Introduction

Here I abandon my role as a historian and adopt the role of commentator. As a preface I would state that I do not consider myself aligned to either political party: I have voted for candidates of the two major parties, and for candidates of others, such as the Libertarian Party. I have always tried to vote for the man or woman I considered most capable of fulfilling the duties of the office for which he or she was running.

Over the course of my study and teaching of history I have read biographies of 25 presidents, multiple biographies of the important ones. In the course of that reading I have come to believe that there are certain qualities of good presidents that most of them share: honesty, humility, respect for the Constitution and the institutions that make our democracy, including the press, humility, willingness to work on comfortable terms with members of the loyal opposition, and the placing of the national interest above one's own political aspirations. Even our poorer presidents had many of those qualities. I suggest that students of the highest office use the foregoing criteria to evaluate our commanders-in-chief along with their accomplishments to judge the persons who held that office.

What follows in this section is what one might call incomplete history. I have always held to the traditional belief that events that happen do not become “history” until historians and other observers have had time to uncover all the hidden facts and reflect upon the causes and results. Sometimes things that happen appear to be settled; causes are easy to discern, and a logical chain of events can be constructed. But that process is not always as easy as it seems. History is not an exact science—in its best form, it is a careful analysis of past events performed in the hope of determining exactly what happened and why.

Some years ago, as I approached my campus on the first day of the semester, the entrance I normally used was blocked because of an accident. I made my way to my classroom building by another route and then walked out to observe the scene. It was obvious from the position of the cars and the skid marks that a vehicle had apparently gone through a red light and been struck broadside by another car moving at a fairly high rate of speed. As I was observing the scene, a helicopter landed on a field behind me, and shortly thereafter an ambulance came up the hill from the accident and loaded a body on a stretcher into the medevac aircraft.

Later I took my class out to observe the accident scene, and as a lesson in reconstructing historical events, I asked them how much we could know about what happened, even if we had been eyewitnesses to the accident itself. What were the two drivers thinking moments before the crash? Had one or both of them been distracted perhaps by a pedestrian at the intersection? Had one of them been lighting a cigarette or fiddling with the radio dial? It might be possible to interview the drivers, but as we learned from the news later that day, the driver who had been medevaced in the helicopter had died. After discussion we concluded that we might be able to reconstruct 50% of everything that caused that accident. I then pointed out to my class that we were going to examine events that occurred 200 years ago and study it as if we could learn why everything happened. The historical challenge is obvious.

The point is that it takes time, effort, and many hours of research to uncover causes and effects of historical events, and even after that, it is unlikely that we will know everything we need to know in order to determine exactly how and why those things happened. Even events as old as the American Revolution and the Civil War are still being reevaluated as new bits and pieces of evidence are discovered.

The New Millennium

When the clock turned from December 31, 1999, to January 1, 2000, the world breathed a sigh of relief. All the fears associated with the term Y2K—what was supposed to happen to computers and computer systems when their internal clocks flipped from 99 to 00—turned out to be negligible. Airplanes did not crash, financial assets were not frozen, communications functioned properly, power plants did not shut down, and even personal computers made the transition without a hiccup. It seemed as though the new millennium had dawned with hope, even though the year 2000 was the last year of the old millennium rather than the first year of the new one. That didn't matter; writing 2000 on our checks was a visual reminder that times had indeed changed.

The new millennium began full of promise. The American economy was doing well. The Cold War was over, and it was anticipated that resources could be moved from extraordinary defense expenditures into more productive areas. The age of modern communications meant that people were more connected than ever, and the ordinary desktop computer held more power to calculate than the monstrous, expensive computers that had existed 30 years earlier. Medical care was advancing, and scientific discoveries seemed to promise almost daily that there would be brighter days ahead in a variety of human endeavors. The dot com boom was in full swing.

When the actual first year the new millennium arrived, everything changed with shocking suddenness. On September 11, 2001, the attacks on the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and the aborted attempt on yet another government building, possibly the United States Capitol, changed America forever. Americans rallied around the flag and vowed vengeance to those who perpetrated that terrible evil. Before long airplane travel change drastically; no longer was a boarding pass all you needed to get to your seat on a commercial flight. New ethnic tensions arose as Americans contemplated the source of the attacks. For a while, the Cold War years seemed like the good old days.

