The Roots of Progressivism

Copyright © 2005-6, Henry J. Sage

The Progressive Era is a widely recognized period in American history which is generally considered to have begun around 1896 to 1900 and to have ended with America's entry into the First World War in 1917. Since the intensity of progressive reform peaked during that time, the designation is appropriate. But in a larger sense, the reform impulse in America has been present even back into colonial times, and it certainly has continued well into the modern era and into the present. Few if any educated Americans would ever claim that this country has solved all its problems, provided a level playing field for all citizens and workers, or that our political system is free from corruption of one sort or another. Yet we still have a collective yearning to root out those things. The progressive beat goes on.

Thus the roots of American Progressivism are deep and wide, but the last few decades of the 19th century created new conditions that cried out for reform. As you will note elsewhere in these pages, the years between the end of the American Civil War and the turn of the century were characterized by what historian Page Smith has called the “war between capital and labor.” 9That idea is discussed in the previous section on the Gilded Age.) As millions of immigrants poured into the country, cities became crowded and unhealthy, working conditions grew evermore appalling, and the political powers were unwilling or unable to address the rapid economic and social changes brought about by the burgeoning industrial revolution in America.

The year 1896 marks the approximate beginning of the Progressive Era, but during the “reckless decade” of the 1890s the impulse for reform was driven by the Populist Party, which was made up of farmers, small businessmen and reform-minded leaders who were willing to confront the growing problems in the country. The situation was summarized, dramatically of course for its desired political impact, in the Populist Party platform, issued at its convention in Omaha in 1892, which read in part:

The conditions which surround us best justify our cooperation: we meet in the midst of a nation brought to the verge of moral, political, and material ruin. Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the legislatures, the Congress, and touches even the ermine of the bench. The people are demoralized; most of the States have been compelled to isolate the voters at the polling-places to prevent universal intimidation or bribery. The newspapers are largely subsidized or muzzled; public opinion silenced; business prostrated; our homes covered with mortgages; labor impoverished; and the land concentrating in the hands of the capitalists. The urban workmen are denied the right of organization for self-protection; imported pauperized labor beats down their wages; a hireling standing army, unrecognized by our laws, is established to shoot them down, and they are rapidly degenerating into European conditions. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of these, in turn, despise the republic and endanger liberty. From the same prolific womb of governmental injustice we breed the two great classes-tramps and millionaires.

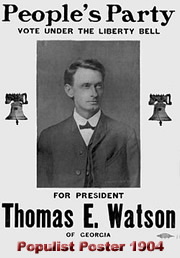

Even allowing for hyperbole, the Populist claim was essentially true. the Populist Party, like many American institutions at that time, was divided internally over issues of race, geography, economic orientation, and general political loyalty. Despite that, the Populists elected state and local officials, mostly in the South and Midwest, and Tom Watson, a Populist leader pictured at the left, served in the Georgia legislature, the United States House of Representatives, was nominated for vice president along with William Jennings Bryan in 1896, and ran for president in 1904. By pushing their political agenda, the Populists affected legislation in a limited way, although their national impact was restricted by the usual limitations on third parties.

Even allowing for hyperbole, the Populist claim was essentially true. the Populist Party, like many American institutions at that time, was divided internally over issues of race, geography, economic orientation, and general political loyalty. Despite that, the Populists elected state and local officials, mostly in the South and Midwest, and Tom Watson, a Populist leader pictured at the left, served in the Georgia legislature, the United States House of Representatives, was nominated for vice president along with William Jennings Bryan in 1896, and ran for president in 1904. By pushing their political agenda, the Populists affected legislation in a limited way, although their national impact was restricted by the usual limitations on third parties.

In their platform of 1892, the Populists laid out a program of reform designed to help the small farmer a small businessman and all those who saw themselves as victims of capitalist power. It is worth noting that in our current political environment, not only in the United States but across parts of Europe, populism has become an attractive feature used by political figures to focus on the needs of ordinary people. The Populist Party disappeared following the election of 1896, in which it endorsed the Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan, who had addressed populist concerns in his famous “Cross of Gold” speech. By tying themselves to a major party, however the Populists lost their unique identity.

Nevertheless, by the end of the Progressive Era in 1917, most of the concerns which the populists had raised in 1892 had been addressed by the federal government, albeit less than completely in a number of instances. Thus the roots of progressivism can be found in the widespread discontent in the nation around which the Populist Party emerged. Progressive leaders such as Robert M. La Follette, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and others, while perhaps not specifically attuned to the voice of the Populist Party itself, were nevertheless acutely aware of the conditions that demanded significant reform.

We should also keep in mind that the career of Franklin Roosevelt started during the Progressive Era, and the progressive ideas pursued by his cousin Theodore and President Woodrow Wilson, under whom he served for eight years, formed much of the basis of the New Deal program that FDR inaugurated upon becoming president in 1933. And as mentioned above, populist ideas remain alive and well today

| Progressive Home | Progressive Era | Updated January 28, 2018 |