despite the submarine threat, however, the Navy transported 2 million American soldiers to Europe without losing a single man or ship to enemy action.

While the army had no difficulty building up numbers, the demands of training and supply were overwhelming. By the time the Yanks got into battle, they were fighting with mostly foreign-made equipment. (I have in my possession letters from my father, written while he was in training at Plattsburgh, New York, prior to heading to France in 1917. In those letters he reports using makeshift equipment, including wheelbarrows as make-pretend vehicles and brooms for rifles. He wrote to his parents that the only decent weapon they had was the French 75 mm howitzer.)

The United States was a nation of huge industrial power. For example, there were as many miles of railroads in United States as in most of the rest of the world combined. The mobilization effort that followed America's entry into the war was stupendous. The War Industries Board was created under the direction of Bernard Baruch, and although the United States government left the ownership and direct management of industrial affairs in private hands, it oversaw the efforts of American industry and oriented them toward the war effort. In coordinating the mobilization effort the government also took control of communication and transportation, including railroads, telephone and telegraph. While not totally abandoning the traditional American practice of laissez-faire, the government nevertheless took far more active control of American business than it ever had done in peacetime.

A serious matter facing the allies was the supply of food. At the time the United States entered the war, Great Britain was perilously close to running out of food for its civilian population while desperately trying to keep its troops supplied. The administration of American food production was turned over to Herbert Hoover. His task was monumental. As an accomplished engineer and superb manager, Hoover managed to increase American food production enormously, increasing the amount of bread, meats and other commodities by large amounts. The American people were encouraged to voluntarily support Hoover's food program by observing wheatless Mondays, meatless Tuesdays, pork-free Thursdays, and so on. People were also asked to plant victory gardens and reduce their use of electric power. The need for more food also furthered the cause of prohibition as crops were diverted from the production of alcohol to the production of bread. Hoover's program to prevent starvation in Belgium was later recognized for its humanitarian contribution.

A serious matter facing the allies was the supply of food. At the time the United States entered the war, Great Britain was perilously close to running out of food for its civilian population while desperately trying to keep its troops supplied. The administration of American food production was turned over to Herbert Hoover. His task was monumental. As an accomplished engineer and superb manager, Hoover managed to increase American food production enormously, increasing the amount of bread, meats and other commodities by large amounts. The American people were encouraged to voluntarily support Hoover's food program by observing wheatless Mondays, meatless Tuesdays, pork-free Thursdays, and so on. People were also asked to plant victory gardens and reduce their use of electric power. The need for more food also furthered the cause of prohibition as crops were diverted from the production of alcohol to the production of bread. Hoover's program to prevent starvation in Belgium was later recognized for its humanitarian contribution.

The government also went out of its way to try to control public opinion. A committee on public information was created under the leadership of Chairman George Creel. Artists were mobilized to design posters. Thousands of amateur and professional were organized as “four-minute men” to encourage the public to buy war bonds, support the draft and help with food production programs. They spoke in churches, movie houses, and other public gatherings in an attempt to mobilize support for the war. German-Americans bore the brunt of much of the public opinion mobilization effort, as anything German became out of bounds. German-American clubs had to change their names, and schools stopped teaching the German language. Even violinist Fritz Kreisler was booed when he appeared on the concert stage.

People who spoke German stopped using it in the streets for fear of reprisals. One German-American citizen was stripped naked, wrapped in an American flag, and lynched in St. Louis, Missouri. Finally, a Sedition Act was passed in 1918 that made it illegal to write or print anything disrespectful of the government of the United States. Many who protested the war were jailed, a direct slap against America's traditional position of freedom of speech. For example, labor leader Eugène Debs was jailed for a speech in which he questioned whether America's war effort was in the best interests of American workers. The freedoms for which President Woodrow Wilson professed to be fighting were in fact jeopardized on the home front; since this was America's first involvement in a major European war, however, the American people acquiesced in many of these measures.

