Korea, The Forgotten War

General Douglas MacArthur is one of America's most colorful historic characters. Son of a career army officer, he served over 50 years in the Army and fought in three wars. In 1935 he retired as Chief of Staff of the Army and went to the Philippines, where he took over command of all American and Philippine military forces during the years leading up to World War II. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor they invaded the Philippines. MacArthur was forced to abandon the islands; he retreated to Australia and assumed command of all forces in the Southern Pacific area. From there MacArthur led U.S. forces back through Indonesia and retook the Philippines late in the war. Following the reduction of Okinawa, he and the Navy and Marine forces under Admiral Nimitz began planning the invasion of Japan. Before that could occur, the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought about the Japanese surrender.

As the senior representative of the Allied Powers, MacArthur made a memorable speech about the horrors of war as he accepted the formal Japanese capitulation aboard the U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay in September, 1945. He stayed on as the senior allied occupation officer, and became virtually the acting emperor of Japan. He was a strong force in converting Japan into a modern, democratic state, and was even involved with writing the pacifistic Japanese Constitution. Most Japanese admired MacArthur and were gratified by his moderate, even-handed treatment of the Japanese people during the postwar years. He was truly a benevolent dictator.

(When this author asked a student who was raised in Japan what her countrymen and women thought of MacArthur, she answered, “They thought he was a god.”)

The Korean Peninsula had been a colony of Japan until World War II. In 1945 it was divided at the 38th parallel into two nations. At that time the United States and the Soviet Union jointly administered Korea in a manner similar to the disposition of occupied Germany at the time. Both nations had occupying forces in Korea, the Soviets in the North, Americans in the South. The North Korean government was Communist, the South Korean government non-communist and quasi-democratic, and both claimed sovereignty over the entire peninsula. The situation also resembled what would ensue in Vietnam after the French were defeated in 1954.

In 1949, after American educated strongman Syngman Rhee was elected President of the Republic of Korea (South Korea), the United States withdrew its occupying forces, except for a small advisory command. Soviet forces had withdrawn from the North in 1948. In 1950 North Korean Communist leader Kim Il-sung met with Soviet and Chinese Communist leaders and proposed to take over all of Korea by force. He met no objections from either nation and was offered their support. China repatriated 50,000 Korean soldiers who had fought for the Communists in China’s Civil War, and they became an important element of the North Korean People’s Army. Thus the struggle for control of Korea broke out when the North Koreans crossed the 38th parallel in force in 1950.

War Breaks Out. In June, 1950, North Korean troops surged across the border into South Korea, triggering the first major confrontation between the forces of the communist and non-communist worlds. The United States, which had occupied South Korea as part of the post-war administration of former Japanese colonies, became immediately involved in the war. Critics of American foreign policy claimed that when the Truman administration adopted its containment policy, the theoretical line drawn around areas that would be protected against communist aggression failed to include Korea. In addition, because the U.S. was preoccupied with affairs in Europe as well as rebuilding Japan on a democratic footing, North Korea’s Kim Il-sung and his Chinese and Soviet counterparts felt that the United States would not defend Korea. President Truman, however, contradictory to what others might have believed, decided immediately that, in keeping with his containment policy, the United States would come to the aid of South Korea. He appealed immediately to the United Nations for support, and was rewarded with a unanimous vote in the UN Security Council calling for a military defense of the Republic of Korea. For the first time, an international body voted to oppose aggression by force.

War Breaks Out. In June, 1950, North Korean troops surged across the border into South Korea, triggering the first major confrontation between the forces of the communist and non-communist worlds. The United States, which had occupied South Korea as part of the post-war administration of former Japanese colonies, became immediately involved in the war. Critics of American foreign policy claimed that when the Truman administration adopted its containment policy, the theoretical line drawn around areas that would be protected against communist aggression failed to include Korea. In addition, because the U.S. was preoccupied with affairs in Europe as well as rebuilding Japan on a democratic footing, North Korea’s Kim Il-sung and his Chinese and Soviet counterparts felt that the United States would not defend Korea. President Truman, however, contradictory to what others might have believed, decided immediately that, in keeping with his containment policy, the United States would come to the aid of South Korea. He appealed immediately to the United Nations for support, and was rewarded with a unanimous vote in the UN Security Council calling for a military defense of the Republic of Korea. For the first time, an international body voted to oppose aggression by force.