Given America's propensity to take up arms in the face of perceived injustice, it was almost inevitable that the nation would launch a war against terror. The Gulf War of 1991 when United States drove the Iraqis out of Kuwait now appeared to be too little. American armed forces had stopped too soon and should have removed the threat perceived to have a home in Iraq, among other places. Although the Second Gulf War against Iraq removed Saddam Hussein from power, the attempt to transform that nation into a thriving modern democracy proceeded unevenly. Much of the justification for that war concerned so-called weapons of mass destruction. In the end, it turned out that the intelligence about those so-called WMDs was faulty. And without a clear exit strategy, America's involvement in Iraq dragged on for years.

The continuing search for the forces behind the 9/11 attacks then led the United States armed forces into Afghanistan. Although there might have been lessons learned from America's assistance to Afghanistan during the Russian occupation, those lessons did not necessarily translate into useful guidance in the search for Al Qaeda and America's enemies in the war on terror. American forces found and killed Osama bin Laden, but the world remained a dangerous place. Ethnic and religious tensions still operated along the borders between India and Pakistan, the Middle East, and even in Northern Ireland, where the violence was halted thanks to the Good Friday agreement of 1998.

More recently the attention Americans has been focused on our own internal economic affairs. The so-called dot com boom blew up, and over exuberance on the part of banking and other financial interests led us to one of the worst economic periods since the Great Depression. In fact, it led to what we now call the Great Recession of 2008-09. The stock market plunged, unemployment rose, and as the Boomer generation approached retirement age, Americans began to worry seriously about our ability to pay the bills that we had incurred over the years. Political divisions in the United States sharpened, and an age when politicians on both sides he could sit down and work out compromises to move the nation forward seemed to be a dream world that had disappeared. Government shutdowns were evidence of the great divide in the American political landscape.

Another image that tarnished the rosy picture that appeared after the turn of the millennium was that of school children and teachers huddled in fear as crazed persons with automatic weapons wreaked havoc in schools or churches, places that were once considered sacred, safe havens where people could learn about the world around them or worship a god of their choosing. Now the lessons that they learn have a different character; as they walk to their classrooms each morning, most children probably don't pay much attention to the guards and security people who of necessity find a permanent residence in our halls of learning. But they are there, and they will probably remain there, now that the desire to kill other human beings for some incomprehensible reason has become so common.

Recent Events. This section of the website will deal in more detail with the historical events that have occurred since the year 2000. But American history no longer seems to be a narrative; it has become for this historian a series of disjointed episodes that lack coherent context. Life does not progress smoothly in 21st century America; it jerks along from crisis to crisis, interspersed by periods of satisfying events such as the resurgence of the stock market beginning in 2013. But whereas in past decades, even in the dark hours of the Cold War, Americans to seemed to know what the future promised, that has become more difficult.

Future Shock by Alvin Toffler was written almost half a century ago, but the rate of change has accelerated manifold since then. Today's technology will be obsolete before the next year ends, or so it seems. We are deluged by information, the vast majority of it of minimal consequence at best. Yet we are told that unless we can get the latest message on our communication devices faster than the next person, we will somehow be losers in the great game of life. There is much to be celebrated: the presence of cancer in a person no longer automatically pronounces a death sentence. Airplane travel is far safer than it was even 10 years ago. Automobiles and trucks are more efficient and reliable than ever before. Modern communications devices allow us to have virtual movie theaters in our living rooms. All those things compensate; they do not, however, remove the causes of fear that overhang our lives.

How Things Looked in July 2014

How I got Here. Some of the events which I have recorded elsewhere in this site have led to tragedy, both national and human. In commenting on the state of affairs I shall review the course of events that have occurred during my lifetime. I was born in 1936 and began to gain awareness of the world outside my home when my father reentered the Army in which he had served during the First World War. I remember exactly where I was on December 7, 1941, at approximately 1:00 in the afternoon. I asked my grandmother what the news on the radio meant, and she answered, "It means we’re in the war."

I remember the day, April 12, 1945 when my third-grade teacher Miss Shaw walked into our classroom and with tears rolling down her cheeks and said, “The president is dead.” We all went home. I remember the day in August 1945, when the Japanese surrendered; cars roared around the streets, many of them convertibles with the top down and people seated up on the back of the seat blowing horns, shouting, and waving flags.

Thus, the primary events in the world around me during my early formative years were those of a nation of war. I lost a brother in that war, a half-brother whom I had never met. But I know my family was stricken by his loss, as he was my father's oldest child. I too served in the military and fought in Vietnam. I know many names on the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington DC. Some of them were friends and classmates, some were Marines in the unit I commanded. At this juncture all their deaths seem to a been a terrible waste. And since I fought in Vietnam, many more American men and women have gone to their deaths fighting in wars that also seem to me also to have been equally wasteful. One was fought over false premises, the other for over a decade, with no end in sight.