The Paris Peace Conference, 1919, and the Treaty of Versailles

When the Germans surrendered, President Wilson made a fateful decision: He himself would go to Versailles to help write the terms of peace. (He had earlier declared it unthinkable that America should have no role in that great enterprise.) He wanted a “peace without victory,” a generous peace, but the allied leaders who had suffered so fearfully would have none of it. Wilson’s goals, outlined in his Fourteen Points, called for a lasting peace based on national self-determination among the nations and an international peacekeeping organization, and that was partially realized. Wilson was unable, however, to prevent the victors from saddling Germany with enormous reparations and restrictions, which in retrospect can be called at best unfair.

Not only was the First World War one of the most terrible wars ever fought, the decades-long buildup to the war was based on agreements, generally secret, of great complexity. Furthermore, if you examine the declarations of war contained in the appendix, you can easily see that many interests were represented by the warring powers, and their representatives came to Paris to participate in the division of the spoils. Issues of territorial rights, sovereignty, disposition of populations, location of international boundaries, trade, and ownership of capital assets were just some of the matters to be addressed by the hundreds of delegates who converged on Versailles in January, 1919.

President Woodrow Wilson was the first incumbent United States president to set foot on European soil. Given the decisive role that the United States had played in the last months of the war, Wilson was welcomed in Europe as a conquering hero. During a triumphant tour in England, France and Italy, he was cheered by thousands and welcomed into the inner circles of their governments. Considering the losses suffered by the other major powers during the brutal conflict, however, it was not surprising that the European leaders soon began to feel resentment toward the Americans and their leader.

In theory, since Germany was excluded from participation in the negotiations (a decision which was contrary to customary practice until that time), the great conference might well have been devoted to the settlement of a fair and equitable peace by the victors. In fact, rivalries and jealousies ran rampant throughout the negotiations. Having lost so much of their blood and treasure to the enemy, the other three of the big four leaders besides Wilson—Lloyd George of Great Britain, Orlando of Italy, and Clemenceau of France—were in no mood to be generous. The lesser players at the conference also had their own agendas based on their participation in the war. President Wilson tried unsuccessfully to focus the negotiations on his Fourteen Points, most of which were seen as too idealistic for practical leaders who wanted something in return for their sacrifices. (Clemenceau grumped at one point, “God has 10 Commandments; but Wilson needs 14 points!”)

The League of Nations. Woodrow Wilson was nothing if not idealistic. One of his dreams was for an international organization that might serve to maintain order among the world nations and to keep the peace. The question in 1919, a question that remains even to this day, is the degree to which nations might be willing to sacrifice a significant portion of their sovereignty to a higher body. The chief issue, which was also an issue that faced the United States Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, was the issue of large states versus small states. In an international context, would the major nations of Germany, Japan, Great Britain, France, the United States, and Russia, be willing to concede the right to make decisions of international import to a body which might be dominated by smaller nations with little to lose?

In addition to the demanding negotiations taking place in the great Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, Wilson personally spent much of his remaining time drafting the charter of the League of Nations, with the assistance of his American advisers. His ideas emanated from the last of his Fourteen Points: “A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.” Unfortunately, after failing to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, the United States also refused to join the League. President Wilson won the Nobel Peace in 1919 prize for his efforts, but the League lacked the power to prevent the rise of dictators or to prevent the outbreak of yet another world war.

“A Peace to End All Peace.” Intent as he was on bringing the League of Nations into existence, Wilson saw his idealistic goals disappear one by one. Wilson remained in Paris until June, returning home once to sign legislation and attend to other presidential business. In his absence, the delegates at Versailles watered down more of Wilson’s initiatives. After taking months to draft the treaty, the conferees presented the document to the German delegation, who had not been permitted to participate in its creation. Given forty eight hours to accept the treaty under the threat of renewed hostilities, the Germans humbly accepted. The bitterest pill for the Germans was Article 231, which placed all blame for the Great War on Germany’s shoulders. Along with crippling reparations and economic sanctions, the “war guilt clause” added insult to real injury. Future German dictator Adolf Hitler would later use the harsh provisions of the Versailles “Diktat” to whip the German people into a frenzy of support for his aggressive policies.