President Truman then ordered American naval and air forces to begin supporting the South Korean army. When it became apparent that the North Korean army could not be stopped by naval and air support alone, the President made the decision to commit ground forces to Korea. As the Security Council resolution had called for all nations with adequate military forces to contribute to South Korea’s defense, other nations such as Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia prepared to send military units to Korea. The United States, however assumed the major share of the burden of fighting the Korean War. President Truman named General Douglas MacArthur, America’s supreme commander in the Far East, commander of all forces to be engaged in Korea.

As Commander of all United Nations forces, General MacArthur immediately dispatched available ground units to Korea. Having been involved only in occupation duty since 1945, however, the American troops were ill prepared and ill equipped for combat against a well-trained army. Sent to Korea piecemeal, they, along with the South Koreans, were soon driven into a defensive perimeter around the South Korean port of Pusan, and for a while it looked as though North Korea would gain firm control of the entire nation. MacArthur visited the American troops in the Pusan perimeter and told their commanding general that his men would have to hold on while MacArthur prepared a countermove. If they were driven off or captured, retaking the peninsula would be an extremely difficult task.

Back in Japan General McArthur and his staff examined their options and came up with a bold proposal, which he submitted to the Joint Chiefs of Staff for approval. MacArthur’s plan called for an amphibious invasion of South Korea at the port of Inchon, not far below the 38th parallel. It was a daring move, as the attack would fall well behind North Korean lines. A variety of factors helped make MacArthur’s surprise move an unqualified success.

First, Inchon was an unlikely site for an invasion because of its high tidal swings, meaning that the enemy would not expect a landing there. Second, the geography of South Korea meant that the North Korean supply lines could be severed  with a quick strike inland from Inchon. In addition, Inchon was near the capital of Seoul and Kimpo airfield, the capture of which would be valuable. The First Marine Division under the command of Major General Oliver P. Smith and the 7th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General David G. Barr, conducted the landing, successfully capturing Seoul and Kimpo airfield in the process. The North Korean army, its supply lines severed, fell back in disarray across the 38th parallel. The breakout of American and Korean forces from Pusan soon followed.

with a quick strike inland from Inchon. In addition, Inchon was near the capital of Seoul and Kimpo airfield, the capture of which would be valuable. The First Marine Division under the command of Major General Oliver P. Smith and the 7th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General David G. Barr, conducted the landing, successfully capturing Seoul and Kimpo airfield in the process. The North Korean army, its supply lines severed, fell back in disarray across the 38th parallel. The breakout of American and Korean forces from Pusan soon followed.

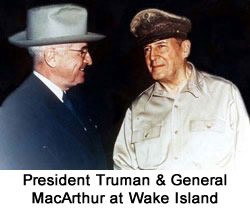

As American naval air and ground units entered the fray, and as the South Korean Army pulled itself together, the UN forces pursued the North Korean Army across the border. South Korea was once again secure. It does not go too far to claim that at that juncture, the Korean War had been won—the invasion had been repelled. General MacArthur chose to push the North Korean army back toward the Chinese border, however, feeling that China would not dare to intervene in the conflict. In a meeting with President Truman at Wake Island, he assured his commander-in-chief that Chinese intervention was unlikely. President Truman was aware that China had threatened to intervene in Korea, communicating their intent via neutral embassies. Truman felt the Chinese were bluffing. Both he and General MacArthur were wrong.

In November 1950 on Thanksgiving Day, a huge Chinese army swept across the border and soon drove the Americans back in the direction from which they had come. Part of that painful withdrawal included the movement of the First Marine  Division and the Seventh Army Division from the Chosin Reservoir area, a fighting withdrawal that took place in bitter cold weather. “Frozen Chosin” became an epithet for the painful process of extricating American troops from what had seemed a virtual death trap. The gains that had been made at great sacrifice were mostly lost, as the North Korean army once again crossed into South Korea and recaptured the capital of Seoul.