There is no way to know exactly why those events happened as they did, but we can speculate.

America Since World War II. In 1945 The United States was the most powerful nation in the world by any measure. America's homeland had been untouched by the war except for Hawaii, which was not yet a state. Its factories had poured out military equipment at a stupendous rate, supplying about 30% of all war materiel used by the Allies, including the Soviet Union. In early 1942 the production or delivery of cars was halted by the federal government. Ford, General Motors and the other auto companies started building tanks, airplanes and weapons.

Within months after the war had ended, factory output was shifted from wartime to peacetime purposes. Soon new cars, which had not been produced since early in the war, began to roll off the assembly lines. Houses were built to accommodate the returning veterans and their families. Consumer goods and modern appliances flooded stores, and Americans who had saved a lot of money during the war rushed to purchase those goods. The American economy absorbed the shock of millions of men being released from military service, and the postwar economic woes that blanketed much of the rest of the world from Europe to Asia were largely unfelt by Americans.

The United States was the only atomic power. America had more warships, planes and other military equipment than it could ever possibly use for the foreseeable future. The armed forces were pared down to a fraction of their wartime peak strength. Even as the Cold War developed, the thought of another global conflict in the age of atomic weapons had become too terrible for most people to contemplate. Tensions remained high for most of the 20th century, but the shot that launched World War III was never fired. Instead the world degenerated into a collection of squabbling ethnic groups, small nations trying to assert their power, religious fanatics bound to strip the world of unbelievers and major powers uncertain as to how to control the turmoil.

The postwar period from 1945 until the end of the century would fill out what became known as the “American century.” Although there were conflicts in which the United States did not become involved—the Chinese Civil War, the Hungarian revolution of 1956, the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, and others—America’s presence was felt everywhere. Although fighting had stopped in Korea, tensions remained. American troops were deployed to almost every continent, and American military aid was offered to the country’s allies. In the midst of all that, the American war in Vietnam divided the country bitterly.

On the political front, in the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union, when the Cold War was over and fears of a nuclear holocaust had subsided, national politics began to take an ugly turn. During the Cold War years politicians of both parties, realizing that the presence of a common enemy outweighed any domestic political differences, were able to join hands symbolically to get things done. That began to change when political disagreements took on a harsher note. Elections were contested with more bitterness than for much of American history. Although there was talk of “bipartisanship,” in reality, the two political camps became more divided, and even within parties, groups of extremists began to challenge their party’s political orthodoxy.

When Barack Obama was elected in 2008, many Americans celebrated it as a step forward in American race relations. Others were not so sure, and one factor in their discontent was the widespread belief that President Obama had not even been born in the United States and was perhaps a secret agent working for causes inimical to the country. The hope that American race relations might improve seemed futile. Government became more difficult, and discontent in the country deepened.

The State of Things in 2017

Because the United States was the most powerful nation in the world in 1945, its leaders naturally concluded that they were in position to shape world events, in other words, to control the behavior of other nations. This propensity to influence world affairs reinforced itself during the Cold War years. United States did influence the way other nations behaved, sometimes for good, other times, perhaps unintentionally, not for good. The posture that the nation adopted the guarding the rest of the world became essentially that of a control freak: Americans wanted to control everything, even things that in the final analysis were really none of their business.

Our current president seems concerned with controlling his image. This is not my conclusion; one hears that all the time from commentators. He is concerned with his legacy; his approval ratings have slipped and he is trying to project a more positive image. When will we ever learn that is it is the results of one's performance and the lasting achievements that result from it that ultimately determine what one's legacy shall become?

