The American Revolution Begins: 1761-1774

In the Introductory Section we discussed the background events of the resistance movement that was about to begin. We pick up here with the first decade and a half of the revolutionary era, the period when, according to John Adams, the real revolution occurred. As he later described it, the war was not the revolution, but merely the result of it. Here we look at why that is true.

|

In 1763 the British Empire stretched around the world, from North America to India and points in between. The casual, haphazard system of colonial governance would no longer be sufficient. The mighty empire required administration and leadership far beyond that to which the colonies had become accustomed. Furthermore, the long series of wars had left the British deeply in debt, and Britain’s far-flung possessions would be costly to manage. All the same, Great Britain was a wealthy nation, though a great portion of the wealth lay in private hands. Where would they find the resources necessary to retire that debt? British officers who had served in America during the French and Indian War returned home to report a prosperous colonial enterprise, whose cities of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, although perhaps not up to the standards of London or Paris, nevertheless contained a population of approximately 1.5 million people, most of whom were prospering. America was now too large to be ignored and wealthy enough to be exploited. In order to do that, they had to tighten the rules. |

The Revolution Begins. The influence of the Enlightenment had touched America, and radically new ideas of government including that of republicanism had reached across the Atlantic. Because of such things as the Puritan emphasis on reading and the general prosperity of the average citizen, Americans were quite familiar with the new ideas being propounded by the likes of Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and other philosophes of the French salons and were well versed in political philosophy from reading John Locke. American ideology also emphasized the idea of “virtue” as a necessary component of political structure—an idea from the Enlightenment.

Of all the shortcomings of British management of their American cousins, their failure to perceive the political sophistication of the colonists was a crucial flaw. A second major misunderstanding lay in the British perception that although they had neglected to enforce various import and export restrictions for decades, the colonists would understand their responsibilities as parts of the empire and readily conform to new and stricter controls. By 1760 smuggling had become a major American enterprise. Given that it was expensive to maintain revenue cutters and other patrol vessels along a thinly populated American coast filled with many bays, inlets, and rivers in which vessels could hide themselves, the British had found it far from cost-effective to try to enforce navigation laws. In 1761 the British began to reinforce writs of assistance, laws that granted customs officials the authority to conduct random searches of property to seek out goods on which required duties had not been paid, not only in public establishments but in private homes.

Representing New England’s merchants, attorney James Otis protested against these general warrants, proclaiming that “a man’s house is his castle,” and that violating its sanctity was a “wanton exercise” of power.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763.

In 1763 the British took another fateful step. Understandably wishing to reduce the cost of maintaining its empire, the British felt that if the North Americans would not interfere with the Indians, guarding of the frontiers would be less demanding and far less costly. Thus in 1763 a royal proclamation was issued that reserved all of the western territory between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi for use by the Indians. The colonists, now that the French were no longer present to rile and equip the Indians, saw the vast open reaches beyond the mountains as greener pastures to which they were entitled. The proclamation was thus seen as high-handed and uncalled for. Between 1763 and 1766 Pontiac's Rebellion took place in the Great Lakes region. The Indian tribes in that area were unhappy with British policies in the Great Lakes region at the end of the Seven Years' War. They occupied a large number forts controlling the waterways involved in trade with Great Britain.

1764. The North American Revenue (Sugar) Act and the Currency Act.

The next step was the “Sugar” Act of 1764, and it quickly became apparent that the purpose of the act was to extract revenue from America. The Molasses Act of 1733 had placed a tax of six pence per gallon on sugar and molasses imported into the colonies. In 1764 the British lowered the tax to three pence, but now decided to enforce it. In addition, taxes were to be placed on other items such as wines, coffee, and textile products, and other restrictions were applied. The Act authorized Vice Admiralty Courts, which took the place of jury trials; judges terms were changed to “at the pleasure of the Crown”; and so on.