Division and the Seventh Army Division from the Chosin Reservoir area, a fighting withdrawal that took place in bitter cold weather. “Frozen Chosin” became an epithet for the painful process of extricating American troops from what had seemed a virtual death trap. The gains that had been made at great sacrifice were mostly lost, as the North Korean army once again crossed into South Korea and recaptured the capital of Seoul.

To bolster his defenses General MacArthur sought permission to attack Chinese forces across the Yalu River in Chinese territory. He wanted hit the Chinese army in their sanctuary. He believed that attacking bases from which the Chinese army was being supplied was a key to defeating them in South Korea. The Truman administration, not wishing to escalate the crisis nor provoke a full, all-out war between United States and Communist China, restricted MacArthur's movements to the territory of North Korea. When informed that he might bomb the southern half of bridges over the Yalu River, MacArthur fumed, “In all my years of military service I have never learned how to bomb half a bridge!”

Uncomfortable with the Truman administration's policies, General MacArthur openly criticized his commander-in-chief and sent a letter to a Republican congressman which was released to the public. After consultation with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, President Truman relieved the five-star general of his command for insubordination.

President Truman’s firing of General MacArthur, one of the great heroes of the Second World War, the man who accepted the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay on behalf of all Allied forces, caused a firestorm of criticism. When the general returned to the United States, he was fêted in New York with the largest ticker tape parade ever conducted in that city. He was greeted by enthusiastic admirers as he toured the country, accepting salutes and parades in his honor in a number of cities. In his farewell address to a joint session of the United States Congress, he gave a moving speech in which he claimed that, “In war there can be no substitute for victory.”

See MacArthur’s Farewell Address to Congress. See also William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880 - 1964 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1978), one of several biographies. MacArthur also wrote his own memoir, Reminiscences. An excellent 1977 film, MacArthur, starring Gregory Peck, was directed by Joseph Sargent.

President Truman replaced General MacArthur with General Matthew Ridgway, another World War II veteran, and General Ridgway soon began reclaiming some of the ground that had been lost following the Chinese invasion. But further attempts to push the war back to the Chinese border were not feasible, and the fighting degenerated into a stalemate around the 38th parallel. In the presidential election campaign of 1952, General Eisenhower, the Republican candidate, promised that if elected he would go to Korea and seek a solution to the conflict, a promise he fulfilled. Eventually a cease-fire was agreed upon and the fighting came to a desultory conclusion. That cease-fire, however, was not quite the same thing as peace, and tensions along the border between North and South Korea continued for many years. At the current time, American troops are still stationed in South Korea.

The American Experience in Vietnam

The Vietnam War has justifiably been called America’s longest war, even though the exact start date is difficult to determine; in any case, it was America's most frustrating war, and the first war America ever lost. The American Experience in Vietnam was a tragedy of great proportions, but dismissing the conflict as an aberration is a mistake. Many well-intentioned people thought they were doing the right thing in resisting Communist domination of Vietnam. Even given the fact that the excesses of Senator McCarthy and other zealots went too far, the majority of Americans felt that fighting international communism was a worthwhile goal.

The legacy of Vietnam is still cloudy, and some of the most penetrating works on the Vietnam War have come out in the past decade. Vietnam has also been called America’s first television war, where scenes from the battlefields were piped into our living-rooms night after night. Movies and television since the end of the war have, however, tended to warp our perceptions of that time, as scores of battle-fatigued, drug-addicted veterans have paraded across our screens.

The legacy of Vietnam is still cloudy, and some of the most penetrating works on the Vietnam War have come out in the past decade. Vietnam has also been called America’s first television war, where scenes from the battlefields were piped into our living-rooms night after night. Movies and television since the end of the war have, however, tended to warp our perceptions of that time, as scores of battle-fatigued, drug-addicted veterans have paraded across our screens.