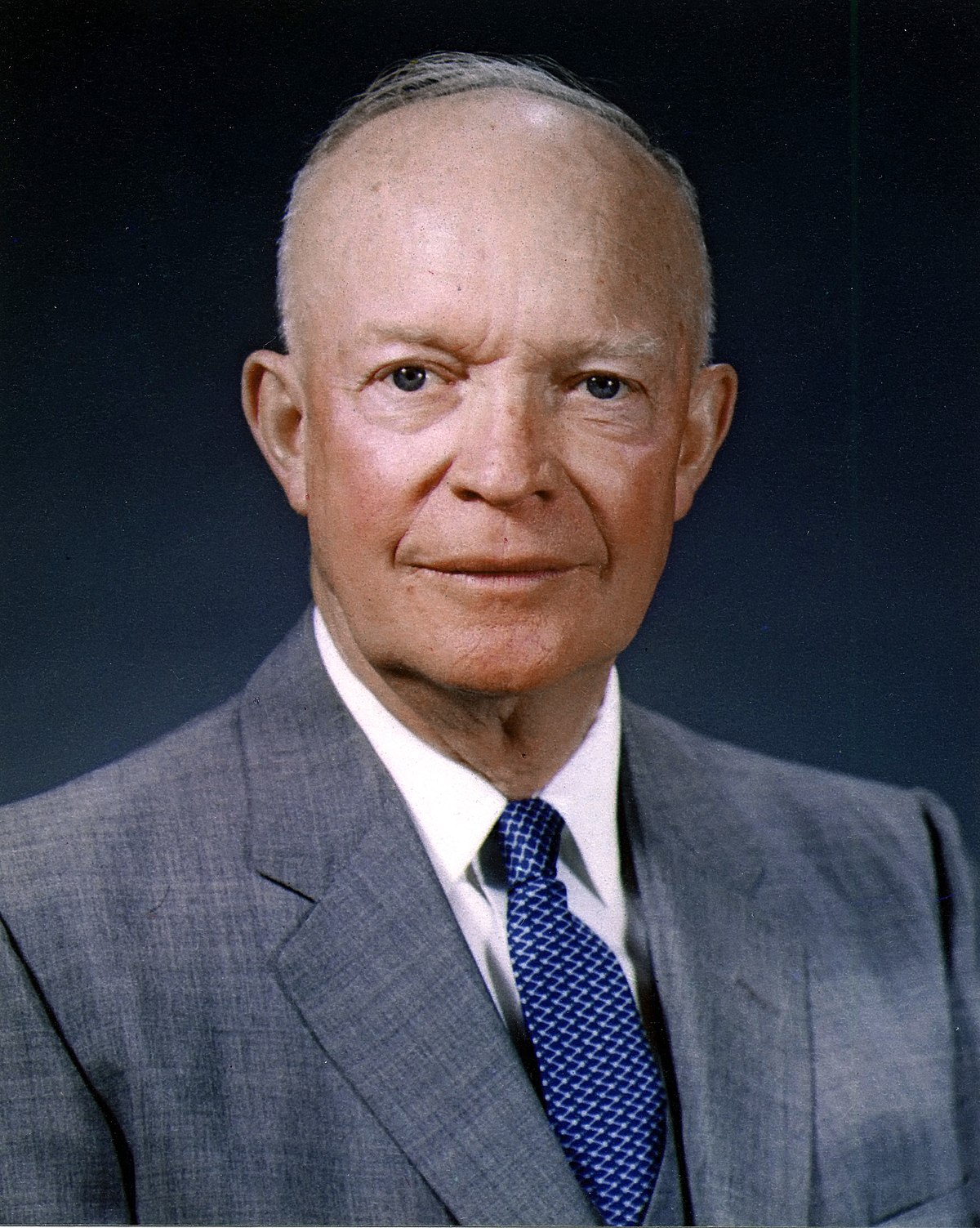

As historians look back on the presidents of the past, we can see that a presence legacy is shaped only over time. One such example is the legacy of President Dwight Eisenhower. I remember, for example, hearing jokes about “Ike.”

As historians look back on the presidents of the past, we can see that a presence legacy is shaped only over time. One such example is the legacy of President Dwight Eisenhower. I remember, for example, hearing jokes about “Ike.”

Question: "Did you hear that the president is dead?" Answer: "How could they tell?"

Yet today Eisenhower's presidency is looked upon as one of intelligence, common sense, and courageous restraint in the face of events elsewhere in the world, such as the Suez Crisis of 1956 and others mentioned above. He is not considered a great president, but a very good one. Most of that assessment has emerged as his record is compared with those of his successors. How many people, more than fifty years after he left office, remember the little things he did that might have affected his image in the short term? In the first place, it would never have occurred to President Eisenhower, who had overseen the European portion of the most terrible war in history, to think about little things that might affect his image. His farewell message to the nation might have been seen as such an effort, but I see it as a cautionary lecture. Be smart, use common sense, make sure that what government and her other institutions do is in the best interests of the nation in the long run.