The Currency Act of 1764 prohibited “legal tender” paper in Virginia, which reduced the circulation of paper money in America, further burdening the colonies, which were always short of hard currency. The British enforcement of the “Sugar” or “Molasses” Act quickly cut into the economic welfare of the colonies by causing a slump in the production of rum. Americans were becoming increasingly leery of what they perceived as British attempts to milk more profits from the colonies. Meetings were called to protest the law, and the idea of “taxation without representation” began to take shape.

The Stamp Act Crisis, 1765

“It should be your care, therefore, and mine, to elevate the minds of our children and exalt their courage; to accelerate and animate their industry and activity; to excite in them an habitual contempt of meanness, abhorrence of injustice and inhumanity, and an ambition to excel in every capacity, faculty, and virtue. If we suffer their minds to grovel and creep in infancy, they will grovel all their lives.” —John Adams, Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law, 1756

Although the American colonists were unhappy with the restrictions on trade and various import and export duties, they were not necessarily philosophically opposed to the right of the British to control trade, especially as they found it easy to avoid the attendant duties. The Stamp Act of 1765, however, opened a new door. John Adams and others believed that the Stamp Act was the point at which the real American Revolution began, in “the hearts and minds” of the people, as Adams put it. The Stamp Act caused a furious storm in the streets of New York, Boston, Richmond, and elsewhere.

The Act required that revenue stamps be placed on all newspapers, pamphlets, licenses, leases, and other legal documents, and even on such innocuous items as playing cards. The revenue from the act, which was to be collected by colonial American customs agents, was intended for “defending, protecting and securing” the colonies. The use of the revenue did not bother anyone; the fact that it was being collected solely for revenue purposes without the consent of the colonies bothered all kinds of people, especially those who conducted business of any kind. Those who objected to the act included journalists, lawyers, merchants, and other businessmen, men likely to be community leaders, and well-known public figures such as James Otis, John Adams, and wealthy businessman John Hancock.

The protests soon moved beyond the mere voices of opposition. Men selected to be collectors of the new taxes were openly threatened with violence, and many resigned their posts before they had collected anything. Associations were formed to encourage nonimportation (boycotts) of British goods. Colonial legislatures nullified the act, and shipments of stamps were destroyed. Sons of Liberty organizations and committees of correspondence were formed to create a feeling of solidarity among the afflicted.

In Virginia, resolutions were adopted denouncing taxation without representation. The colonists were not denying their status as British citizens subject to the Crown, but rather were expressing their rights as British citizens not to be taxed without their consent through duly appointed or elected representatives. The Massachusetts Assembly called a Stamp Act Congress for October 1765 in New York City. Among the resolutions passed by the Congress were the following:

- That His Majesty’s subjects in these colonies, owe the same allegiance to the Crown of Great-Britain, that is owing from his subjects born within the realm, and all due subordination to that august body the Parliament of Great Britain.

- That His Majesty’s liege subjects in these colonies, are entitled to all the inherent rights and liberties of his natural born subjects within the kingdom of Great-Britain.

- That it is inseparably essential to the freedom of a people, and the undoubted right of Englishmen, that no taxes be imposed on them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their representatives.

- That the people of these colonies are not, and from their local circumstances cannot be, represented in the House of Commons in Great-Britain.

- That the only representatives of the people of these colonies, are persons chosen therein by themselves, and that no taxes ever have been, or can be constitutionally imposed on them, but by their respective legislatures.

Benjamin Franklin was invited to speak in Parliament, and he laid out the colonial objection to taxes. Although the British realized that they had blundered into a minefield, they still sought to assert the right of the British government to govern the colonies as it saw fit. The British followed a principle of “virtual representation,” which meant that Parliament governed for the entire empire and noted that there were areas of England itself that were not represented in Parliament (to which the colonists replied that they should be). The theory was that “what’s good for the British empire is good for all its parts.”

In truth the colonists benefited greatly from being part of the British Empire. They could trade freely within the entire British colonial system, which meant worldwide ports were open to them. Furthermore, when they traveled outside the trade routes of the empire itself, they were always protected by the mighty Royal Navy. Flying the British flag, the colonists knew that they had a staunch protector when they ventured into foreign waters. Unfortunately, the British focused their attention on the duties of the colonists rather than on the benefits they enjoyed from their position within the British Empire.