One of the most important things to know about the American experience in Vietnam is that most Americans, including those who made decisions concerning America's involvement in the Vietnam War, knew very little about the history of Vietnam. The lesson from that unfortunate fact should be obvious: When American troops are committed to a foreign war, it is useful to have an understanding of the nation and its people before becoming engaged. American leaders understood Germany and Japan to some extent before the U.S. entered the war, but there can be little doubt that Pearl Harbor came as a shock. Similarly, we underestimated the likelihood that China would get into the Korean War. Both political and military leaders were mistaken. While wars may be deemed unavoidable, no matter how a decision to get into it is achieved, a first principle should always be: “Know your enemy!”

Vietnamese History. Vietnam was an old country when Columbus discovered America. According to legend, the history of Vietnam goes back centuries before the Christian era. In about the year 40 C.E. the first attempt was made to separate Vietnam from its Chinese roots, and although Vietnam became a separate country, ties between Vietnam and China remained very close—and often troubled—for centuries. In 1428 China recognized the independence of Vietnam, and although the country remained independent, it soon became divided between North and South. Continuing struggles against their Chinese and Cambodian neighbors kept the Vietnamese in a state of war for much of their modern history.

In the 1600s French missionaries visited Vietnam and began to spread French influence and the Christian faith among the Vietnamese people. Through the 1600s and 1700s the French government supported missionary efforts and propped up Vietnamese leaders who were friendly to the French. When Napoleon III became Emperor of the French, he exploited his connections with Vietnam as a backdoor to China, and absorbed Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia into a region which became known as French Indochina.

French colonial rule of Vietnam was harsh and exploitative, and early in the 20th century various nationalist movements among the Vietnamese challenged France's colonial rule. This nationalist resistance eventually fell under the leadership of a Vietnamese revolutionary named Nguyen Ai Quoc, or “Nguyen the Patriot,” who later changed his name to Ho Chi Minh.

Ho was born on May 19, 1890, son of a Confucian classics scholar and teacher, and he grew up with a love of learning. The young man continued to read and study and was soon sent off to study classics with a tutor who was strongly patriotic. Ho adopted not only his teacher’s patriotic attitudes, but also the humanitarian focus of classical Confucian writings; he began to write his own patriotic verse. As a teenager, his patriotic feelings were enhanced by his learning of the cruel treatment many Vietnamese suffered under their French rulers. At age seventeen he was admitted to the National Academy in Hue, having already adopted the idea that if he was to defeat the French, he would have to learn about their language and culture. He was also intrigued by the ideals of the French revolution—liberty, equality, fraternity—even though they were not practiced by the French in Vietnam.

Ho soon became active in anti-French protest activities and was eventually expelled from the Academy. He then began to think of traveling abroad to further his education. He soon signed on as a cook’s helper on a ship and spent much of the next two years at sea. His travels took him to many countries in Africa, Asia and Europe. Eventually his ship stopped in New York, and he decided to seek employment in the city and spent several months in the United States, where he observed social conditions of the working classes closely. The record of his travels is vague, but he apparently left the United States in 1913 or 1914 and lived for a time in Great Britain, where he continued to work and study. Still gravitating towards France, the oppressor of his people, Ho eventually made his way to Paris and was in the city as the Versailles Treaty was bringing a formal end to World War I.

Ho soon became active in anti-French protest activities and was eventually expelled from the Academy. He then began to think of traveling abroad to further his education. He soon signed on as a cook’s helper on a ship and spent much of the next two years at sea. His travels took him to many countries in Africa, Asia and Europe. Eventually his ship stopped in New York, and he decided to seek employment in the city and spent several months in the United States, where he observed social conditions of the working classes closely. The record of his travels is vague, but he apparently left the United States in 1913 or 1914 and lived for a time in Great Britain, where he continued to work and study. Still gravitating towards France, the oppressor of his people, Ho eventually made his way to Paris and was in the city as the Versailles Treaty was bringing a formal end to World War I.