The term “a peace to end all peace” comes from the title of David Fromkin’s book, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, (New York, 2001.) Fromkin analyses the results of the Versailles conference.

Wilson had taken no Senators, nor any Republican leaders, with him to Paris, a serious flaw in his desire to achieve his goals. The United States Senate, which would have to ratify any treaty signed by President Wilson, was controlled by the Republican Party. Thus while Wilson was in Europe for the best part of six months, having been greeted by the European people as a conquering hero, Republican leaders in the Senate fretted, stewed and awaited his return with bated breath.

Wilson had taken no Senators, nor any Republican leaders, with him to Paris, a serious flaw in his desire to achieve his goals. The United States Senate, which would have to ratify any treaty signed by President Wilson, was controlled by the Republican Party. Thus while Wilson was in Europe for the best part of six months, having been greeted by the European people as a conquering hero, Republican leaders in the Senate fretted, stewed and awaited his return with bated breath.

When Wilson presented the Treaty of Versailles to the Senate, they balked. Wilson was tired and in poor health from his exertions in Europe, and was in no mood to compromise. Neither was Senate leader Henry Cabot Lodge. It soon became apparent that Wilson would not accept the treaty with the reservations which the Senate proposed, and the Senate would not ratify the treaty as presented to them. Thus a standoff existed, and Wilson decided, unwisely as it turned out, to take his show on the road.

The president set off on a train trip around United States designed to take his case directly to the American people. He hoped he could persuade them pressure Senators to accept his treaty without reservations. While on the trip, however, Wilson became ill and was rushed back to Washington, where he suffered a serious stroke. For weeks President Wilson was unable to conduct business. As mentioned above, Wilson’s wife, Edith Galt Wilson, did her best to conduct affairs on her husband’s behalf. In addition to controlling access to her husband, she delivered all communications to and from the ailing President. Vice President Thomas Marshall was given no access to the ailing president, a factor considered years later in the passage of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment.

In the end, the United States never ratified the Treaty of Versailles and concluded a separate peace with Germany in 1921. The fact that the Versailles Treaty turned out to be disastrous in many respects was not Wilson's fault. He does, however, bear some responsibility for America's withdrawal from the international debate, leaving the European nations to struggle to maintain peace even as they drifted inexorably towards the next world war. Woodrow Wilson died in 1924 and is buried in the Washington National Cathedral.

The Aftermath of the War and Wilson's Legacy

THE HUMAN COSTS OF WORLD WAR I Given the number of casualties, these generally accepted figures must be considered estimates. |

||

LOSSES |

KILLED |

WOUNDED |

Great Britain |

947,000 |

2,122,000 |

France |

1,385,000 |

3,044,000 |

Germany |

1,808,000 |

4,247,000 |

Russia |

1,811,000 |

4,950,000 |

Italy |

651,000 |

947,000 |

Austria-Hungary |

1,200,000 |

3,620,000 |

Turkey |

325,000 |

400,000 |

United States |

116,000 |

206,000 |

| During World War I soldiers died at the average rate of about 6,000 per day for 4 years, 3 months. There were also nearly 10 million prisoners. | ||

TOTAL COSTS of WORLD WAR I:

The war made massive economic planning necessary—massive industrial mobilization was necessary to support the war effort. Rapid inflation and severe economic impact were results—huge national debts caused higher taxes for years. Severe morale problems arose among civilians. For much of the war rigid censorship was imposed; people at home first began to realize the impact of the war when train-loads of coffins and cars filled with thousands of wounded soldiers began to arrive at the terminals in Berlin, Paris and London. As horrible as it was, the conflict would be resumed two decades later. |

||

| World Power Home | Imperial America | World War I Home | Updated January 28, 2018 |