We Americans tend to think of our Civil Rights movement as something that took place during the last half of the 20th century, an event focused on injustices visited upon our African American population. In fact, the struggle for the civil rights of Americans began during the colonial period, and its first manifestation was the protest movement that preceded and led into the American Revolution. Even at that time, however, the rights of African Americans were part of the story, as they petitioned the new American government on the issue of taxation without representation. Along with women's rights, gay rights and concerns of other minority populations, the movement goes on into the 21st Century.

We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

—United States Supreme Court, 1954

Brown v Board of Education of Topeka

One of the great paradoxes of American history lies in the fact that as the American colonists wrestled with the British Empire beginning about 1761, their rhetoric often asked the question, “Are we to remain free, or become slaves”? Even as they contemplated their own bondage to British authority, thousands of Americans existed under a harsh slave system. The founding fathers and mothers well understood that paradox and worried about its implications for the future. Even as the men in Philadelphia crafted the Constitution, one of them, George Mason of Virginia, himself a slave owner, predicted that “national calamities” would inevitably be the outcome of the “peculiar institution.” His prediction come true in April 1861 with the outbreak of civil war.

Following the “calamity”—Civil War—the Reconstruction period was focused on the issue of what to do with almost four million people who had been slaves all their lives and now were free. Thus the post-Civil War period saw the real birth of the modern civil rights movement. The post-Civil War amendments granted the fomer slaves not only freedom from bondage, but also citizenship and voting rights, but those rights were only partially realized at the time.

Now, in the dawn of the 21st century, new issues regarding civil rights confront us, often in unwelcome form, driven by religious intolerance, terrorism and the demands of emerging ethnic minorities seeking the freedoms that Americans have always cherished. If Nietsche was correct, the 21st Century may bring us all we can handle, and the struggles of the past may well pale by comparison. What is needed is clearly a growth of understanding and insight into the concerns of our neighbors in an ever shrinking world. Here again, we are not yet out of the woods. Much remains to be done.

We Americans tend to think of our Civil Rights movement as something that took place during the 20th century, an event focused on injustices visited upon our African American population. In fact, the struggle for the civil rights of Americans began during the colonial period; its first manifestation was the protest movement that preceded the American Revolution. Even then, however, the rights of African Americans were part of the story.

One of the great paradoxes of American history lies in the fact that as the American colonists wrestled with the British Empire, their rhetoric often asked the question, “Are we to remain free, or become slaves?” Even as they contemplated their own bondage to British authority, thousands of Americans existed in a harsh slave system. The founding fathers and mothers well understood that paradox and worried about its implications for the future. Even as the men in Philadelphia crafted the Constitution, George Mason of Virginia, himself a slave owner, predicted the “national calamities” that would inevitably be the outcome of the “peculiar institution.”

Following that “calamity”—the Civil War—the Reconstruction period focused on the issue of what to do with almost four million people who had been slaves all their lives and now were free. Thus the post-Civil War period saw the real birth of the modern civil rights movement.

You will recall from your reading about Reconstruction that the period was a time of progress and hope as well as a time of repression and violence. The federal government, led by radical Republicans in Congress, pushed hard to expand rights for freedmen, granting them citizenship and voting rights through constitutional amendments. The Freedmen’s Bureau helped provide educational opportunities for blacks and assisted them in developing economic self-sufficiency. For a time, things looked up, but many—including even sympathetic supporters of black progress—felt that Congress moved too far, too fast. A white backlash occurred in the South, and much of the progress made by 1877 was reversed by 1900. The groundwork for the later civil rights movement had been laid, however, although further progress was all but invisible until after World War II.

Still, small steps were made from time to time. Even as the 1896 Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson established the doctrine of “separate but equal,” Justice John Marshall Harlan called that doctrine “pernicious” in his dissent in the case. Only the most blind of observers could fail to see that even if the doctrine were accepted in theory, conditions for blacks were never equal in practice. Whether it was “white” and “colored” restrooms in bus depots and railroad stations, segregated elementary and high schools, or public enterprises such as hotels and restaurants, facilities for blacks were almost always inferior, generally widely so.