In Paris Ho attracted attention for his anti-colonial activities. He drafted a petition demanding for political rights for the Vietnamese people based on Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points. He hand delivered it to major delegations and received a reply from Wilson’s advisor, Colonel House, that it would be shown to the President. An admirer of Wilson because his call for self-determination for all peoples, Ho was disappointed that he never received a reply from Wilson. Ho associated himself with other Vietnamese patriots in Paris, joined the French Communist Party and adopted the name of Nguyen Ai Quoc, or “Nguyen the Patriot.” As he became more deeply involved with Communist ideology he began to study the writings of Karl Marx intensely, especially Marx's anti-colonial ideas. He fell under steady surveillance by French authorities as he grew ever more active in anti-colonial movements. Next, still going by the pseudonym of Nguyen Ai Quoc, Ho left Paris for Moscow in 1923, where he hoped to observe Communism in action.

Disillusioned by the realities of Bolshevik Russia, Nguyen Ai Quoc nevertheless became involved with the Comintern. He took up studies at the Communist University of the East in Moscow and continued to be active in political affairs, becoming acquainted with many Communist leaders, including Lenin and future Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai. Having risen to a position of prominence in Moscow as a leading advocate of colonial reform, Ho nevertheless always intended to return to Asia. In 1924 he made his way to Canton, China, where he quickly became involved with Chinese Communist operations. He continued to work and travel and arrived in Hong Kong in 1930. There he founded the Vietnamese Communist Party.

Ho continued to monitor anti-colonial developments in Vietnam (which were not going well) and traveled widely in Asia over the next few years, helping to form Communist parties throughout the region. In 1934 he returned to Moscow and resumed his revolutionary work and studies and finally, in 1941, just as World War Two was breaking out in Asia, he returned to Vietnam. During the war he adopted the name Ho Chi Minh and began work on the process of ending French colonial rule and bringing Communism to all of Vietnam. This quest was interrupted when Vietnam was occupied by the Japanese, who proved to be harsh rulers. When the war ended, Ho and his Communist friends were confronted with the problem of trying to keep the French from reasserting their domination of Vietnam. Because of long-standing animosity between China and Vietnam, which had resulted in intermittent warfare over the centuries, Ho and his followers decided to compromise with the French to deter the Chinese from interfering in Vietnam, and the French returned to Vietnam.

Following World War II, the United States was plunged into the Cold War, and its crusade against Communism was focused mostly on Europe. President Truman’s assistance to Greece and Turkey, the Marshall plan, and the Berlin airlift were all anti-Communist initiatives aimed at Europe. Meanwhile, Mao Zedong took control of China in 1949, and the Korean War broke out in 1950, shifting America’s focus to Asia. At the same time the French found themselves in an intense struggle against the North Vietnamese Communists, who were led by Ho and his compatriot, General Vo Nguyen Giap. Giap’s Viet Minh defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, and French colonialism in Southeast Asia came to an end.

The French asked for American aid in their fight in Vietnam, but presidents Truman and Eisenhower were reluctant to get deeply involved. Following the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, negotiations in Geneva in 1954 led to the partitioning of Vietnam into North and South, the North being led by the Communists under Ho, the South by the Emperor Bao Dai and his hand-picked premier, Ngo Dinh Diem. Fearing that if all of Vietnam fell to communism, other nations in the region would soon follow under the so-called domino theory, President Eisenhower offered financial and limited military support to the Diem regime. During the late 1950s Diem managed to hold his own against the North Vietnamese Communists and their Southern allies, the Vietcong, but the struggle was intense.

America and Vietnam, 1961-1973

In President Kennedy's stirring inaugural address of January 20, 1961, he said:

“To those peoples in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required—not because the Communists are doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right.”

One can easily imagine that President Kennedy had Vietnam in mind as he spoke those words. Kennedy was, above all else, a cold warrior, and his clashes with Soviet Premier Khrushchev were unsettling to the world. Following a meeting with Khrushchev in Vienna, during which Premier Khrushchev verbally abused the young and, as Khrushchev saw him, vulnerable American president, Kennedy returned vowing to take a stand against Communism. He is reported to have said, “Now is the time, and Vietnam is the place.” At the time the United States had approximately 2,000 advisers in Vietnam.