The Declaratory Act of 1766.

Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, in part because their constituents in England quickly perceived that if Parliament could extract revenue from the colonists with a free hand, they could also do so at home. But as a warning to the colonies, they passed the Declaratory Act of 1766 on the same day. The Act stated that Parliament “had hath, and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America ... in all cases whatsoever.” Although the Americans had won something of a victory in the repeal of the Stamp Act, they were soon to find that British attempts to raise revenue would not cease.

The Townshend Acts of 1767-1768.

Matters continued to escalate between Parliament and the colonies, and sooner or later they were bound to reach a breaking point. Instead of being chastised by the protest over the Stamp Act, however, Parliament continued to assert its will over the colonies, which only made things worse. In 1767 Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend decided that because the colonists had raised objections to the Stamp Act, he would reassert Great Britain's right to impose new taxes on imported goods. The Townshend duties placed taxes on glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea, all of which had to be imported from Britain. The Acts also imposed rules intended to tighten collection of customs duties in America and to place restrictions on New York for having failed to obey the Quartering Act of 1765. There were more protests against the Townshend duties, and a non-importation agreement was reached in 1768. That created more difficulties for parliament because British merchants realized that they would suffer from the actions that Parliament was taking against the colonies.

In response to the Townshend Duties John Dickinson wrote the following in his Letters from an American Farmer. Referring to claims of a material difference between the Stamp Act and the Townshend Duties and that the new taxes were therefore justified, Dickinson said: “That we may be legally bound to pay any general duties on these commodities relative to the regulation of trade, is granted; but we being obliged by the laws to take from Great-Britain, any special duties imposed on their exportation to us only, with intention to raise a revenue from us only, are as much taxes, upon us, as those imposed by the Stamp Act.”

Dickinson’s point was followed by a new round of actions by the colonials to thwart British intentions. For some time among the more prosperous folk of American cities, it had been fashionable for women to support the latest fashion from London. Now politics intruded upon the fashion world, as the wearing of homespun became de rigueur. To show one’s patriotism, in other words, women were to take the lead in providing clothing that was American made, not British made, a small but significant step in introducing American women into the political system. In Boston, agents attempting to collect the new duties were met with physical opposition, which led to the dispatching of two British regiments to Boston to maintain law and order.

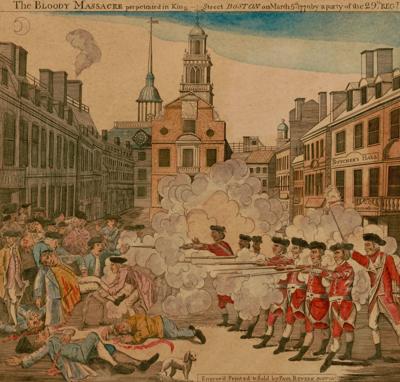

The “Boston Massacre”

The presence of Redcoats in Boston, rather than calming the troubled waters, only roiled them further. The typical British soldier of the time was a rough-hewn sort accustomed to taking advantage of his position to further his personal fortunes. British soldiers sought employment during their off-duty hours, and being unmarried males, they were accustomed to free-spirited entertainments. The citizens of Boston, concerned for the safety of their daughters in the presence of these ruffians, as they saw them, often exchanged taunts and insults with the hated soldiers. On the evening of March 5, 1770, unsurprisingly, violence erupted.

The presence of Redcoats in Boston, rather than calming the troubled waters, only roiled them further. The typical British soldier of the time was a rough-hewn sort accustomed to taking advantage of his position to further his personal fortunes. British soldiers sought employment during their off-duty hours, and being unmarried males, they were accustomed to free-spirited entertainments. The citizens of Boston, concerned for the safety of their daughters in the presence of these ruffians, as they saw them, often exchanged taunts and insults with the hated soldiers. On the evening of March 5, 1770, unsurprisingly, violence erupted.