Slowly, the doctrine began to unravel in education. In higher education, southern states generally excluded black students from admission, but sometimes compensated by providing tuition for them to attend universities in the North. In a 1938 case in which a black student was denied entrance to the University of Missouri Law School, the student pled his case on the grounds that he wanted to study Missouri law, and no other law school taught Missouri law; the courts directed that he be admitted.

In 1950 the case of McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents involved a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma. The university admitted the student to the graduate program but denied him the right to live in a dormitory, sit in the library or eat in the dining hall with white students. The court decided that since graduate students often discuss their course work outside the classroom in the dining hall or dormitory, he could not pursue his education while thus separated. The case of Sweatt v. Painter arose when the University of Texas law school decided to create a separate law school for a single black student; the court quickly dismissed that notion because the history, prestige, faculty, and resources of the regular law school were far beyond anything that could be created for a single student. In other words, the court recognized intangibles as part of “separate but equal.” These two cases showed that the concept of separate but equal stood on increasingly shaky ground; it was bound to fall when the right case came along.

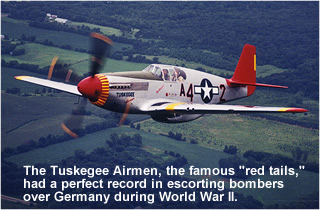

World War II also provided a backdrop for advances in civil rights. Thousands of black soldiers, sailors and airmen served with distinction during the Second World War, sometimes in segregated organizations. For example, the “Tuskegee Airmen,” provided fighter cover for bombing attacks on the homeland of Germany flown from Italy. Their record of effectiveness was unparalleled through the entire war. In another illustration, a tank battalion of black troops was one of the first American units to uncover a German concentration camp where Jews had been victimized. Again and again black men proved their military prowess, and at the conclusion of the war they were reluctant to be relegated to second-class status at home.

World War II also provided a backdrop for advances in civil rights. Thousands of black soldiers, sailors and airmen served with distinction during the Second World War, sometimes in segregated organizations. For example, the “Tuskegee Airmen,” provided fighter cover for bombing attacks on the homeland of Germany flown from Italy. Their record of effectiveness was unparalleled through the entire war. In another illustration, a tank battalion of black troops was one of the first American units to uncover a German concentration camp where Jews had been victimized. Again and again black men proved their military prowess, and at the conclusion of the war they were reluctant to be relegated to second-class status at home.

See Video Clip from "Tuskegee Airmen" (Apologies for the commercial)

In 1946 the courts disallowed discrimination on interstate buses, and in 1948 restrictive covenants in real estate transactions (often directed at people of the Jewish faith) were challenged. In 1948 President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which stated that the president’s policy would forthwith establish “equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.” He also ordered an end to discrimination within the federal Civil Service.

The Film Gentlemen’s Agreement (1947) explored the issue of anti-Semitism in America. Considered courageous at the time, it preceded the civil rights revolution by about a decade.

By 1954 a number of Supreme Court cases had whittled away at additional white supremacy laws and had shown the untenable nature of such doctrines. The Texas primary cases over the decades from 1927-1953 required that all citizens be permitted to vote in primary elections, especially in places where a virtual one-party system existed. In other cases attempts to legally restrict African Americans from professional schools were voided as violations of the Fourteenth Amendment. In the 1940s the federal government had also made moves to end discriminatory practices. In 1946 President Truman created a presidential Committee on Civil Rights, and at the Justice Department a Civil rights Division was established, as was a Fair Employment Practices Commission.

The great landmark event of the modem movement was the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which reversed Plessy v. Ferguson. The case was brought by the N.A.A.C.P. as the culmination of numerous attempts to attack segregated school systems in different states, and President Eisenhower worked behind the scenes with the court to make sure that the decision would be unanimous. In 1954 the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren declared unanimously that segregation in public education did not constitute equal protection under the law. The initial decision did not explain how desegregation was to be achieved. The case was sent back to the state courts and was heard again in 1955. In the second case, known as Brown II, the Supreme Court directed state courts to resolve integration issues locally on an equitable basis, and required “good faith” implementation with a “prompt and reasonable start” on racially non-discriminatory bases … with all deliberate speed.” The Court also extended the principle to all public facilities.