Whether actual or apocryphal, Kennedy’s words were soon realized as the President sent billions of dollars in aid and increased the number of American advisers in Vietnam to 16,000. America's involvement in the war was deeper than was reported at the time, for many of the American advisers, who were supposedly operating only in an advisory role, were actually participating in combat operations. As American casualties, though few in number, began to be felt, it was clear that the American involvement in Vietnam was deepening.

The principle architect of President Kennedy’s Vietnam strategy was Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara, the former Ford Motor Company executive whose close assistants, known as the “whiz kids,” outlined plans based on systems analysis in the name of efficiency. Under McNamara’s guidance, substantial cost-reduction programs were instituted. The application of detailed analysis to a complex war situation in Vietnam, however, eventually proved less than successful. Secretary McNamara served Presidents Kennedy and Johnson; he was replaced late in President Johnson's second term.

The principle architect of President Kennedy’s Vietnam strategy was Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara, the former Ford Motor Company executive whose close assistants, known as the “whiz kids,” outlined plans based on systems analysis in the name of efficiency. Under McNamara’s guidance, substantial cost-reduction programs were instituted. The application of detailed analysis to a complex war situation in Vietnam, however, eventually proved less than successful. Secretary McNamara served Presidents Kennedy and Johnson; he was replaced late in President Johnson's second term.

The administration of Premier Diem, a Catholic, faced increasing difficulties, and he had trouble not only controlling the Communist insurgents, but he also faced rebellions from the Buddhist population, who felt they were being oppressed. A number of Buddhist monks set themselves on fire, and in response the Diem’s wife, Madame Nhu, (sometimes referred to by Americans as the “Dragon Lady”) crassly referred to the self-immolations as “Buddhist barbecues.”

By 1963 rebellion was in the air in Vietnam and a group of Vietnamese generals approached American Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. to express their dissatisfaction with Diem. Suggestions that a coup was being planned reached Washington in late August on a weekend when many of Kennedy’s advisers were vacationing. Partially as a result of faulty communications, Kennedy’s aides sent a telegram to Saigon giving apparent consent to a coup. No such decision had been reached by the Vietnamese generals, however. Nevertheless, believing that The U.S. government wanted Diem eliminated, and encouraged by Ambassador Lodge, the generals went ahead with the coup and in the process assassinated Premier Diem, an action which the Americans had neither foreseen nor approved. President Kennedy was shocked upon hearing of the assassination and accepted some responsibility of the misleading telegram that had been sent in August. The situation in Vietnam did not improve, however, and the country remained in political turmoil over the coming year as a succession of premiers moved through the nation’s highest office.

Diem’s assassination was followed a few weeks later by the assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas. Kennedy had recently stated that the war in Vietnam was Vietnam's to win or lose, that the United States could do nothing more than assist. Some historians feel that he had indicated his intentions to begin removing advisers and had planned to have the American military presence out of Vietnam by 1965. Much speculation about what might have occurred had Kennedy not been killed has, however, failed to reach any definite conclusions about the ultimate course of the war; we can only assume that the path would have been different, perhaps very different.

When Vice President Lyndon Johnson assumed the presidency, he inherited the situation in Vietnam, which pleased him little. He had in mind the creation of what he later called his “Great Society,” which was meant to be an all out assault on poverty, ignorance, racial discrimination and other American social ills. The situation in Vietnam following Diem’s assassination continued to deteriorate, however, and President Johnson did not make any major changes to President Kennedy’s Vietnam policy. In August 1964 an attack by North Vietnamese gunboats on two United States destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin was reported. The destroyers U.S.S. Maddox and U.S.S. Turner Joy both reported being attacked by North Vietnamese gunboats. While the Maddox may have been attacked, the Turner Joy was not. No damage or injuries occurred on either vessel. In response, Congress passed the Tonkin Resolution. It authorized President Johnson to do whatever was necessary for success in Vietnam. (See Tonkin Resolution.)