Where are we now? Here in May 2017, we find ourselves as a nation in unprecedented territory. Confusion reigns in Washington, and in most of the country. New story lines appear almost hourly, so it seems. A well-known and highly respected commentator said this week that when she arrives home in the late afternoon from her workday, she takes a deep breath and hopes that, “My evening won’t be blown up again.” She had been called into a major news network to appear on its late evening shows for 23 days in a row.

The numbers are stunning. For the first time in the modern age, an incumbent president’s approval ratings are below 40% four months into his administration. The possibility of impeachment is being discussed everywhere, including on the floor of the House of Representatives, the body that would have to bring the articles if such a path were to be followed.

A boom in the stock market following an election is usually based upon expectations of what the president-elect hopes to accomplish after taking office. In 2017 it became clear that the wheels of government were not going to turn faster merely because the president decreed that they should. The markets faltered, volatility rose as people didn’t know what to expect next, and then following the worst day in the market since September 2016, it seemed to rally again. Who knows what will happen tomorrow?

Here in May, 2017, we find ourselves as a nation in unprecedented territory. Confusion reigns in Washington, and in most of the country. New story lines appear almost hourly, so it seems. A well-known and highly respected commentator said this week that when she arrives home in the late afternoon from her workday, she takes a deep breath and hopes that, “My evening won’t be blown up again.” She had been called into a major news network to appear on its late evening shows for 23 days in a row.

The president has just embarked on a journey which will take him to five different foreign locations, Saudi Arabia, Jerusalem, the Vatican, Brussels (the home of NATO) and finally to a G-7 summit in Sicily. As inside stories of life in the administration leak out, it has been claimed that the briefings for the president prior to these visits have been limited to one or two pages per country, on the assumption that any more than that would be difficult for him to absorb. People close to him say that he never reads. His actions in recent days have raised doubts about his ability to continue productive relationships with some of America’s closest allies.

Yet the president continues to have his supporters. A hard-core of maybe 30 to 40% of the population continues to believe that he will be able to “drain the swamp,” and “make America great again.” Whether he will be able to do that remains to be seen. It has been claimed that when the president seems to be making modest progress toward his stated goals, he “shoots himself in the foot,” a phrase that is heard regularly on the various news outlets. Discussions of the president’s apparently erratic behavior are not limited to the American media. European news outlets, magazines and newspapers are heavily invested in the drama being played out in Washington.

Where all this will take the nation remains to be seen. Many Americans, obviously more than his hard-core of supporters, would like him to succeed. The broad-brush strokes of his policy agenda gain high approval: tax reform, rebuilding of our infrastructure, updating the health care system, improving our financial organizations, and so on, are shared by a majority of Americans. What is lacking is confidence that he will be able to pull that off at all, let alone within the first year, as he had initially hoped.

How Things look in April 2020

As I write this in April, 2020, we are in the midst of the corona virus pandemic, and no one knows how this is going to wind up. Important political events have already been affected, and we have no idea what the result will be. One thing I can say for certain at this juncture is that when 2021 arrives, the United States will be a very different place. Damage is being done on multiple fronts, and it will not easily be corrected.

Do I have opinions about everything that has been going on over the past few years? Of course, I do, and so do many other people, and they are more strongly felt than at any time I can remember in my lifetime, and my memories of American politics go back to the last years of President Franklin Roosevelt. (I remember exactly where I was when I heard of his death in 1945.) I have decided to keep most of those opinions to myself in the hope that the information on this website will be useful to people of all political persuasions. When I retired from teaching, an older woman who had taken all of my courses, most of them twice, said that she didn't know whether I was a Republican or Democrat, and as a career government civil servant she was very attuned to politics. I have always been very proud of the fact that I was able to keep my political opinions out of my classroom. I will continue that practice here.

Resources: How to Evaluate the Rapidly Changing World in Which We Live

Aside from concerns about the political landscape and the impact of the corona virus pandemic, one thing that concerns me deeply is the growing impact of the uses and abuses of technology as it affects our daily lives. I am not oblivious to the benefits of the technology revolution: I taught online for 10 years, and found it a rewarding experience, both in terms of what it did for me, and what it did for my students. But the overwhelming assault on our privacy and the reckless use of our private information for monetary purposes disturbs me. Every device in our home, from cell phones to computers to smart TVs to smart appliances to gadgets like Alexa and other electronic communication devices monitors records and sends out everything that we say or do to be used for monetary purposes. It's beyond just robo calls and annoying ads: it's about the use of our private lives as a resource to be capitalized on by others. Many of the works below focus on this issue.

Books and Magazine Articles

|

Films

|

Web Sites

|