The great landmark event of the modem movement was the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which reversed Plessy v. Ferguson. The case was brought by the N.A.A.C.P. as the culmination of numerous attempts to attack segregated school systems in different states, and President Eisenhower worked behind the scenes with the court to make sure that the decision would be unanimous. In 1954 the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren declared unanimously that segregation in public education did not constitute equal protection under the law. The initial decision did not explain how desegregation was to be achieved. The case was sent back to the state courts and was heard again in 1955. In the second case, known as Brown II, the Supreme Court directed state courts to resolve integration issues locally on an equitable basis, and required “good faith” implementation with a “prompt and reasonable start” on racially non-discriminatory bases … with all deliberate speed.” The Court also extended the principle to all public facilities.

The Brown decision was in reality both a beginning and an end. The case did close the door on the legality of the doctrine of separate but equal, but it did bring forth yet another counterrevolution. Long time Virginia political leader, Senator Harry Flood Byrd, introduced the term “massive resistance” to describe what those opposed to integration had in mind. Not long after the second Brown decision, 101 members of Congress signed a “Southern manifesto,” under which they promised to oppose integration by all legitimate means. Although the second Brown decision had called for speedy integration, the process was painfully slow, and by 1957 less than 700 of over 3000 Southern school districts had begun to integrate their schools. Many white parents organized private schools as an alternative to sending their children to integrated public schools, and state funds were often diverted to support those schools. One county in Virginia closed its public schools altogether and established private schools, the tuition for which would be the same as the portion of taxes formerly paid to support public schools.

In 1957 Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, became the focus of an integration attempt. Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas called out the Arkansas National Guard in order to keep nine black students from attending Central High School in accord with a federal court order. A confrontation between President Eisenhower and Governor Faubus led to the removal of the National Guard, but the students were unable to enter the school because they were faced by an angry white mob. Reluctantly, President Eisenhower ordered a thousand United States paratroopers to Little Rock to protect the students and placed the Arkansas National Guard into federal service. The soldiers remained on school grounds throughout that year. A year later Governor Faubus closed the Little Rock schools, and they were not reopened until 1959. After further disputes and attempts to stop integration, the Supreme Court ruled that the violence was “directly traceable” to the governor of Arkansas and federal laws could not be nullified, directly or indirectly.

In 1957 Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, became the focus of an integration attempt. Governor Orval Faubus of Arkansas called out the Arkansas National Guard in order to keep nine black students from attending Central High School in accord with a federal court order. A confrontation between President Eisenhower and Governor Faubus led to the removal of the National Guard, but the students were unable to enter the school because they were faced by an angry white mob. Reluctantly, President Eisenhower ordered a thousand United States paratroopers to Little Rock to protect the students and placed the Arkansas National Guard into federal service. The soldiers remained on school grounds throughout that year. A year later Governor Faubus closed the Little Rock schools, and they were not reopened until 1959. After further disputes and attempts to stop integration, the Supreme Court ruled that the violence was “directly traceable” to the governor of Arkansas and federal laws could not be nullified, directly or indirectly.

Another milestone occurred in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955 when Rosa Parks, a black working woman and member of the N.A.A.C.P., refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. Black citizens of Montgomery quickly organized a boycott of the bus system and arranged for carpools and other expedients to get black men and women to and from their workplaces. Martin Luther King, Jr., pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, helped organize the boycott and quickly rose to prominence within the civil rights movement. In 1956 a lower court ruled that “the separate but equal doctrine can no longer be safely followed as a correct statement of the law.” The Supreme Court let the decision stand.

In 1957 the first civil rights act since the Reconstruction period was passed. The act established the civil rights commission and a civil rights division within the Department of Justice, which had the power to prevent interference with the people’s right to vote. Civil rights activists continued to challenge policies of segregation. Four black college students conducted a sit in at a lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, and the movement quickly spread. In 1961 freedom riders began moving into the South to test the federal court decision that made segregation on trains and buses illegal. As the 1960s progressed, marches and demonstrations spread across the South, and black and white civil rights leaders applied pressure for more rapid changes.

Violence often accompanied these movements, and a number of black demonstrators gave their lives in fighting for their civil rights. Television viewers across the country and in other nations saw images of peaceful demonstrators being attacked with dogs, clubs, fire hoses and tear gas. Riots erupted in Los Angeles, Detroit, Newark, Washington and other cities as frustration spread outside the South. Clearly, Civil Rights had become a national issue.