Escalation. President Johnson kept the Gulf of Tonkin resolution “in his pocket” until after his overwhelming landslide victory in 1964. Even after the election, however, he did little about Vietnam for about a month, but in early 1965, following an attack on an American special forces camp near Pleiku that killed 18 Americans, President Johnson decided to up the ante. He sent two battalions of Marines to Danang to guard the airfield, from which American planes began the bombing of North Vietnam in an operation called “Rolling Thunder.” Marine Commandant General Wallace Green argued that Marines were not comfortable with a passive, defensive role and recommended search-and-destroy missions. As the Marines in the field found themselves facing a resolute enemy, Johnson followed up with army units to guard the air base, more Marines and additional air power, thus beginning a process known as escalation. The number of Americans in Vietnam grew rapidly, so that by 1966 about half a million American soldiers, Marines, sailors and airmen were fighting in Vietnam.

The war was as nasty a conflict as has ever been fought by Americans. Alongside regular North Vietnamese units, who were well-trained, determined and supported by Russian and Chinese arms and equipment, the Communist insurgents in the south, the Vietcong, added to  the burdens of the American military by harassing both American and South Vietnamese units. Ambushes, rocket and mortar attacks and assassinations of political officials were all part of the Viet Cong arsenal. Although the United States military understood that the war in Vietnam was an irregular war, the military leadership never quite grasped the true nature of the conflict. Much high-tech military equipment was tested and used in Vietnam, often, however, to little advantage.

the burdens of the American military by harassing both American and South Vietnamese units. Ambushes, rocket and mortar attacks and assassinations of political officials were all part of the Viet Cong arsenal. Although the United States military understood that the war in Vietnam was an irregular war, the military leadership never quite grasped the true nature of the conflict. Much high-tech military equipment was tested and used in Vietnam, often, however, to little advantage.

In 1965 an American army unit, the 1st Battalion of the 7th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), tangled for the first time with a full blown North Vietnamese regular army unit in the Ia Drang Valley, near Pleiku. Elements of North Vietnamese divisions numbering approximately 2,000 soldiers were in position as helicopters landed Lt. Colonel Hal Moore’s battalion, which had a strength of about 450 men.

The concept of airmobile infantry, with ground troops transported by helicopters into remote combat areas, was to get a severe test as the battalion lost 234 dead and 242 wounded, while North Vietnamese casualties were numbered at well over 1,000 killed and wounded. Both sides learned a great deal about the capabilities of their enemy, significant lessons, as they were to face each other again and again in the ensuing years.

The full story is told in a book by Lieutenant General Harold G. Moore and Joseph L. Galloway, We Were Soldiers Once...and Young: Ia Drang - the Battle That Changed the War (New York: Random House, 1992.) An excellent film, We Were Soldiers, based on the book by Hal Moore and reporter Joe Galloway, who was with the battalion during the battle, starred Mel Gibson as Colonel Moore in the battle of Ia Drang.

The major difficulty for American forces in Vietnam was that most of the enemy that they faced were not regular units that could be fought with conventional military tactics. Instead small bands of guerrillas, often hidden among the civilian population, fought by unconventional methods that did not respond well to conventional military tactics. There was no territory to be conquered, or lines to be broken through. Instead the years of fighting in Vietnam consisted of a series of operations that attempted to clear the Viet Cong and their North Vietnamese allies out of populated areas of the South. It was a frustrating, nerve-racking task, and it often fell short of goals because of conflicts between American and Vietnamese units over tactical decisions, and micromanagement of the war from Washington by people who little understood the Vietnamese landscape or culture.

A second film about Vietnam, Bright Shining Lie, starred Bill Paxton as Colonel John Paul Vann. Although substantially abridged from the book by Neil Sheehan, the film nevertheless covers much of the spectrum of what went wrong in Vietnam.