It began with a more or less rowdy mob taunting a group of soldiers guarding the Customs House. The colonists began throwing snowballs, some containing rocks, at the unfortunate soldiers, and threatening the Redcoats with clubs. An officer, Captain Preston, appeared and read the Riot Act (an actual document) to those causing the disturbance, ordering them to disperse. Tensions escalated, however, and someone shouted “Fire!” Weapons were discharged, and five Bostonians were killed, including Crispus Attucks, an escaped slave. In the aftermath it was not clear who had shouted the word that caused the soldiers to discharge their rifles, but in any case the damage was done.

Captain Preston and the eight soldiers were tried for murder, and their defender was none other than future American president John Adams. Adams made a lengthy summary speech addressing the testimony of eyewitnesses, after which he concluded:

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence: . . . if an assault was made to endanger their lives, the law is clear, they had a right to kill in their own defence.”

Captain Preston and most of the soldiers were acquitted. John Adams's defense of Captain Preston and the soldiers has often been held up as an example of the principle that the rule of law should rise above emotional responses to unpopular events.

The Gaspee Affair.

In 1772 in Rhode Island another event occurred that riled British authorities. Smuggling by American colonists had been a thorn in the side of British authorities for decades. Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island was suspected by the British of being a hotbed of smuggling activity and a haven for what they regarded as pirates. An arrogant British naval officer, one Lieutenant William Dudingston, sailed into Narragansett Bay aboard the customs schooner Gaspee to assist in the collection of revenue. His haughty attitude toward Rhode Islanders immediately made him an enemy of the people. In June of that year he chased a packet boat into the harbor but ran aground on a sand bar.

The local citizens were delighted at the opportunity to gain some revenge against the overbearing officer. An armed group of the local Sons of Liberty rowed out to the Gaspee, boarded the vessel and captured the lieutenant and his crew. They rowed him ashore and set fire to the revenue ship. Outraged British authorities formed a commission and vowed to punish the offenders by taking them back to Britain for trial. When British authorities made inquiries among nearby residents, however, they were met with stony silence. The event added fuel to the fire that had been smoldering in England against what was seen as the stubborn and unruly behavior of the American colonists.

The Gaspee Affair, as it became known, was followed by the revelation by Benjamin Franklin, at the time the colonial agent in England, of a letter from Thomas Hutchinson complaining about the unruly behavior of the citizens of Massachusetts. Governor Hutchinson's letterhead included the unfortunate claim that “there must be an abridgment of water called English liberties.” Franklin was assailed in speech before Parliament for leaking what was deemed a private letter, and London newspapers painted him as a villain. When reports of the “purloined letters” reached the colonies, it was chalked up as one more piece of evidence that the British had no respect for colonial rights.

The Boston Tea Party

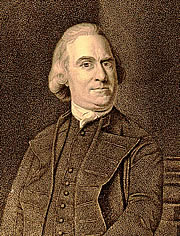

The next event in the drama, not surprisingly, once again took place in Boston under the leadership of Samuel Adams, a cousin of John Adams who was even more revolutionary than his less famous relative. The British East India Company found itself in dire financial straits and asked the British government to issue the company monopoly rights on all tea exported to the colonies. The company was also allowed to sell tea directly, bypassing merchants. The tea tax retained when the Townshend duties were repealed was still in force. The tea was consigned to merchants selected by the East India Company to be sold for profit. Although the price of tea would actually be lower under the act, the colonists nevertheless believed that the British actions were directed against them, even though the purpose of the act was to save the company. (It is safe to say that by that time, any action by the British that had a negative impact on the colonists was seen as a deliberate provocation.)