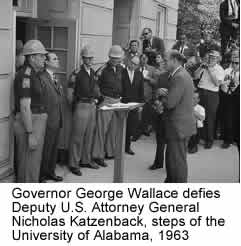

When President Kennedy moved into the White House in 1960, he faced difficulties with a Democratic Congress strongly guided by conservative Southern Democrats. Not as heavily committed to the cause of civil rights as Attorney General Robert Kennedy or his vice president, Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy was nevertheless moved to act after Martin Luther King was jailed for his protest activities in Birmingham, Alabama. He told aides to prepare a civil rights bill. On the evening of the day when Alabama Governor George Wallace had tried to block admission of a black student to the University of Alabama, Kennedy went on television to support the bill. In his speech he said:

The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who will represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?

In August 1963 civil rights leader A. Phillip Randolph organized a March on Washington in support of civil rights legislation and jobs. Afraid of further violence, Kennedy and his aides persuaded black leaders to be moderate in their demands. The march, which was limited to one day, culminated in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The civil rights act proposed by President Kennedy did not, however, pass during his brief term.

Major Civil Rights Milestones of the 1950s and 1960s

The Civil Rights Act (1957) In 1957 the Southern Christian Leadership Conference was formed. Also in that year a Civil Rights Act proposed by President Eisenhower was passed, the first such act since Reconstruction. The act established the Civil Rights Commission and a Civil Rights Division within the Justice Department. Under the new law the Attorney General was authorized to enforce the right to vote, and the act also reinforced laws that made interfering with voting illegal.  Senator J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina filibustered against the act in the Senate and set a filibustering record of 24 hours, 18 minutes.

Senator J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina filibustered against the act in the Senate and set a filibustering record of 24 hours, 18 minutes.

In 1958 the Supreme Court heard the case of the N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama. Alabama had attempted to inhibit the activities of the N.A.A.C.P., and ordered them to produce various records. The Alabama chapter of the N.A.A.C.P. refused to submit its membership lists to the state on Constitutional grounds and was fined $100,000. The Supreme Court disallowed the Alabama action. Justice Harlan argued that “immunity from state scrutiny … [comes] within the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment.” The N.A.A.C.P. therefore did not have to disclose its list of members and had a constitutional right to protect its membership.

In 1960 a new Civil Rights Act strengthened the 1957 Act. It established federal inspections of local voter registration polls and introduced penalties for anyone obstructing a person’s attempt to register to vote or actually vote. Many different cases made their way through state and federal courts over the years, as they struggled to find the exact meanings of the new laws. Questions about jurisdiction, the extent to which states were required to be aggressive in enforcing laws, and other related issues were up in the air for years.

Baker v. Carr, 1962

This case arose in Tennessee and reached the Supreme Court in 1962. In 1901 the State of Tennessee passed a law apportioning seats in the state General assembly among the state’s counties. Growth in the population of Tennessee led to an unfair distribution of seats in the assembly, as population shifts since the 1901 apportionment were not reflected. A group of Tennessee voters brought the case because they felt they had suffered a “debasement of their votes,” and were thus denied the equal protection of the laws guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment. In this case the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts did have jurisdiction because it was a constitutional issue.

The subsequent cases of Gray v. Sanders, a 1963 Georgia case, and the 1964 Alabama case, Reynolds v. Sims, the Supreme Court followed the precedent of Baker andheld that improper or unfair apportionment was unconstitutional. In Gray the court stated that, “The concept of political equality...can mean only one thing—one person, one vote." The Court maintained in those cases that citizens’ voting rights were denied if their votes were diluted. Apportionment should be based on population, not other factors such as geography, history or economic structure. State legislatures should be represented as nearly as practicable on the basis of equal population, meaning that the vote of every person should be equal in value to the vote of every other person. After Chief Justice Warren left the Court, he asserted that Baker v. Carr and the subsequent line of cases were among the most important cases the Supreme Court ever decided.

The subsequent cases of Gray v. Sanders, a 1963 Georgia case, and the 1964 Alabama case, Reynolds v. Sims, the Supreme Court followed the precedent of Baker andheld that improper or unfair apportionment was unconstitutional. In Gray the court stated that, “The concept of political equality...can mean only one thing—one person, one vote." The Court maintained in those cases that citizens’ voting rights were denied if their votes were diluted. Apportionment should be based on population, not other factors such as geography, history or economic structure. State legislatures should be represented as nearly as practicable on the basis of equal population, meaning that the vote of every person should be equal in value to the vote of every other person. After Chief Justice Warren left the Court, he asserted that Baker v. Carr and the subsequent line of cases were among the most important cases the Supreme Court ever decided.