Out of frustration at what he saw as North Vietnamese intransigence, President Johnson tried to bring Ho and his followers to the bargaining table through continued bombing attacks against points in the North. The bombing, which was not very effective against disbursed North Vietnamese industry, did little except stiffen North Vietnamese determination to drive out the Americans. Meanwhile more and more American troops were sent to Vietnam and American strength in that country eventually reached over 550,000 soldiers, Marines and airmen. The writings of Ho and Giap from the period indicate that the Communists were willing to make whatever sacrifices were necessary to defeat the Americans, whom they assumed not to have the staying power to carry on the fight to a satisfactory end. Having worn down the French, the Vietnamese communists were confident that they could wear down the Americans.

The 1968 Tet Offensive. Following more than two full years of search-and-destroy operations stretching throughout the Vietnamese countryside, the American military found itself no closer to victory than when the first Marine battalions landed in 1965. Although military officials continued to claim that progress was being made in the war, those claims were apparently blasted during the Tet offensive of 1968, when the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese rose up across the countryside and attacked many major cities, including Saigon. Although the Communist Tet offensive was ultimately unsuccessful, scenes of the fighting in Saigon, even around United States Embassy, helped convince the American people that the Vietnam War was unwinnable. University students, activated by the war and by other social issues such as problems of integration and segregation in the South and a general discontent with conditions in American society, poured from campuses into the streets to protest the war in particular and American policies in general.

As United States casualties continued to mount, President Johnson decided in March 1968 that he would not stand for reelection, which came as a shock, not only for the nation, but even to his closest advisers and family. That brought to the forefront the Republican challenger Richard M. Nixon, whose political career had seemed to be at an end when he lost both the presidency to John F. Kennedy in 1960 and the governorship of California in 1962. But Nixon gained the nomination and ran against a fractured Democratic Party led by incumbent Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. Nixon claimed during the campaign that he had a secret plan to end the Vietnam War, and that plan turned out to be what he called “Vietnamization”; namely, he turned the war more and more over to the control of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and its political leaders.

As United States casualties continued to mount, President Johnson decided in March 1968 that he would not stand for reelection, which came as a shock, not only for the nation, but even to his closest advisers and family. That brought to the forefront the Republican challenger Richard M. Nixon, whose political career had seemed to be at an end when he lost both the presidency to John F. Kennedy in 1960 and the governorship of California in 1962. But Nixon gained the nomination and ran against a fractured Democratic Party led by incumbent Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. Nixon claimed during the campaign that he had a secret plan to end the Vietnam War, and that plan turned out to be what he called “Vietnamization”; namely, he turned the war more and more over to the control of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and its political leaders.

Along with his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, President Nixon pressured the North Vietnamese to enter negotiations to end the war, hoping that by alternately increasing and decreasing military force, he could bring the North Vietnamese at the bargaining table to conclude a successful end of America’s involvement in the war. After four years and thousands more casualties on both sides, the Paris peace accords were finally signed, bringing what President Nixon called “peace with honor.” American troops had been leaving Vietnam gradually for two years when the accords were finally signed. Along with the signing and the final withdrawal of American troops, the return of the American prisoners of war from the camps in Hanoi signaled the end of America’s military participation in Vietnam.

American advisers, along with financial and military support continued in Vietnam, however, until the Communist offensive of 1975. In a matter of a few short weeks in that year, the North Vietnamese quickly overran the South Vietnamese army. As North Vietnamese tanks rumbled into Saigon, soon to be renamed Ho Chi Minh City, the last Americans and their Vietnamese collaborators fled the country by plane, helicopter and even by small boats. Thus came the ignominious end of the American experience in Vietnam, which had resulted in 58,000 American casualties, millions of Vietnamese casualties and extensive property damage throughout the country. Not only that, but the Communists now controlled all of Vietnam, and thus America had lost its first war.

The Vietnam War left scars in America that have been a long time in healing, and as the presidential campaign of 2004 made clear, those wounds can easily be reopened. Thousands of soldiers suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, and many still bear the wounds they received in Vietnam. The financial cost of the war hurt the American economy, and the wide ranging dissent and military failure undermined the country's confidence in its leaders and its ability to guide the world towards the path of international peace. The final legacy of America's involvement in Vietnam has yet to be written.

See “A Vietnam Village,” a true story. | Chronology of Vietnam War & Vietnamese History