The next event in the drama, not surprisingly, once again took place in Boston under the leadership of Samuel Adams, a cousin of John Adams who was even more revolutionary than his less famous relative. The British East India Company found itself in dire financial straits and asked the British government to issue the company monopoly rights on all tea exported to the colonies. The company was also allowed to sell tea directly, bypassing merchants. The tea tax retained when the Townshend duties were repealed was still in force. The tea was consigned to merchants selected by the East India Company to be sold for profit. Although the price of tea would actually be lower under the act, the colonists nevertheless believed that the British actions were directed against them, even though the purpose of the act was to save the company. (It is safe to say that by that time, any action by the British that had a negative impact on the colonists was seen as a deliberate provocation.)

In Charleston, Philadelphia and New York, ships bearing East India Company tea were turned back, but in Boston Governor Hutchinson saw to it that the tea arrived in the harbor. On the night of December 16, 1773, Samuel Adams called a town meeting, where a resolution was passed urging the ships' captains to return to England. Governor Hutchinson refused to allow the Dartmouth, one of the tea ships, to leave the port. Later that evening a band of colonials disguised in Indian dress boarded the British ships and dumped thousands of pounds of tea into Boston harbor. It was clear that the act involved destruction of property, and the British ministry under Prime Minister Lord North could not afford to allow the act to go unpunished.

As mentioned above, the modern phenomenon known as the Tea Party Movement is patterned after the events of 1773. While the most obvious connection is the notion of protest against government action, the circumstances are only superficially similar. A modest tax on tea had been passed as part of the Townshend duties of 1867. The tax was retained when the Townshend duties were repealed, but the boycott on British goods was suspended. The purpose of the Tea Act of 1773 was to aid the East India Company, but the colonists perceived it as being directed against them, even though the Act resulted in a lower price of tea than previously. The Tea Party was retaliation against perceived wrong, but it did raise once again the issue of Parliament's right to tax the colonies without their consent.

The Coercive Acts

Parliament's response was five new laws—the “Coercive Acts”—that soon became known as the “Intolerable Acts,” which included the following:

• The Boston Port Bill closed the port of Boston until the tea was paid for, a questionable tactic as commerce in the city would become paralyzed.

• The Administration of Justice Act abolished local administration of justice and provided that the governor of Massachusetts could cause all trials to be conducted in that colony to be removed to Great Britain and heard under a British judge so that the result would favor the British.

• The Massachusetts Government Act virtually suspended the right of self-government in the Massachusetts colony by ensuring that the governor and all public officials would serve “at the pleasure of his Majesty.”

• The Quartering Act of 1765 was extended to require that troops be housed not only in public buildings, but in occupied private dwellings such as homes as well.

• The Quebec Act extended the boundaries of Quebec and guaranteed religious freedom to Canadians. Though not intended to be punitive, the measure fed into anti-Catholic sentiments.

The Boston Port Bill caused an immediate reaction, as it would cripple the economic life of the city. Many hundreds of workers would be affected, not just those responsible for destruction of the tea. The British hoped the act would isolate Boston's radicals and built respect for Parliament, but the opposite occurred. Sympathy for the beleaguered city spread quickly throughout New England and beyond. Committees of safety and correspondence were formed throughout the colonies to spread the news of what was perceived as tyrannical behavior by the British in punishing the city of Boston. Copies of the act were sent to the other colonies, where it was rejected, burned in effigy, and held up as proof of Parliament's attempt to subjugate the American colonies.

Requests of assistance from Boston were met by donations of food, livestock, clothing, and other necessities as well as money, though the last was often offered in meager sums, given that cash was a scarce commodity in all the colonies. Resistance to British authority was widespread. Reports from colonial governors and their assistants back to Lord Dartmouth, colonial secretary, indicated that colonists were refusing to report for jury duty, ignoring or harassing local colonial officials, and raising funds for support of their “suffering brethren in Boston.” Newspapers spread the word of the oppressive behavior, and instead of raising fears and other cities and towns that they would be subject to a similar fate, colonists rose and indignation against the policies of the mother country.

A growing sense of unity among the colonies led to more concrete actions: The First and Second Continental Congress

| American Revolution Home | The Continental Congresses | Updated May 21, 2020 |