In 1962 James Meredith integrated the University of Mississippi, and in the following year massive demonstrations across the South culminated in August with Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial on the Mall in Washington. Under President Lyndon Johnson additional Civil rights legislation was passed, and new, more militant black voices were heard. In New York City in 1965 Malcolm X was assassinated, and Martin Luther King led the famous Selma to Montgomery freedom march. When African American students attempted to enter the University of Alabama in 1965, Alabama Governor George Wallace invoked the notion of “interposition,” claiming the right of state authorities to interpose state sovereignty between the federal government and residents of their state. Additional civil rights cases examined mote then just new civil rights laws; one case went back to the 1866 Trumbull Civil Rights Act and the Thirteenth Amendment to declare that refusing to sell real estate to blacks constituted a “badge of slavery,” which Congress had the power to define.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a major achievement of President Lyndon Johnson. The act prohibited unfair application of voter registration requirements, but it did not abolish literacy tests, which were sometimes used to disqualify blacks and poor white voters. The act also outlawed discrimination in hotels, motels, restaurants, theaters, and all other public establishments involved in interstate commerce; however, the act exempted private clubs without defining “private,” thereby allowing a loophole. Title III of the Act authorized the Attorney General to bring suits to force desegregation in schools, but the act did not authorize busing as a means of overcoming segregation based on residence. Title V made discrimination in employment in any business exceeding 25 people illegal and created an Equal Employment Opportunities Commission. Title VII prohibited discrimination based on gender.

The National Voting Rights Act of 1965 made it illegal to require that voters in the United States take literacy tests to qualify to register to vote, and it provided for federal registration of voters in areas that had less than 50% of eligible minority voters registered. The act also provided for oversight of voter registration by the Department of Justice. It further required Justice Department approval for changes in voting law in districts that had used a “device” to limit voting and in which less than 50% of the population was registered to vote in 1964.

The 1968 Civil Rights Act expanded previous acts and prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, and sex. It also provided protection for civil rights workers.

By the late 1960s various states were still struggling with integration, and the courts became less and less sympathetic to explanations of why it was not proceeding faster. By the 1970s the courts were demanding “extreme measures” a “necessary evil” when all other things were not equal. The extreme measures included such actions as forcing cities to build new schools or to raise taxes to buy buses to facilitate integration. At the same time the Courts began to recognize that not all segregation was forced or created by law; some rulings were sympathetic to cities where good faith efforts to integrate had not been able to keep pace with voluntary migration. The courts reasoned that the presence of some nearly all black or all white schools did not necessarily indicate enforced segregation.

Now, early in the 21st century, new issues regarding civil rights confront us, often in unwelcome forms, driven by religious intolerance, terrorism and the demands of emerging ethnic minorities seeking the freedoms that Americans have always cherished. If Nietsche was correct, the 21st Century may bring us all we can handle, and the struggles of the past may well pale by comparison. What is needed is clearly a growth of understanding and insight into the concerns of our neighbors in an ever shrinking world. Here again, we are not yet out of the woods. Much remains to be done.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and

Jackie Robinson at the

Baseball Hall of Fame

Cooperstown, New York, 1962

Documents and Resources

- The National Organization for Women Founding Document

- Brown v Board of Education of Topeka

- Martin Luther King: Letter from a Birmingham Jail

- Martin Luther King: "I Have a Dream"

- Voting Rights Act of 1965

- President Johnson's Speech on the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- Excerpt from Baker v. Carr, 1962

- Brown v. Board of Education NPS Museum

Additional Civil Rights links:

- The National Organization for Women Founding Document

- President Truman Orders Integration of the Armed Forces

- Brown v Board of Education of Topeka

- Martin Luther King: Letter from a Birmingham Jail

- Martin Luther King: "I Have a Dream"

- The King Papers at Stanford University

- Civil Rights Act of 1957

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Voting Rights Act of 1965

- Excerpt from Baker v. Carr, 1962